South Arabian Plains and Plateau Desert

The ecoregion’s land area is provided in units of 1,000 hectares. The conservation target is the Global Safety Net (GSN1) area for the given ecoregion. The protection level indicates the percentage of the GSN goal that is currently protected on a scale of 0-10. N/A means data is not available at this time.

Bioregion: Red Sea, Arabian Deserts & Salt Marshes (PA26)

Realm: Southern Eurasia

Ecoregion Size (1000 ha):

37,328

Ecoregion ID:

840

Conservation Target:

43%

Protection Level:

0

States: Oman, Yemen, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia

Vast desert plateaus riddled with a network of wadis and dotted with hardy Acacia trees characterise this ecoregion. Nubian ibex traverse the same slopes where frankincense trees grow, the much-coveted resin from which has been traded along the incense route for thousands of years. Implementation of strict protections in the region will be essential to combat degradation of the land from oil drilling and overgrazing, ensuring the survival of the rich desert ecosystems found here.

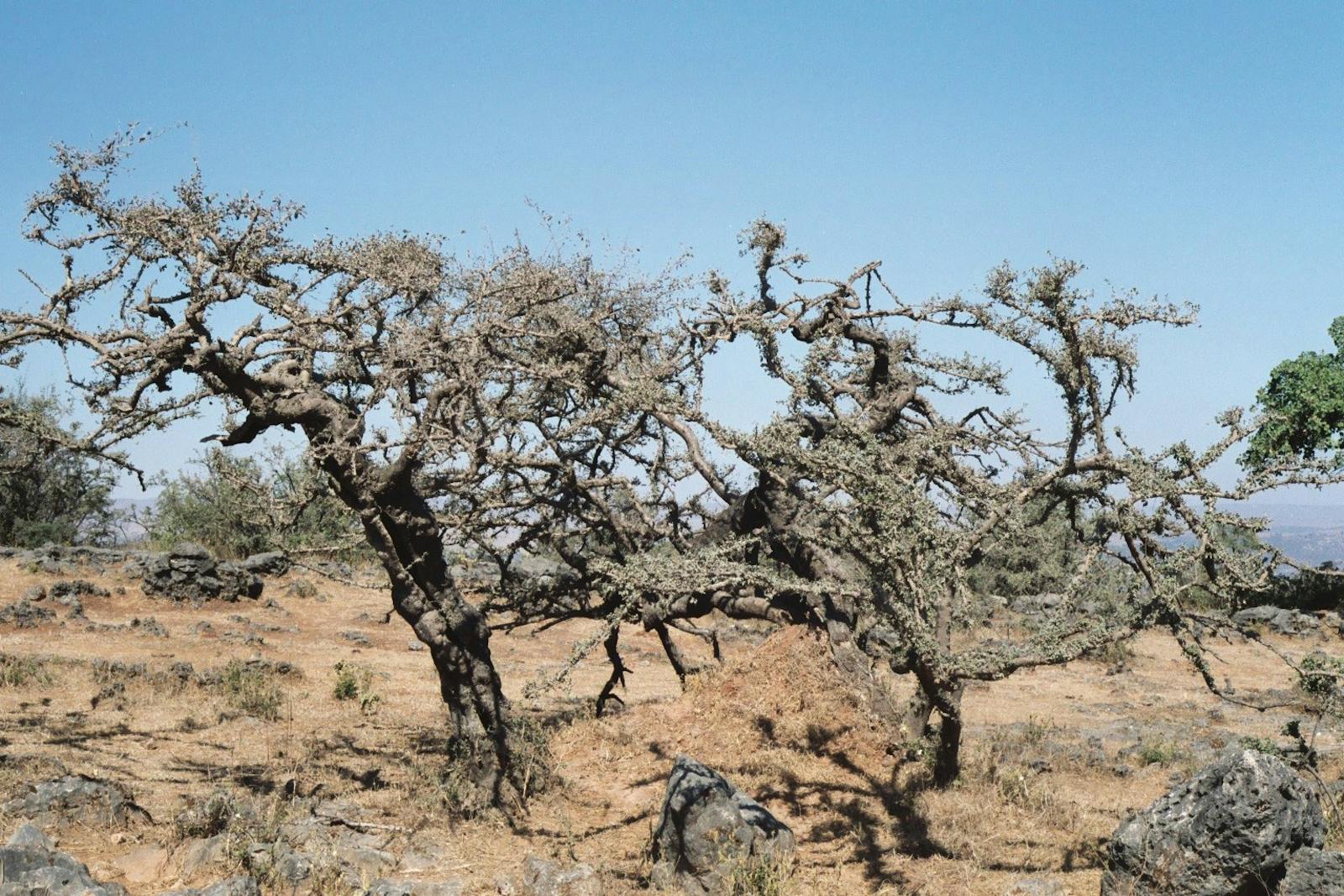

The flagship species of the South Arabian Plains and Plateau Desert ecoregion is the Frankincense tree. Image credit: Creative Commons

This ecoregion largely lies within Oman and Yemen, although it includes a small section in the United Arab Emirates in the East. It encompasses the vast Hadramaut plateau in Yemen, as well as the Jiddat al Harrasis plateau in Central Oman, which boasts one of Earth’s most impressive collections of lunar meteorites. The desert plains running east from Jiddat towards the foothills of the Hajar mountains are also included. A complex network of valleys or wadis incise the plateaus.

The climate is hot and arid; summer months may see temperatures of up to 47°C in some areas of Oman, dropping to around 25°C in the cooler months. Temperatures in Yemen are slightly lower. Average rainfall is typically less than 50 mm, although winds bringing moisture from the Arabian sea to the eastern Jiddat al Harrasis area means vegetation is relatively well-established there.

Arabian leopard. Image credit: Creative Commons

Acacia is the dominant vegetation across much of the ecoregion, existing alongside typical shrubs such as Convolvulus oppositifolia and sedge, with open, relict woodlands of ghaf present in sandy wadi channels. Oman’s central desert is a local center of plant endemism, with an estimated 35% of the species being endemic.

A ground cover of several grass species across the region, of which Stipagrostis sokotrana is dominant, is especially noticeable after periods of rainfall. The western Omani desert typically lacks trees, with species such as Zygophyllum spp. and Haloxylon salicornicum most common. In interior Dhofar and the eastern Mahra Boswellia sacra, Oman’s national tree and the source of frankincense, can be found. This aromatic resin has been traded on the peninsula for thousands of years and was once worth more than its weight in gold.

Nubian ibex. Image credit: Creative Commons

Caracals, Arabian wolves, honey badgers, Nubian ibexes, and sand gazelles are found across the ecoregion, as is the majestic Arabian oryx, which was re-introduced to Oman’s Al Wusta region in the 1980s after its extinction in the wild. A small area of the Jabal Samhan Nature Reserve on the Omani coast lies within this ecoregion, where the elusive Arabian leopard has been sighted.

The desert is also home to the endemic Omani spiny-tailed lizard and Dipcadi biflora, as well as a diverse array of desert breeding birds such as the spotted thick-knee, and crowned sand grouse. The small island of Masirah just off the Omani coast is an important site for migrating and wintering birds in the Middle East, also hosting an endemic subspecies of the Cape hare and one of the world’s largest nesting aggregations of the loggerhead turtle.

Loggerhead turtle. Image credit: Katie Johnson, Creative Commons

Groups of nomadic pastoralists live across the ecoregion. Larger settlements are dotted along the coast, as well as in the densely populated Hadramaut region of Yemen, where distinctive, UNESCO-recognized mudbrick high-rises emerge from the gravel plains. In addition to traditional land uses such as grazing sheep and cutting of vegetation for firewood, the deserts in both Oman and Yemen have become popular sites for oil extraction.

There is little protective legislation covering this area: there are no protected areas in the Yemeni section of the ecoregion, and the Omani government reduced the size of the Oryx reserve in Al Wusta by 90% in 2007 in order to conduct oil explorations. This led to the removal of World Heritage Site status by UNESCO in the same year. The Frankincense Park of Wadi Dawkah, an element of the ‘Land of Frankincense’ UNESCO World Heritage site near the Dhofar coast, remains.

Caracal. Image credit: Creative Commons

Overgrazing has drastically modified the landscape and there are concerns about the effect of this reduced vegetation cover on the resilience of the ecosystems to future climate change and predicted increases in drought frequency. Native fauna are threatened by overhunting, with fragmentation of the land for urban developments, harvesting of soil, and oil drilling reducing the viability of what small populations remain. In some wadis, pumping water from shallow aquifers and building in the valleys has led to the drying of outflows with devastating consequences for the vegetation dependent upon this water.

Arabian wolf. Image credit: Ahmad Qarmish, Creative Commons

Priority conservation actions over the next decade will be to: 1) significantly increase the protected area network across the region; 2) conduct research into the effect of climate change on flora and fauna in the region; and 3) implement restoration programs for already-degraded habitats.

Citations:

- Ghazanfar, S. (2004). ‘Biology of the central desert of Oman’. Turkish Journal of Botany. 28. pp.65-71.

- Aljahdhami, M. et al. (2011). The reintroduction of Arabian oryx to the Al Wusta. Wildlife Reserve, Oman: 30 years on. From IUCN: Global Reintroduction Perspectives, 2011.

- BirdLife International (2019) ‘Important Bird Areas factsheet: Jiddat al Harasis’. [Online]. Available from: http://www.birdlife.org [Accessed 09/08/2019]

.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&w=300)