Patía valley dry forests

The ecoregion’s land area is provided in units of 1,000 hectares. The conservation target is the Global Safety Net (GSN1) area for the given ecoregion. The protection level indicates the percentage of the GSN goal that is currently protected on a scale of 0-10. N/A means data is not available at this time.

Bioregion: Andean Mountain Forests & Valleys (NT11)

Realm: Southern America

Ecoregion Size (1000 ha):

228

Ecoregion ID:

542

Conservation Target:

11%

Protection Level:

0

States: Panama

The steely-vented hummingbird is metallic green and is an active resident in the dry Patía valley amidst the cloud forests of the high Andes. These little birds prefer forest gaps and have been able to cohabitate with the humans that now dominate the valley by adapting also to secondary growth forest, coffee plantations, and gardens. Their nests are unique not only in their small size, but in the way that cobwebs and plant pieces are woven together and decorated with lichen as camouflage. The hummingbirds’ almost invisible nests help to hide their eggs and hatchlings, which must be fed incessantly until they fledge to fly amongst the flowers of the Patía Valley Dry Forest.

.jpg)

The flagship species of the Patia Valley Dry Forests ecoregion is the steely-vented hummingbird. Image credit: Arley Vargas, Creative Commons

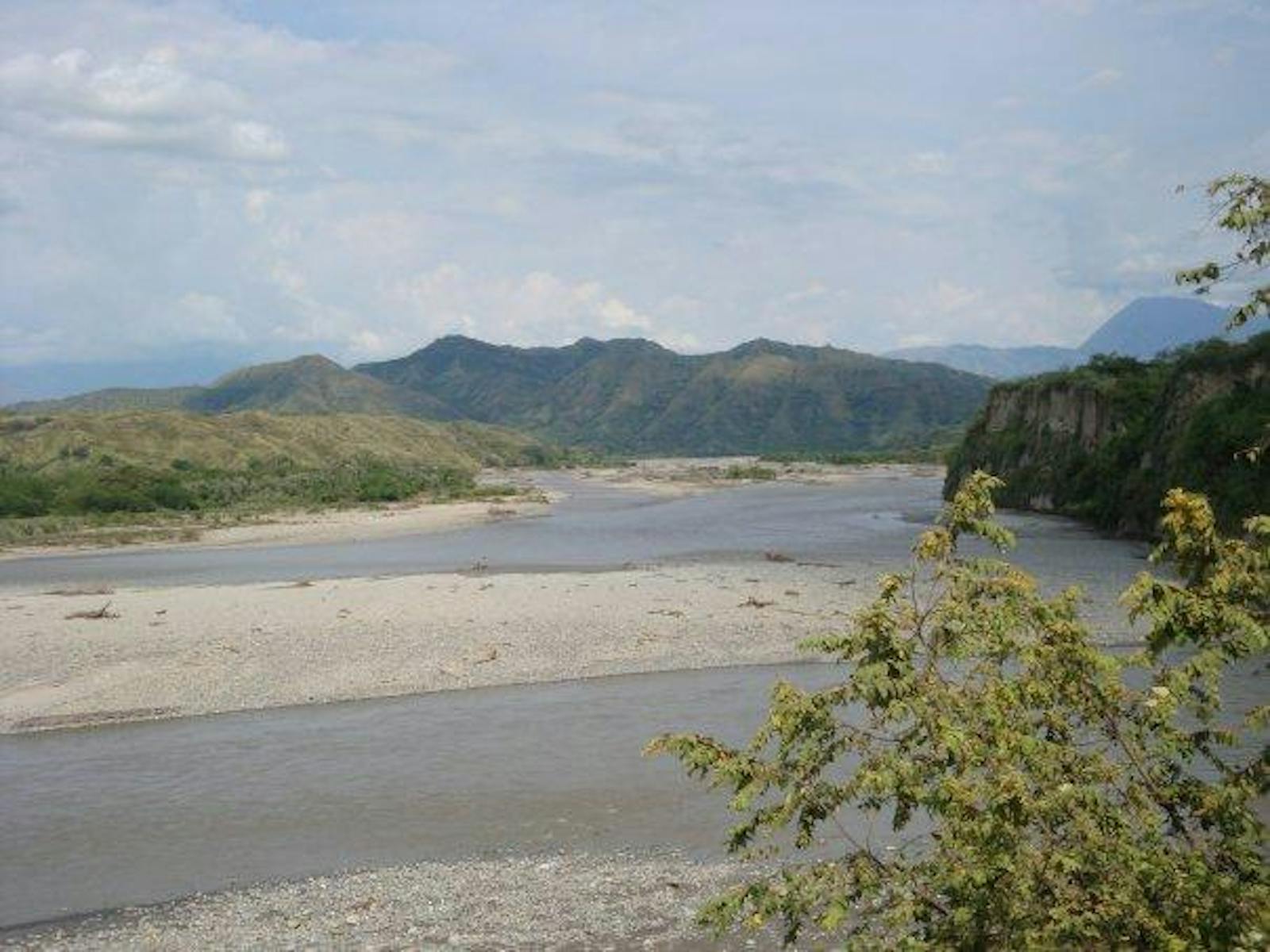

The Patía Valley is a dry pocket “valley” surrounded by the cloud forests of the Central and Western cordilleras of Colombia. It is dissected by the Patía river, which flows from the Colombia’s central massif westwards and breaks the Western cordillera to drain into the Pacific Ocean, after receiving water from the Chocó jungles of the Pacific region of Colombia. The middle course of the Patía river forms the Patía dry valley. This dry pocket has a unique set of plants and animals that has adapted to the arid environment.

This valley has a mean altitude between 600 and 900 m above sea level. Its climate is highly seasonal, with rainy seasons between April and June and again between October and November. The mean rainfall is less than 900 mm per year. The soils are of sedimentary origin, with pockets of volcanic ashes from nearby Puracé and Sotará volcanoes. The Patía is the main river but it receives the waters of the Quilcacé, Guachicono, Mayo, Juanambú, Pasto and Guaitara rivers.

Today, the most common vegetation is represented by Calabash tree, bay cedar, purging cassia, palo santo, yellow mombin, algodoncillo, kapok, and mata ratón. The cactus Pilosocereus colombianus is also present, along with prickly pears. The spectacular orchid, Schomburgkia splendida, grows on top of boulders and rock outcrops.

Lesser Antillean saltator. Image credit: Erika Mitchell, Creative Commons

Little is known about the flora and fauna of this ecoregion. Although no endemism has been found at the species level, there are several sub-species of birds, butterflies and plants that are endemic to this valley. A subspecies of the steely-vented hummingbird and of the streaked saltator are two examples. The mammal fauna was quite rich until recently; collared peccary, red brocket deer, Central American agouti, ocelot, and puma still inhabit the most remote places along the valley. The steep walls of the Juanambú and Guaitara rivers were the nesting place of a relict population of the Andean condor, which is now extinct in the region.

Central American aougti. Image credit: Geoff Gallice, Creative Commons

Today, most of the valley has suffered from human activity. Threats to this valley include all the ramifications of human encroachment: overhunting, urban sprawl, conversion to agriculture, fuelwood overcollection, and grazing of livestock. Several major roads cut directly through this valley, which further exacerbate habitat fragmentation in the region. Several pockets of the original vegetation remain, and can be preserved. Conservation initiatives in some private lands could potentially sustain a considerable proportion of the original species. But, in general, conservation actions are urgently needed in this valley to protect the remaining original ecosystems.

The priority conservation actions for the next decade will be to: 1) establish protected areas in order to conserve what original habitat that still remain; 2) promote conservation of both the habitat and species in private lands; and 3) educate local communities in order to prevent overhunting of species and overharvesting of fuelwood.

Andean Condor in flight. Image credit: Pedro Szekely, Creative Commons

Citations

1. Complejo Ecoregional de los Andes del Norte (CEAN). Experts and ecoregional priority setting workshop. Bogota, Colombia, 24-26, July, 2000.

2. Hernández Camacho, Jorge, et al. 1992. Unidades biogeográficas de Colombia. In Gonzalo Halffte, editor, La diversidad biológica de Iberoamérica Mexico: Acta Zoológica Mexicana, CYTED-D.

3. Hernández Camacho, Jorge. 1995. Desiertos, zonas áridas y semi-áridas de Colombia. Diego Samper Ediciones. Banco de Occidente, Colombia.