Saharan Halophytic

The ecoregion’s land area is provided in units of 1,000 hectares. The conservation target is the Global Safety Net (GSN1) area for the given ecoregion. The protection level indicates the percentage of the GSN goal that is currently protected on a scale of 0-10. N/A means data is not available at this time.

Bioregion: Northern Sahara Deserts, Savannas & Marshes (PA24)

Realm: Southern Eurasia

Ecoregion Size (1000 ha):

5,403

Ecoregion ID:

745

Conservation Target:

73%

Protection Level:

3

States: Egypt, Algeria, Tunisia, Mauritania, Libya, Western Sahara

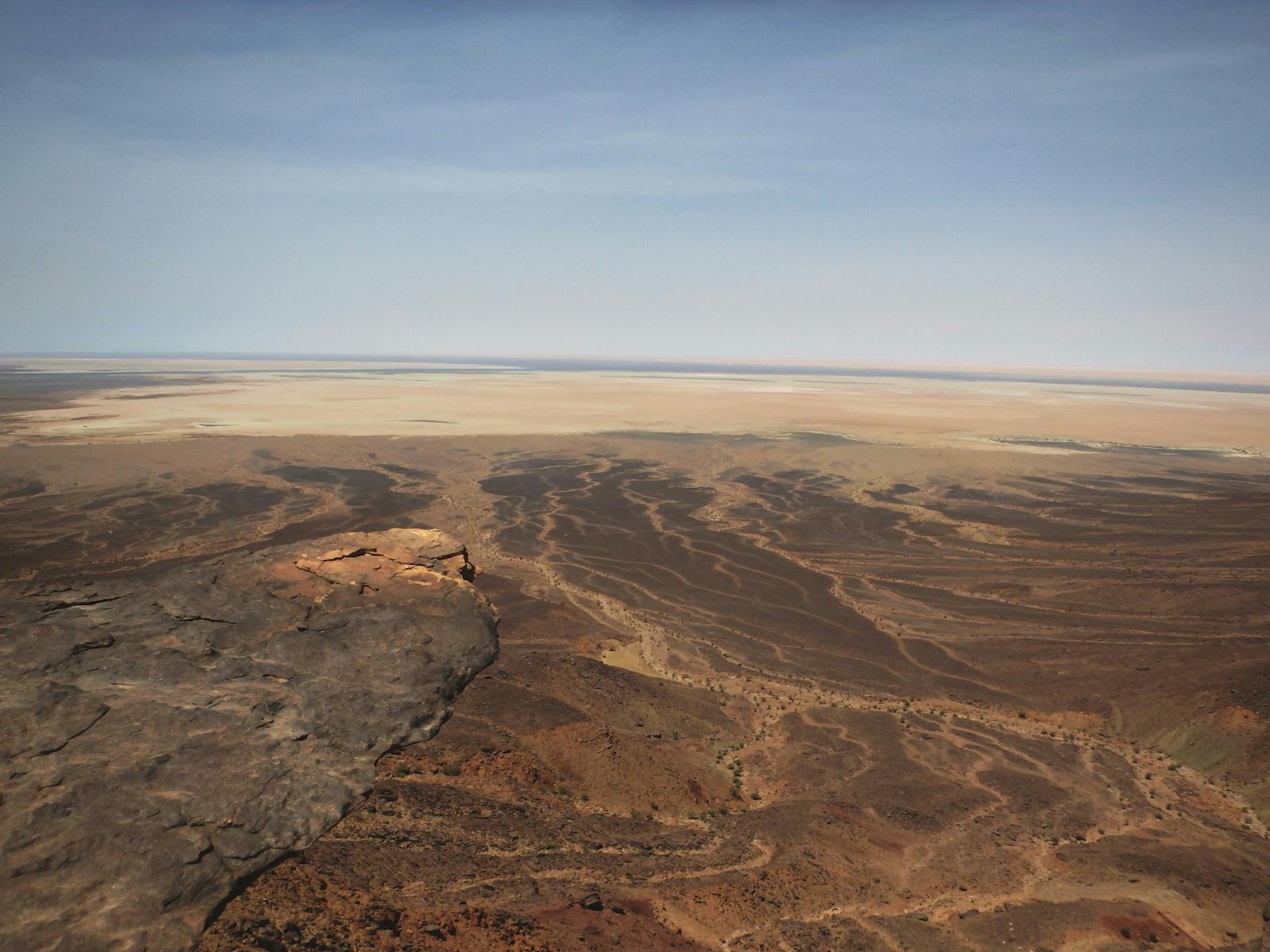

Saline depressions are sunken landforms that often host a unique, salt-tolerate type of vegetation called halophytes. These areas also contain freshwater oases within a hyper-arid region. They are particularly important to a diverse population of animals and plants, including rodents and grazing camels, during dry seasons. Scattered across the northern Saharan desert, such as the Qattara depression at 120 m below sea level, these depressions are also known as chotts (shallow, irregularly flooded depressions) and sebkhas (irregularly flooded depressions).

The flagship species of the Saharan Halophytic ecoregion is the Dorcas gazelle. Photo | Michael Erenburg, Dreamstime

The Saharan Halophytics cover a number of saline depressions scattered across northern Africa. The most extensive areas from west to east are Iriki and Oued Draa in Morocco; Rhir Valley, Sebkhat Tidikelet, Sebkha of Timimoun, Chott Hodna, and Chott Melghir in Algeria; and the Chott el Gharsa (600 km2), Chott Djerid (4,600 km2), and Chott Fedjedj (800 km2) in Tunisia. The Qattara Depression and the Siwa Depression in Egypt are two of the most important depressions in the ecoregion.

The Qattara Depression is 285 km long and 135 km wide and covers approximately 19,500 km2 of land below sea level. Salt marshes occupy approximately 300 km2, with some areas having encroaching wind-blown sands. The Siwa Depression extends east-west over 82 km and is up to 28 km wide. This depression has 18 lakes covering approximately 7 km2 with a maximum depth of 25 m below sea level. Each lake is surrounded by brackish marshlands.

All of the lakes are saline but are supplied with fresh water from 18 underground springs, for example, the Nubian sandstone aquifer, which is the largest known fossil water aquifer system in the eastern Saharan desert. Temperatures reach 50°C in the summer and drop below 0°C during the nights in winter. Rainfall is irregular, varying between 10 and 100 mm per year. Here, evaporation from surface water and groundwater exceeds rainfall at close to 3000 mm per annum, leading to the deposition of soluble salts to form saline soils or solonchaks.

Red-rumped wheatear. Image credit: Francesco Veronesi, Creative Commons

The vegetation of the ecoregion belongs to the ‘azonal halophytic vegetation' and includes halophytic (salt-loving) species. These halophytic habitats contain low species richness, with most species showing Palearctic and Afrotropical affinities. Among the small mammals, gerbils (e.g., North African and Baluchistan) are the most abundant species, followed by sand rats (fat sand rat and lesser sand rat), jerboas (lesser Egyptian jerboa and greater Egyptian jerboa), and jirds (Mzab Gundi jird and Sundevall’s jird).

Predators in the ecoregion include Rüppel's fox and Libyan striped weasel. Desert antelopes may still be found in small numbers, such as the slender-horned gazelle, dama gazelle, Dorcas gazelle, and the red-fronted gazelle.

A number of desert-adapted birds also occur, such as the thick-billed lark, the desert wheatear, and the red-rumped wheatear. A greater diversity of birds can be found in the wetland areas, particularly for wintering and migrant Palearctic waders, waterfowl, red-rumped, and birds of prey, especially when they are flooded. In the Siwa Depression, some of the species include the lesser flamingo and greater flamingo that nest in the area. Reptile diversity is relatively high and includes the Egyptian fringe-fingered lizard, eyed skink, and the desert monitor.

In Egypt, the protected areas include the Siwa multiple-use management area and the El-Qattara depression. In Tunisia, Chott Jrid, Sebkhat Sidi El Henim, and Sebkhat Kelbia are designated as Ramsar wetlands of international importance. Other than these protected areas, there is no other formal protection of the ecoregion.

_-CC-_Shantanu_Kuveskar-2020.jpg)

Desert wheatear. Image credit: Shantanu Kuveskar, Creative Commons

A major threat to the Qattara Depression is the proposal of hydro projects which aim to flood the depression with seawater to make an inland sea and, in the process, generate hydropower. This will devastatingly impact the whole area by destroying existing natural habitats, contaminating non-renewable fossil groundwater which is used to irrigate arable land, increasing seismic activity, and changing the atmospheric moisture regime.

An additional major threat is the continued process of desertification of the area (now exacerbated by climate change), which might result in the complete loss of wetland habitats and their replacement by salt flats and sand areas. In areas of the ecoregion that support permanent water sources, like the Siwa Depression, larger mammals have been hunted out.

The priority conservation actions for the next decade will be to 1) encourage and promote the uptake of drought-resistant plants to replace crops, including herbs for medicinal teas and cosmetics; 2) increase the oases-protected area network; and 3) develop community watershed management plans.

-

-

1. Burgess, N., Hales, J.A., Underwood, E., Dinerstein, E., Olson, D., Itoua, I., Schipper, J., Ricketts, T. and Newman, K. 2004. Terrestrial ecoregions of Africa and Madagascar: a conservation assessment. Island Press.

2. Powell, O. and Fensham, R. 2016. The history and fate of the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer springs in the oasis depressions of the Western Desert, Egypt. Hydrogeology journal. 24(2), pp.395-406.

3. Hereher, M.E. 2015. Capacity assessment of the Qattara Depression: Egypt as a sink for the global sea level rise. Geocarto International. 30(2), pp.123-131.

4. Zahoran, M.A. and Willis, A.J. 1992. The vegetation of Egypt. London: Chapman and Hall -

Cite this page: Saharan Halophytic. Ecoregion Snapshots: Descriptive Abstracts of the Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World, 2021. Developed by One Earth and RESOLVE. https://www.oneearth.org/ecoregions/saharan-halophytic/

-

.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&w=300)