Missing pathways to 1.5°C

An unprecedented alliance of social movements, conservation groups, faith-based organizations and scientists have launched a major report that shows how transformations in the land sector represent the ‘missing pathways’ toward the 1.5°C temperature limit.

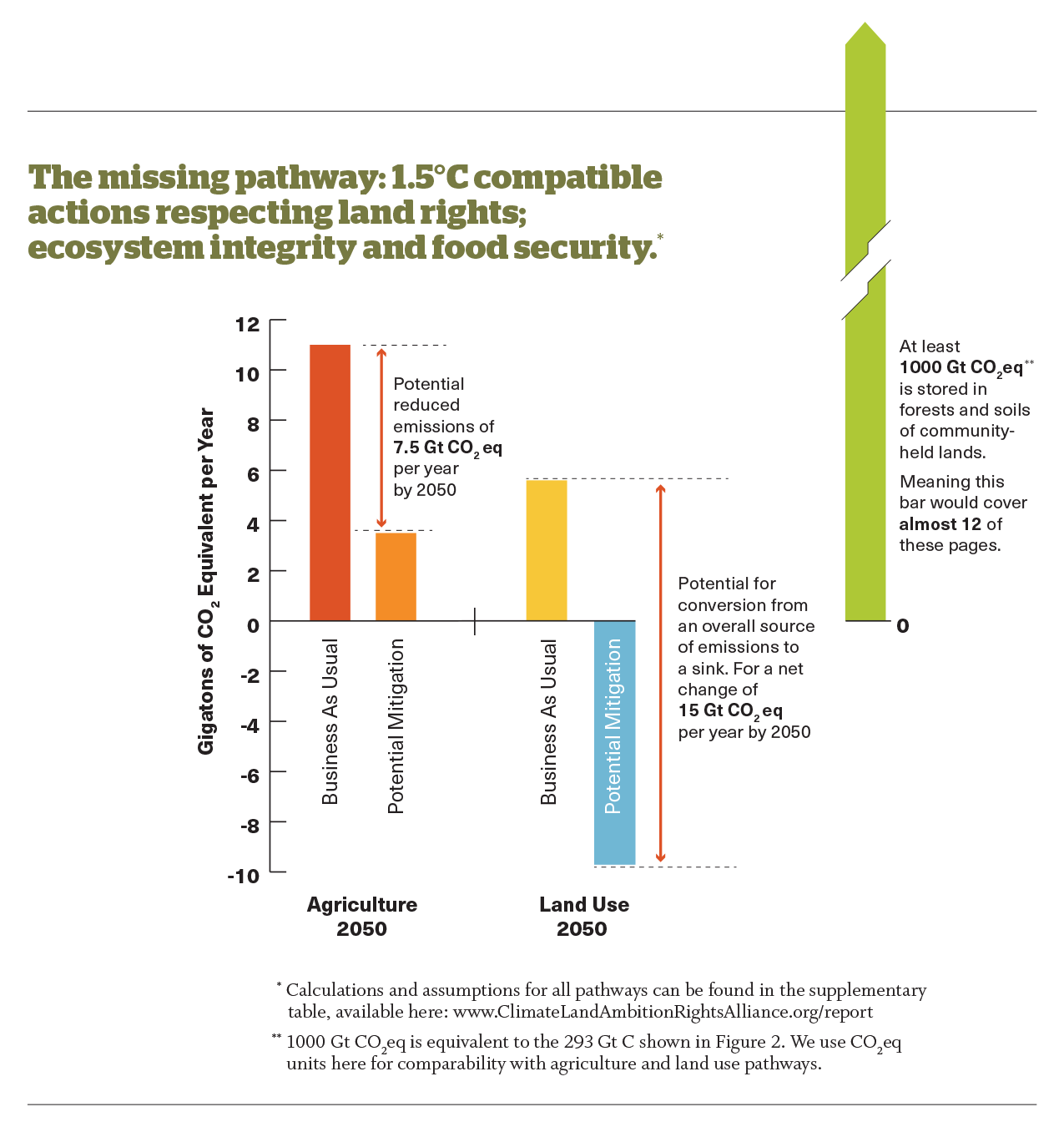

The new report from the Climate, Land, Ambition and Rights Alliance (CLARA) responds to the concern that many IPCC pathways rely on untested mitigation approaches such as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), which require large amounts of land and may even increase emissions. CLARA supports the IPCC’s message that action on climate change is urgent, as is meeting the sustainable development goals. So the report asks - what level of climate ambition can be based on approaches that are already available, and that safeguard food sovereignty, land rights, and ecosystem integrity?

Synthesizing a broad range of scientific literature, the report demonstrates (and quantifies) the potential for targeted policies in the land sector to reduce the sustainability risks associated with climate action. Along with the total phase-out of fossil fuel use, these actions represent the missing pathways to 1.5°C that have so far received little attention from policy-makers.

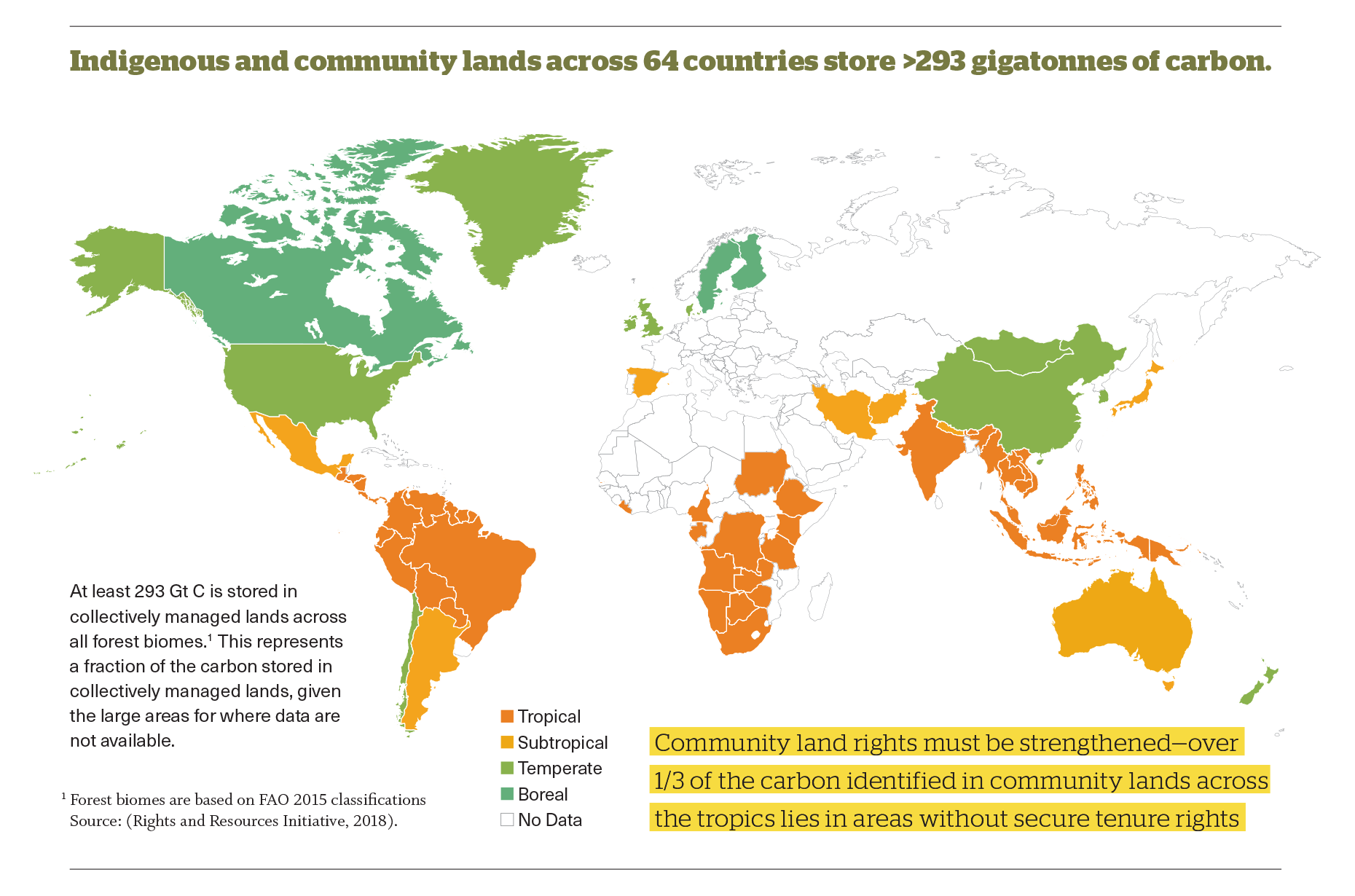

First off, the report finds that securing collective land rights for Indigenous peoples and local communities represents the most effective, efficient and equitable action that governments can take to protect the world’s remaining natural forests. With half of the world’s land associated with a ‘customary land-use’ claim, a large portion of the remaining global forest estate is under Indigenous and community management, yet only 10% of this land has secure legal title. An enormous volume of carbon is protected in the forests and soils of collectively held lands – strengthening customary land rights is the most effective way to ensure this carbon stays in the ground.

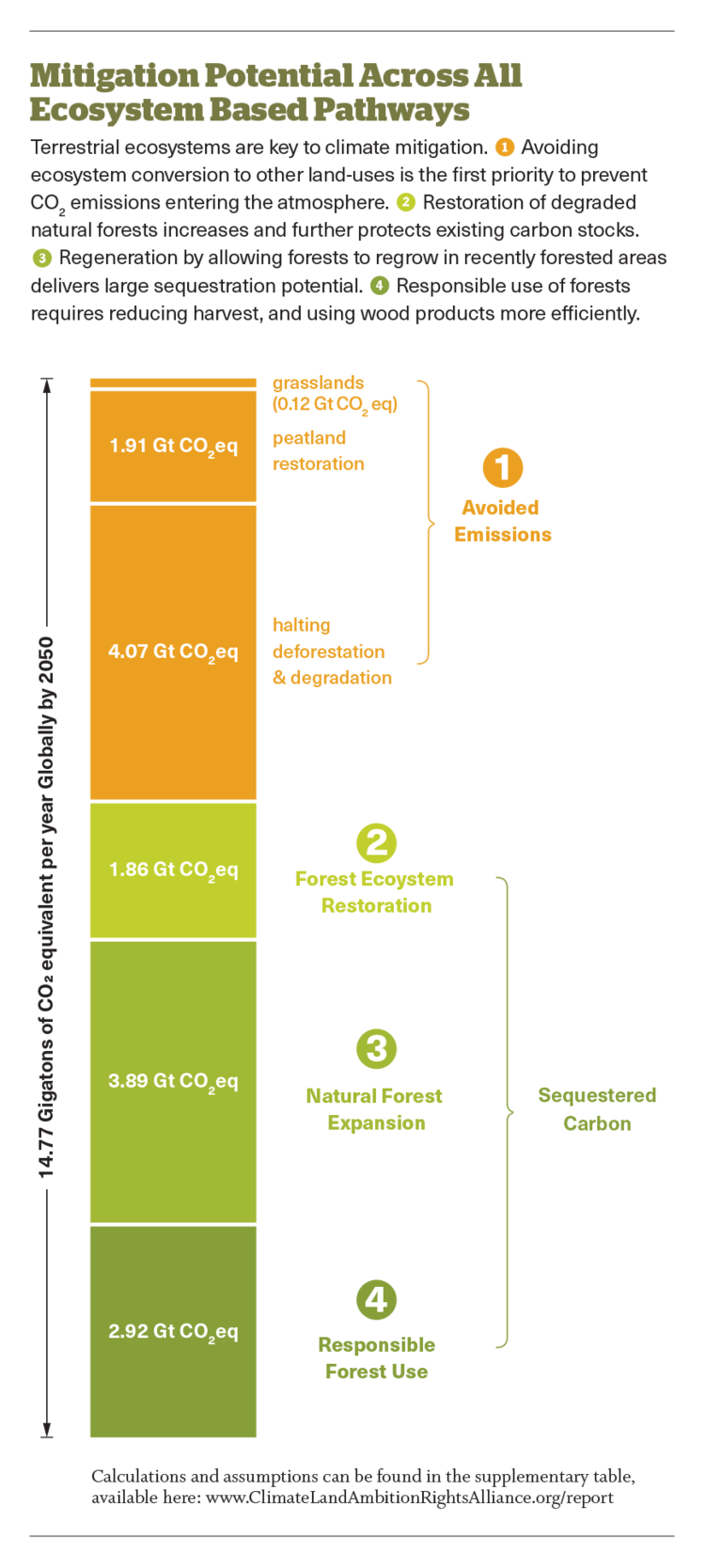

Second, the report quantifies the mitigation potential of preventing further emissions from the conversion of natural ecosystems, and the restoration, regeneration, and improved management of native forests. The report quantifies the mitigation value of protecting half of the planet’s natural forests, which is crucial for planetary stability. This requires the restoration of degraded forests and regeneration to buffer remaining primary forests. The regeneration of native forests sequesters carbon, protects biodiversity and provides ecosystem integrity, all crucial for the long-term resilience of forests. Monoculture plantations, in contrast, create carbon losses and are highly susceptible to fire and disease.

The responsible use of forests is also important to improve ecological values and enhance carbon sequestration in forests managed for timber production. Reducing harvest rates and lengthening rotation times can double the amount of carbon stored in managed forests. In tropical forests, responsible use means no commercial extraction of timber, given that over half of the biomass in these forests resides in valuable hardwood trees that take centuries to regrow. More efficient wood production, reduced wood consumption, zero waste of wood products and more recycling are all needed to reduce the pressures that drive the destruction and over-use of native forests.

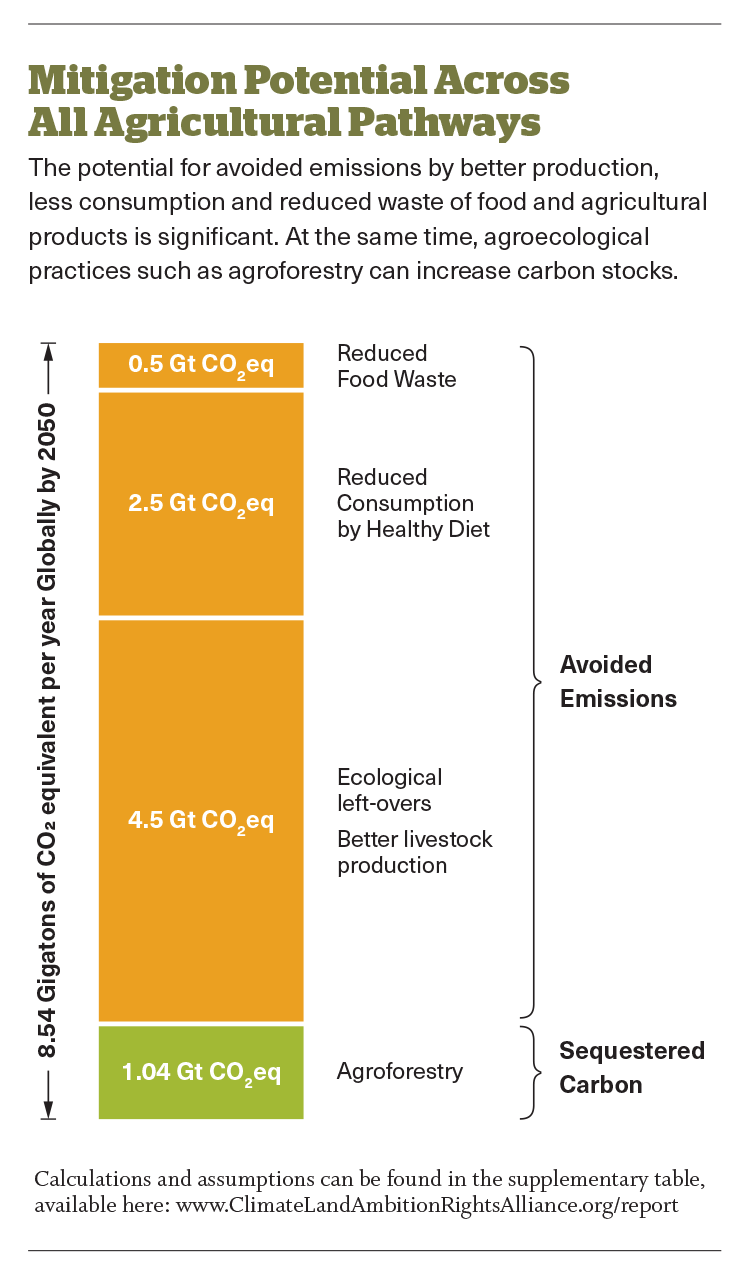

Third, the report outlines how agroecology presents an holistic alternative to industrial farming that provides health, livelihood, resilience, and food system benefits. An important agroecological approach is the introduction of trees into agricultural landscapes – agroforestry, which is widely practiced by smallholder farmers. Agroforestry increases carbon stocks, but also improves soil fertility, provides shade for grazing animals or crops, and multiple other benefits.

Changing the way that animal products are produced and consumed also provides a large mitigation opportunity. An approach to livestock production called ‘ecological left-overs’ relies on natural grasslands and food waste to feed livestock, rather than growing crops to feed to animals. This means more efficient and less intensive livestock production, which relies on reducing the amount of meat and dairy products consumed. Limiting consumption of meat, dairy and overall calorie intake to healthy levels globally (which requires significant dietary changes in rich, developed countries) significantly reduces emissions. Reducing food waste, food miles travelled, and wasteful food production systems can also lower greenhouse gas emissions.

In conclusion, the CLARA report offers solutions to the climate crisis that are ready to implement now, or are already being implemented (such as indigenous land stewardship), and need to be recognized and supported as effective climate strategies. Taken together, all of the above strategies could add up to a mitigation potential of 23 Gt CO2eq per year, as summarized in Figure 4.