Finding a refuge for corals amid decimated reefs in the Galápagos

The Galápagos Islands are not widely known for their coral reefs. Most visitors to the islands’ waters seek big charismatic residents like sharks, manta rays, sea lions and whales, or unique creatures like marine iguanas. Dive shops in the Galápagos almost exclusively advertise the opportunity to see these large creatures, while few mention corals. Yet the archipelago is home to vibrant reefs, and we commenced the global Reefscape project there.

Perhaps so little is mentioned about reefs in the Galápagos today because of a history of coral bleaching across the archipelago. The scientific literature reports ocean temperature spikes of up to 4 degrees Celsius (7.2 degrees Fahrenheit) during the 1982-83 and 1997-98 El Niño events, and again to a much lesser degree in 2015. El Niño’s hot waters pushed many corals beyond their thermal tolerances, resulting in widespread reef-scale bleaching.

Reef off Darwin and Wolf Islands, northwest Galápagos.

Photo by Greg Asner / DivePhoto.org.

Coral, which is an animal, has a symbiotic relationship with algae. Known as zooxanthellae, these algae live within the coral’s exposed polyp tissues and are a crucially important photosynthetic source of carbon for the host. Bleaching refers to when coral, which has a naturally white underlying structure comprised of calcium carbonate, loses its more colorful symbiotic algae. Bleaching does not necessarily spell death for coral: If the hot-water event passes quickly, the coral will reunite with its algal partner, regain its color and avoid starvation. If, however, ocean warming events are extreme, persist for a long time or occur frequently, then corals die, sometimes resulting in the devastation of vast expanses of reef. While El Niño has brought coral-killing hot water to the Galápagos on a periodic basis for millennia, new research suggests that the frequency and intensity of warm ocean conditions may be increasing (Hughes et al. 2018).

The 1982-83 El Niño reportedly wiped out more than 90 percent of all shallow-water corals in the Galápagos — that is, corals living within about 20 meters (66 feet) of the ocean surface. That event was followed by another in 1997-98, and yet another in 2015. The ecological impacts of repeated ocean warming remain poorly understood in the Galápagos, as they do for many of the world’s coral reefs. The geography of bleaching, recovery and resistance to warming water is virtually unknown because monitoring is very limited.

In December 2017, we visited the Galápagos to survey coral reefs and to gather ecological information on their extent and condition. We also interviewed dive-industry professionals and scientists who witnessed the effects of El Niño and coastal development on the reefs. We focused on the current health of coral species and we surveyed total coral cover, an overall indicator of reef condition.

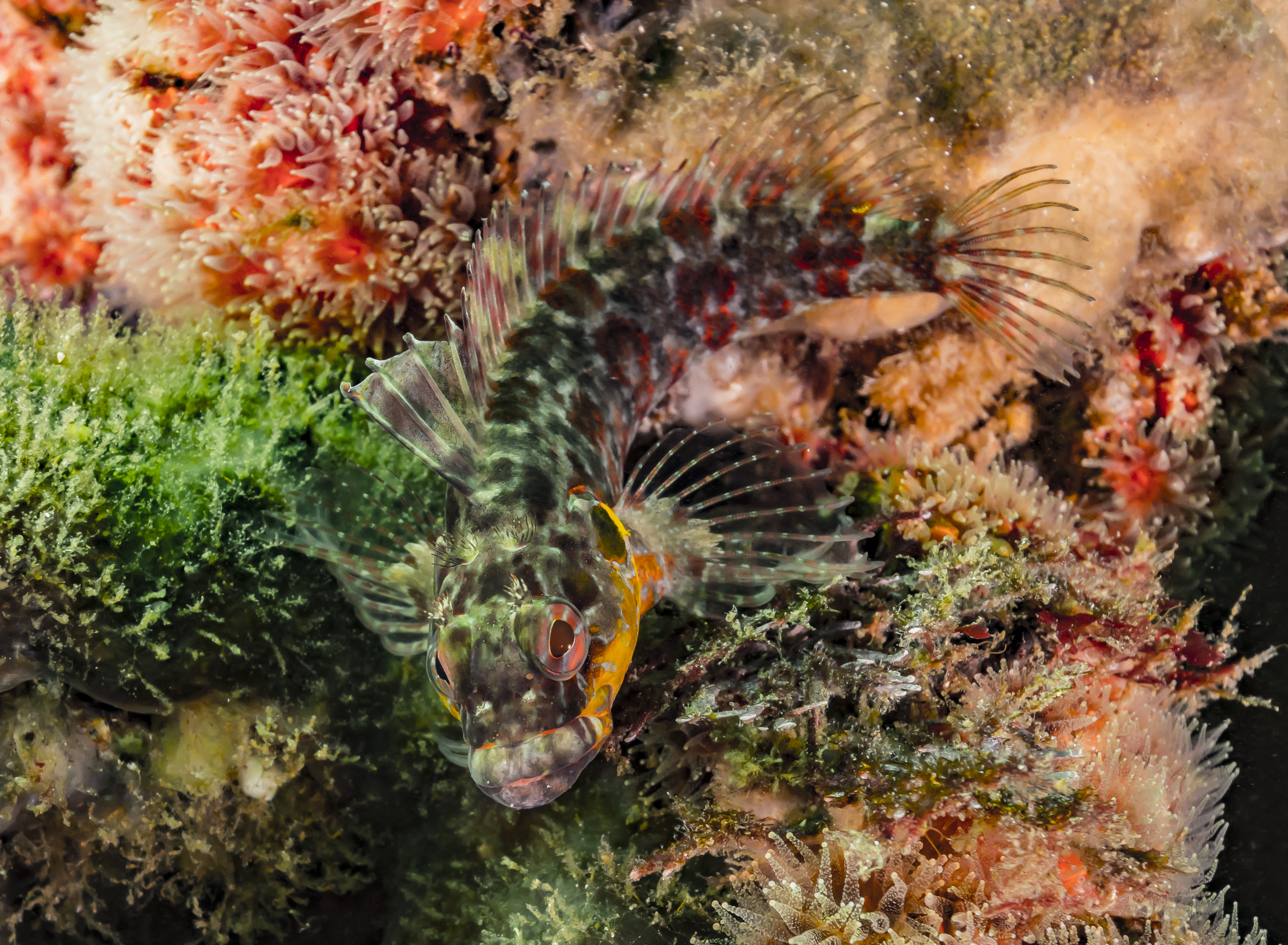

Reefscape off Darwin and Wolf Islands, northwest Galápagos.

Photo by Greg Asner / DivePhoto.org.

Starting on Santa Cruz, the most inhabited island in the Galápagos, we joined a dive operation to observe shallow reefs along the shoreline. We found very little coral cover, around 1 to 3 percent, which our hosts described as deeply diminished compared to “the old days”. Yet they didn’t just blame El Niño, but also increasing coastal pollution and fishing.

Like most oceanic islands, the Galápagos have a history of increasing fishing pressure dating back to European whalers, and culminating in recent news of the Ecuadorian government seizing a Chinese fishing vessel with more than 6,000 sharks taken from protected waters around the islands. In addition to large-scale commercial fishing, local communities have also impacted the reefs of the Galápagos. One dive-industry professional told his story of decades of coastal fishing, including years of highly damaging activities like using marine mammals such as sea lions for bait. His story is not unique, and although he gave up such fishing practices more than 20 years ago to become an underwater guide, he thinks illegal fishing is commonplace. The islands have a growing population and too few jobs.

Fish in the northwest Galápagos.

Photo by Greg Asner / DivePhoto.org.

Scientific research from around the world has repeatedly highlighted negative impacts of reef-fish removal on coral cover and condition. On Santa Cruz Island, we interviewed a prominent marine biologist whose work demonstrates that the removal of herbivorous reef fish allows for the spread of algae that inhibits coral growth. Low coral cover near Santa Cruz may be related to fishing as much as it is to El Niño.

Next, we traveled to San Cristóbal, joining dive professionals to survey a reef off a remote part of the island, and again we found just 1 to 3 percent coral cover, despite no signs of coastal development. One scientist told us that our observations off San Cristóbal are what he expected, given the severity of El Niño events over the past three decades. The coral we did see was arrayed in a seemingly helter-skelter pattern, and we never saw a coral colony greater than a few feet in diameter. The experience reaffirmed the idea that tracking changes in corals at a reefscape scale requires huge and spatially detailed monitoring areas. Today, however, scientists cannot easily monitor coral health at regional to global scales.

Santa Cruz and San Cristóbal are on the eastern side of the Galápagos archipelago, bathed in the cool Humboldt current. To compare these with eastern conditions, we visited the very remote reefs of Darwin and Wolf islands to the extreme northwest. They are far enough north to lie in the path of the much warmer Panama current flowing into the region from the northeast. As with the other islands, the Darwin and Wolf reefs reportedly underwent widespread bleaching in the 1982-83 El Niño. Yet scientists recently reported coral recovery in this northwestern region, and we too found massive coral colonies, some reaching 4.5 meters (15 feet) in diameter and covering well over 50 percent of the seafloor. Some areas we surveyed had more than 80 percent live coral cover.

Hammerhead shark, northwest Galápagos.

Photo by Greg Asner / DivePhoto.org.

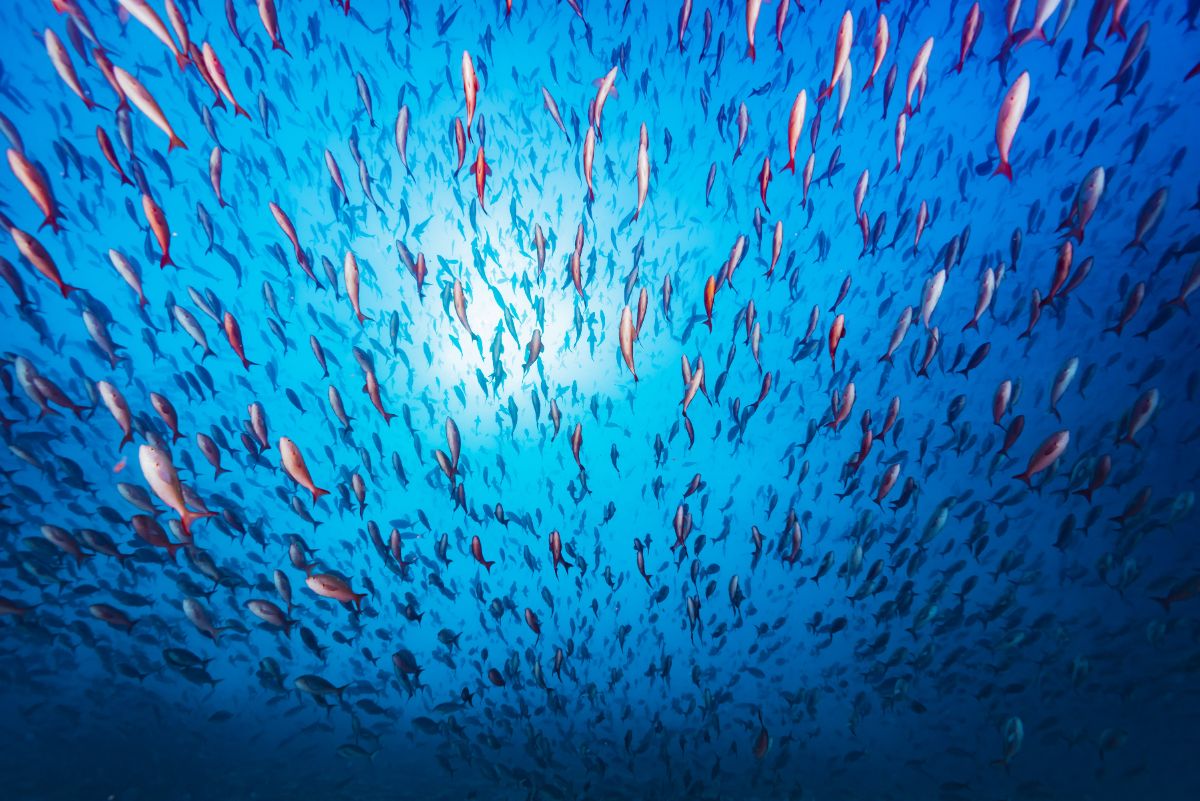

There were more positive impressions from the Darwin and Wolf reefs: We observed enormous schools of reef fish, including critically important herbivores that help maintain coral cover by consuming fast-growing algae. From herbivores to apex predators, such as the big schools of charismatic hammerheads and scores of moray eels, the entire ecosystem stood out as a refuge from the pervasive negative news about coral reef bleaching in the Galápagos. The abundance of life on these outer islands supports the emerging idea that there will be refugia of coral survival and recovery dotting the planet as we face an increasingly difficult ocean climate for reef ecosystems.

Our work in the Galápagos yielded three salient findings that we hope to explore in subsequent stops along the global Reefscape survey. First, although warm ocean events such as El Niño can wipe out vast areas of reef, coral survival and regrowth is evident, and recovery time truly matters. Scientifically, however, we know little about these processes and their geographic distributions. Second, our direct actions, be they destructive overfishing or constructive fisheries management, have a huge impact on the future of coral reef ecosystems. Third, one size does not fit all when it comes to coral reefs — even an archipelago hammered by coral-killing warm waters can harbor amazing refugia. We need to find them, champion their protection and include them in our global effort to conserve coral reefs into the future.

School of barracuda, northwest Galápagos.

Photo by Greg Asner / DivePhoto.org.

School of hammerhead sharks, northwest Galápagos.

Photo by Greg Asner / DivePhoto.org.

Reefscape in the northwest Galápagos.

Photo by Greg Asner / DivePhoto.org.

School of fish, northwest Galápagos.

Photo by Greg Asner / DivePhoto.org.

Reef shark, northwest Galápagos.

Photo by Greg Asner / DivePhoto.org.

Marinescape in the northwest Galápagos.

Photo by Greg Asner / DivePhoto.org.

Moray eel, northwest Galápagos.

Photo by Greg Asner / DivePhoto.org.

This article originally appeared on Mongabay.org.