Fish poop to the rescue

“I’m obsessed with waste,” says Marissa Cuevas Flores, a scientist from Mexico City. “We buy stuff, we use stuff, we throw it away. But there’s really no ‘away’.”

The 31-year old engineer sees waste everywhere. “Look around, wherever you are. Everything you see is going to become waste sooner or later. So what is going to become of all this stuff? Figuring that out — that’s my passion.”

That passion manifests in a circular-economy mindset that turns waste into solutions. Previously, for example, she launched a startup called Kitcel, which transformed styrofoam into wood varnish.

Now, Cuevas’ focus is on fish poop.

Her new venture, microTERRA, is a women-led team of scientists in Mexico, looking to use fish poop as a solution to help make a dent in world hunger, save water, and ease pollution.

microTERRA's on-site water-treatment system.

Photo credit: microTERRA

The proof-of-concept lab work is being done far from the sea — in Guanajuato, smack in the middle of north-central Mexico, equidistant from the Pacific and the Gulf of Mexico. The fish at the center of this effort in question, though, is not an ocean-dwelling creature, but rather the fresh-water tilapia.

Fish farming, also known as aquaculture, has grown significantly in Mexico, producing almost 400,000 tons of seafood annually, responsible for almost half a percent of the country’s GDP. But there are many aquaculture challenges — including environmental hazards.

“Aquaculture farmers have two main problems,” notes Cuevas. “High fish-feed costs — over 60% of their costs go solely into feeding the fish. And large amounts of waste water — every day, 30% of the water in the fish tanks needs to be replaced, which is also a drain on fresh water sources.

“We address these two main pain points,” she notes. “We can save up to 75% of the fresh water that a fish farmer uses, and we can cover 40% of their fish-feed demands.”

Even more importantly, she notes, is stopping downstream pollution of waste water.

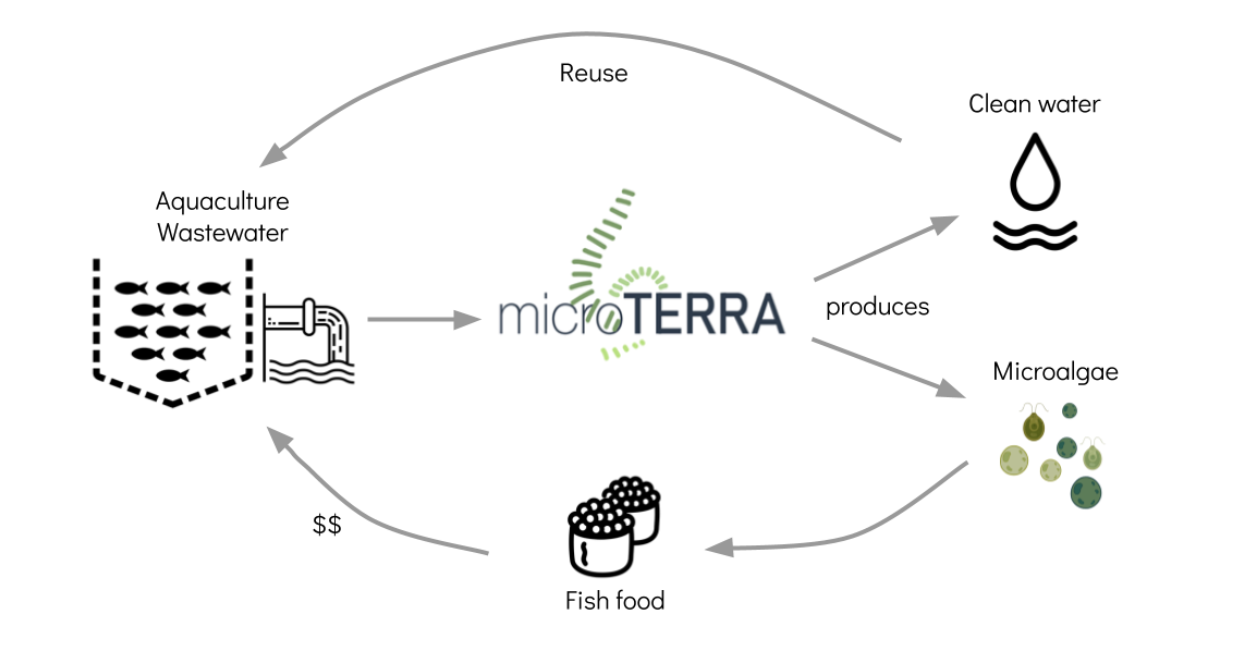

So what does microTERRA actually do? It develops on-site water-treatment systems that use micro-algae to transform wastewater into a sustainable protein source for the tilapia while cleaning the water. In essence, it turns fish poop into fish food, which requires less changing of water, and thus produces less waste water.

microTERRA's circular economy diagram

Photo credit: microTerra

There are other residual benefits to this system, as well. “All of the SDGs are related,” notes Cuevas, referring to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. “When we are treating water with micro-algae, the micro-algae is also storing carbon, so it’s a carbon-drawdown solution. And water is a super-important resource, which we are going to have to take care of with the crisis of climate change. So the main source of water we are saving is ground water. When we store more ground water, and stop using as much, the opportunities of adapting to climate change multiply.”

FAMILY EXPERIMENTS

Cuevas’ passion for science was stoked growing up the daughter of two chemists, whose idea of family fun was conducting experiments in which Cuevas and her siblings could participate.

“My dad would bring home different polymers,” she recalls, “that we would boil and try to form into new shapes. On vacations, we would do experiments, like evaporating sea salt from salt water, and then playing with the crystals to see what you could do with them, depending on the temperature. On a sunny day and a cloudy day, the formation of the crystals would be different.”

After a summer class at Singularity University, her interests veered toward biotechnology. “we could rediscover everything. Artificial Intelligence, 3D printing — this is the future for environmentalism. If we can learn these things to protect the planet, there is no limit.”

The goal down the line for Cuevas and microTERRA — which won’t be market ready until 2021 or 2022 — is to address similar pain points not just for aquaculture farmers, but for all livestock farmers. She believes the same solutions can be derived for pig and cattle farmers.

“We talk a lot about manure,” she says with a laugh.

But her mission is very serious. “The kind of pollution we are fighting is less visible to the eye, because it’s microscopic. But if you turn the biggest pollutant into resources, then you no longer have any problems. Instead of seeing something as a problem, we see it as an opportunity.

This article originally appeared on Earth’s Call.