Appalachian-Blue Ridge forests

The ecoregion’s land area is provided in units of 1,000 hectares. The conservation target is the Global Safety Net (GSN1) area for the given ecoregion. The protection level indicates the percentage of the GSN goal that is currently protected on a scale of 0-10. N/A means data is not available at this time.

Bioregion: Appalachia & Allegheny Interior Forests (NA24)

Realm: Northern America

Ecoregion Size (1000 ha):

16,360

Ecoregion ID:

331

Conservation Target:

57%

Protection Level:

1

States: United States: AL, GA, TN, SC, NC, VA, WV, MD, PA, NY

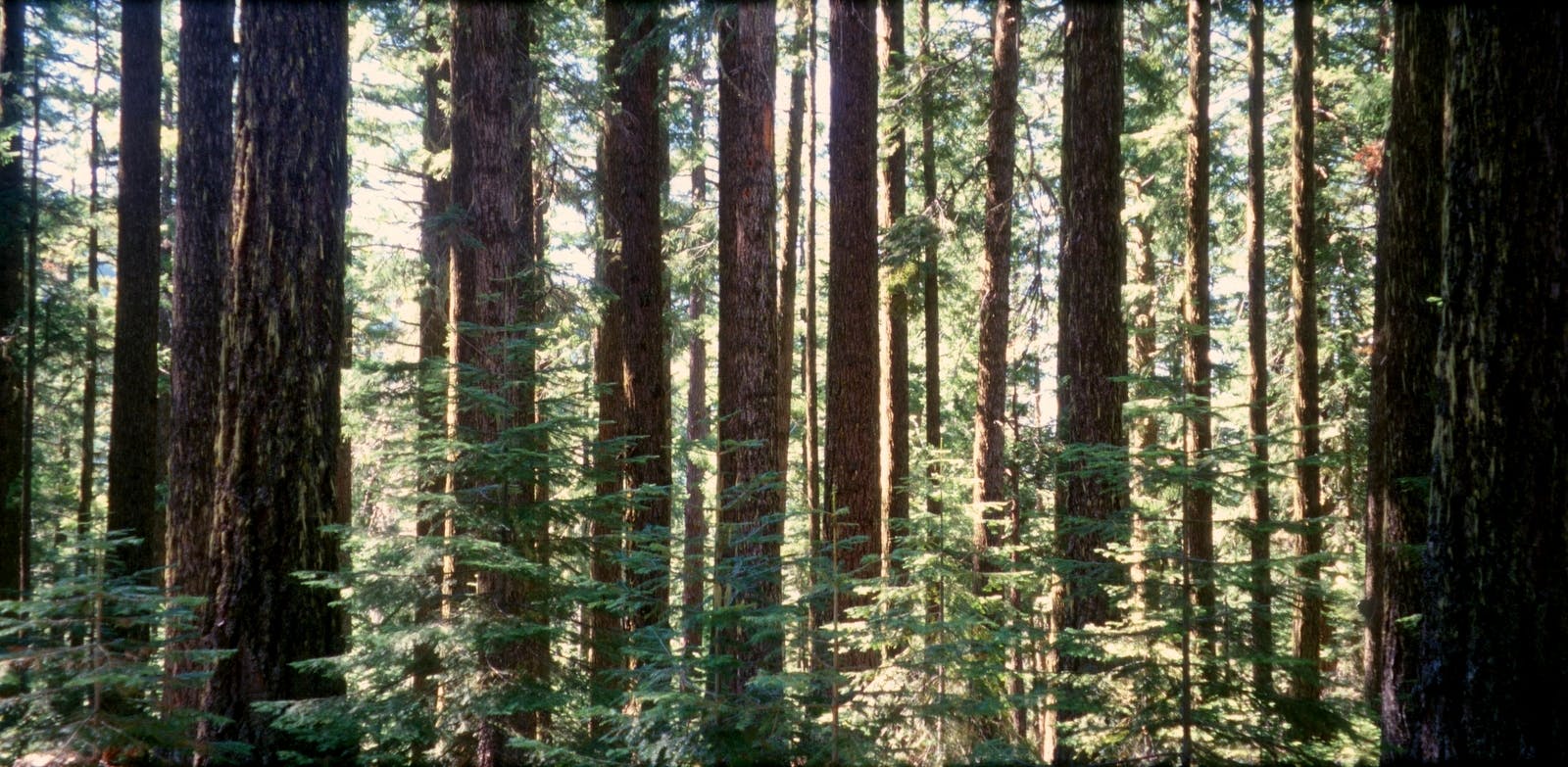

The Appalachian-Blue Ridge Forests ecoregion includes the Blue Ridge and Valley and Ridge physiographic provinces, a long region stretching from central Alabama northeastward to New York state and including portions of 10 states. The Appalachian Mountains are an ancient range, first arising roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period and with subsequent periods of uplift since then. They were once as tall as the Rocky Mountains before being reduced by the natural process of erosion.

This ecoregion has a long evolutionary history and is one of the hotspots of temperate biodiversity in the world. More than fifty plant genera, including magnolias, hickory, sassafras, persimmon, ginseng, and mayapple, have disjunct (separated) distributions between the Appalachians and eastern China, reflecting formerly widespread ranges that were disrupted by climatic changes.

Hellbender salamanders, copperhead snakes, paddlefish, and several other animals show similar disjunct patterns between the Appalachians and eastern Asia.

The flagship species of the Appalachian-Blue Ridge Forests ecoregion is the hellbender salamander. Image credit: Creative Commons

The climate of the Appalachian-Blue Ridge Forests ecoregion ranges from warm to cold temperate. Rainfall is moderate to very high, with some peaks in the southern Appalachians receiving around 2286 mm of rain annually. Climate has been relatively stable over time, which explains the persistence of ancient, relict plants and animals.

Given the breadth of elevations and landforms, the natural vegetation is extremely diverse, ranging from temperate oak-hickory and mesic cove forests at lower elevations to spruce-fir forest reminiscent of boreal Canada and heath and grassy balds at high elevations. American chestnut was a dominant tree at lower elevations, but it is now nearly extinct in the wild due to introduced chestnut blight.

Besides forests, other communities include glades, serpentine barrens, rock outcrops and granitic domes, caves, and a variety of grasslands and bogs. Near the southwestern tip of the ecoregion in central Alabama is the unique Bibb County (Ketona) glades, an outcrop of unusually magnesium-rich dolomite above the Little Cahaba River. This small site contains more than 60 species of rare plants, including 9 local endemic plant species that are new to science since the 1990s.

Diversity of plants and animals in this ecoregion and the adjacent Appalachian mixed mesophytic forests ecoregion is higher than in any temperate forest region in the world except China. Approximately 160 species of trees can be found here.

The region is a global center of evolution and diversity for the lungless plethodontid salamander family. These salamanders collectively have higher biomass than any other animals in the forest. More than 70 species of salamanders in this family occur in this ecoregion, a temperate zone record. Many of these species have been only recently described, and probably more remain to be discovered.

The diversity of fishes, mussels, snails, crayfish, stoneflies, and some other freshwater groups in this ecoregion’s streams and rivers are virtually unsurpassed globally. The Tennessee-Cumberland and Mobile river basins of this and adjacent ecoregions are the premier freshwater biodiversity hotspots in the temperate world.

Fraser fir foliage. Image credit: Creative Commons

The Appalachian-Blue Ridge Forests ecoregion has been altered by logging, agriculture, coal mining, and exotic species, though fortunately as much as 64% of natural habitat still remains outside of protected areas. Fraser fir and eastern hemlock trees are succumbing to introduced wooly adelgid insects. Urban sprawl is now also prevalent. An urban growth model for the southeastern U.S. shows particularly intensive urbanization in this region, as well as the Piedmont and central Florida, by the year 2060.

Priority conservation actions for the next decade are: 1) greatly increase federal, state, and local acquisition of conservation lands, and improve management of existing conservation lands; 2) reduce or eradicate populations of problematic exotic species, such as adelgids; and 3) reintroduce populations of extirpated species such as blight-resistant American chestnut and eastern cougar.

Citations

1. Stein, B.A., L.S. Kutner, and J.S. Adams, editors. 2000. Precious Heritage: The Status of Biodiversity in the United States. Oxford University Press, New York.

2. Edwards, L., J. Ambrose, and L.K. Kirkman. 2013. The Natural Communities of Georgia. University of Georgia Press, Athens.

3. Ricketts, T.H. et al. 1999. Terrestrial Ecoregions of North America: A Conservation Assessment. Island Press, Washington, D.C.