Regionally adapted seeds, resiliency, and unity with Earth

- Regenerative Agriculture

- Regenerative Croplands

- Bioregional Sourcing

- Seed Diversity

- Northern America Realm

Our global industrial agricultural system based on extraction, exploitation, and waste has been a major contributor to pollution, deforestation, climate change, unprecedented biodiversity loss, inequality, and the emergence of disease. As the global pandemic intensifies, national and global food supply chains, too large and inflexible to adapt to shifting market demand, are crumbling. The quiet rumbles of food shortages can be heard and felt.

These growing pains are bringing to the forefront the importance of small-scale local food production and regional food systems more in sync with nature.

Resilient food systems are by no means new, as they have been utilized for upwards of 10,000 years since our ancestors began domesticating our major food crops and forming civilizations. In fact, a majority of food consumed globally is still produced on two hectares of land or less often using minimal inputs, locally adapted seeds, and in sync with the function of the Earth.

However, in the United States, the introduction of hybrid corn, while playing a major role in pulling us out of the Dust Bowl and Great Depression, played a large role in decoupling farmers from the process of saving and adapting seeds to local and regional conditions, and was followed by massive consolidation of our farmland, food production, and seeds. While such consolidation is efficient when things are stable, though often at a cost to natural resources and human dignity, diversification across all levels of our food system is imperative to adapt to change.

This is because diversity is the material on which evolution depends; no diversity equals an inability to cope with change. It is time to transform our food systems back into local and regional ones that are resilient to change.

Chickpea (Cicer arietinum) landrace from Siirt, Turkey, being grown in Greater Kansas City by The Buffalo Seed Company to increase crop diversity in the Midwest. Image credit: Courtesy of Dr. Matthew A. Kost

Local and regional seed systems are at the heart of resilient food systems, and it is time to strengthen them as we transform the latter into a form more in sync with the pulse of the earth. Locally grown seeds, produced using minimal inputs, adapt to the environment they will be planted in, which reduces the need for inputs when growing food.

Plant a diverse maize population with the rains and don’t irrigate, some will die, and the seeds will adapt to local conditions while still maintaining diversity to adapt to future change—locally and regionally, adapting seeds function in sync with local ecosystems. A number of seed companies purchase seeds wholesale from regions or countries different than where they will be planted, where the seeds are often pampered to increase yields and buffer evolution, meaning more inputs will need to be used when planting for food production.

To live with the Earth in a sustainable manner, we now must grow food with seeds adapted to the locations where we are, locally and regionally, where our seeds know the land, where they know us and us them—unity is the way forward. Ask how and where the seeds you are purchasing are produced. Ask and request seeds grown locally and regionally, seeds that come from places that match your climate.

The global pandemic and subsequent disruptions to food supply chains have driven increased interest in growing food locally, which has strained the seed supplies of larger seed companies. Importantly, many small-scale local and regional seed companies exist throughout the United States who grow all their own seeds in local and regional climates using ecologically sound methods. These are the seed companies that will be providing the next phase of our transformation to local and regional food systems.

Ironically, they are also the ones who still have seeds for sale following the pandemic seed rush.

Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris; top), Mixed Tepary Beans (Phaseolus acutifolius; middle), Japonica Striped Maize (Zea mays ssp. Mays; bottom), and Basket Devil’s Claw (Proboscidea parviflora; right) seeds from Tucson, Arizona, before planting into Kansas soil. Image credit: Courtesy of Dr. Matthew A. Kost

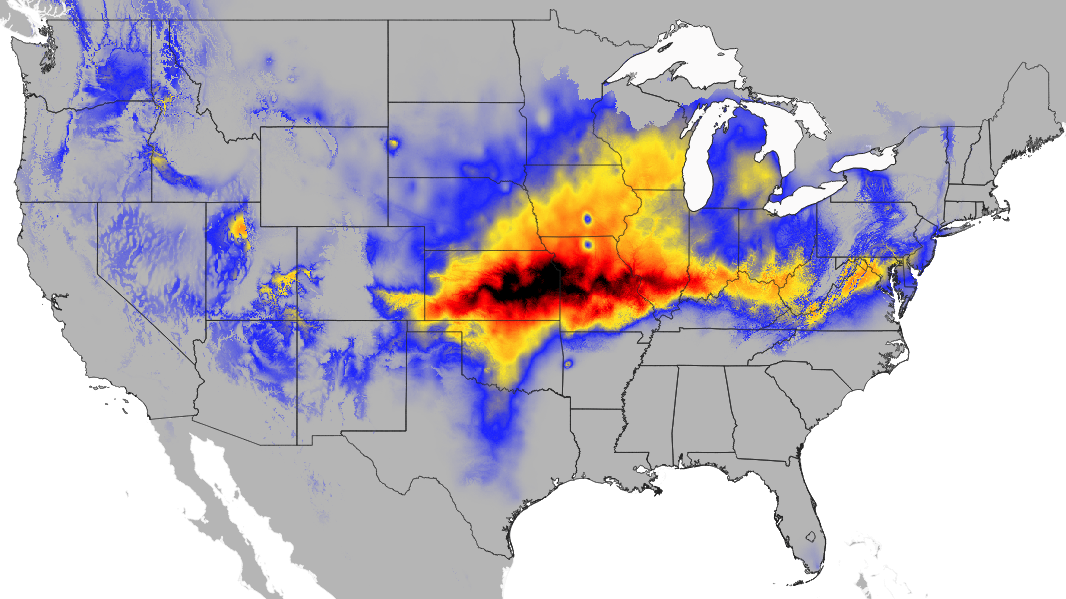

The Buffalo Seed Company for example, located near Kansas City, sells a diversity of seeds that they grew with no field irrigation and minimal organic inputs. The map below shows the areas of the United States that match the climate where they grew their seeds. The order of greatest match is black, then red, orange, yellow, and blue-purple.

While their seeds will likely grow well throughout the United States, growing their seeds in the colored areas are most likely to lead to the best yields with minimal inputs.

Topological map depicting locations in the mainland United States that match the current climate (temperature and precipitation) of The Buffalo Seed Company’s production site near Kansas City. Colored regions are likely to lead to the best crop production of their seeds though other regions also may lead to strong crop production. CCAFS Climate Analogues tool was used to generate the map. Image credit: Courtesy of Dr. Matthew A. Kost

There are many exceptional local and regional companies also growing their own seeds throughout the United States; in fact, too many to list here. Two great community resources, SeedLinked and The Rocky Mountain Seed Alliance, provide directories that include a number of fabulous local and regional seed companies. Identify the companies located in your region, ask them if their seeds were produced in the region, and ask them how the seeds were grown.

It is time for us to transform our food systems to a state more in sync with the earth, one seed at a time.

Learn why regenerative agriculture is key to solving the climate crisis