Meet the Buru babirusa: The mysterious deer-pig of Indonesia's rainforests

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Iconic Species

- Wildlife

- Mammals

- Australasian Islands & Eastern Indonesia

- Australasia Realm

One Earth’s “Species of the Week” series highlights an iconic species that represents the unique biogeography of each of the 185 bioregions of the Earth.

In the dense tropical forests of Indonesia, an extraordinary animal roams the riverbanks and upland jungles—a wild pig that resembles a mythical beast. With upward-curving tusks that pierce through its own snout and a shaggy golden coat, the Buru babirusa (Babyrousa babyrussa) is one of nature’s most unusual and elusive mammals.

Revered in ancient cave art and protected by law today, this “deer-pig” tells a story of deep time, cultural connection, and urgent conservation.

The Buru babirusa is the iconic species of the Sulawesi & Maluku Islands bioregion (AU14), located in the Australasian Islands & Eastern Indonesia subrealm of Australasia.

Native range spanning three Indonesian islands

The Buru babirusa is found only on the remote Indonesian islands of Buru, Mangole, and Taliabu. These islands lie within the Maluku region, far from the better-known jungles of Sumatra or Borneo.

The species prefers tropical lowland and hill forests near riverbanks, swampy areas, and forest ponds rich in aquatic plants. Although babirusas were once more widespread in coastal lowlands, they are now largely confined to higher-elevation interior forests, where logging roads and poaching pressure have yet to reach full force.

Three species of a once singular genus

Until 2001, all babirusas were classified under a single species. However, scientists have since recognized three extant species:

- Buru babirusa (Babyrousa babyrussa) – golden-haired and found only on Buru, Mangole, and Taliabu.

- North Sulawesi babirusa (B. celebensis) – mostly hairless, found on Sulawesi’s northern peninsula.

- Togian babirusa (B. togeanensis) – slightly hairy, native to the Togian Islands in the Gulf of Tomini.

Each species exhibits subtle differences in skull shape, hair coverage, and tusk structure, but all share the babirusa’s distinctive curling tusks and striking appearance.

Physical traits that set them apart

The Buru babirusa, also known as the golden or hairy babirusa, is easily recognized by its long, thick, golden-brown coat, a trait not shared by its mostly bald relatives. Males display the babirusa’s iconic upward-curving tusks, which are upper canines that grow through the snout and arch back toward the forehead.

Females have much smaller or absent tusks, and all babirusas share the rare trait of having only one pair of teats.

The male babirusa’s upper canines grow through the top of its snout and curve backward toward the forehead, an anatomical feature found in no other wild pig. Image credit: © Jpldesigns | Dreamstime

A varied diet and an unusual way of eating

All babirusas are omnivores, feeding on leaves, roots, fruit, and animal matter. Unlike other pigs, they do not root in the ground due to the absence of a rostral bone in their snouts, though they may dig in mud or soft earth.

Their powerful jaws can crush hard nuts with ease, making them well-adapted to forest foraging. Although their stomach includes an enlarged pouch once thought to indicate ruminant behavior, they do not chew cud.

A forest forager with an important ecological role

As forest foragers, Buru babirusas play a key role in nutrient cycling and seed dispersal through their droppings. Their digging helps aerate soil and promotes plant growth.

By feeding on a variety of plants, they help maintain the ecological balance in the forest understory. As prey to large predators, they are an integral part of the ecosystem.

Behavior and social structure in the wild

Babirusas are diurnal and exhibit different social behaviors based on sex. Adult males are typically solitary, sometimes forming small groups of two or three. Females and their young may gather in larger groups, sometimes up to 84 individuals, although usually with no more than three adult females.

Males use their tusks in dominance contests, with the upper tusks serving a defensive role and the lower tusks used offensively. If not worn down through activity, tusks can grow long enough to pierce the animal’s own skull.

A mother Buru babirusa and her piglet. Image credit: Animalia.bio

Reproduction and life cycle

Females reach sexual maturity between 5 and 10 months of age and give birth to one or two piglets after a gestation period of about 150 to 157 days. Newborns weigh between 15 and 35 ounces (380 to 1,050 grams) and nurse for six to eight months.

The Buru babirusa can live up to 24 years, but its slow reproductive rate makes recovery difficult when populations decline.

Ancient art reveal a deep cultural connection

The babirusa has long captured the imagination of the people sharing its island home. A vivid example of this connection is found in the limestone caves of southern Sulawesi.

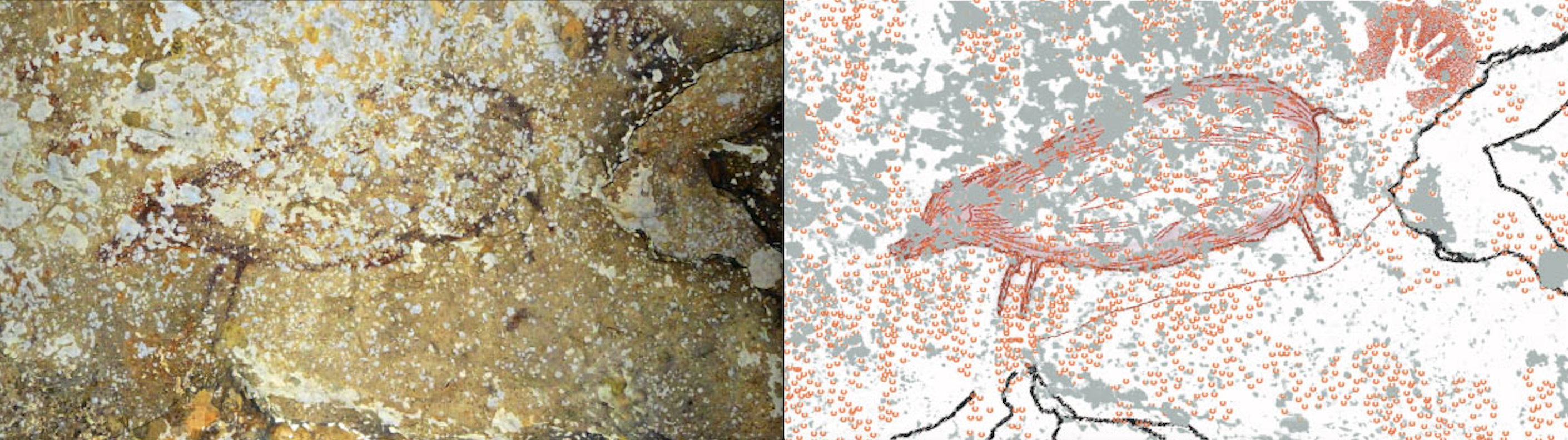

In Leang Timpuseng cave, a painting of a female babirusa has been dated to at least 35,400 years ago, making it one of the oldest known figurative depictions of an animal. Found alongside a 39,900-year-old hand stencil, these artworks show that early modern humans in Indonesia were engaging in symbolic artistic expression deep in prehistory.

Created with blown pigment for handprints and detailed brushwork for animals, the cave art features native Sulawesi species like the anoa and Celebes warty pig. Yet, the babirusa stands out, with its surreal tusks and unique form, suggesting it held special significance to ancient artists.

A 39,900-year-old hand stencil and a 35,400-year-old painting of a female babirusa inside Leang Timpuseng cave, Sulawesi, Indonesia (left). An illustration showing what the image would have looked like. (right). Image credit: M. Aubert et al

The threats babirusas face today

The Buru babirusa is listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN. Despite legal protection in Indonesia, it continues to face threats from poaching and habitat loss. Its range spans just 20,000 square kilometers across the three islands.

Logging has fragmented its forest habitat, removing vegetation that once served as cover from hunters. As their range shrinks and access becomes easier, these animals face greater risk, especially since they reproduce slowly.

Habitat loss and illegal hunting continue to threaten the Buru babirusas despite legal protections in Indonesia. Image credit: © Slowmotiongli | Dreamstime

Current conservation status and efforts

The Buru babirusa has been legally protected in Indonesia since 1931. Two reserves on Buru—Gunung Kapalat Mada and Waeapo—have been established in part to preserve its remaining habitat.

Conservation initiatives focus on limiting logging, enforcing hunting bans, and involving local communities in protection efforts. Education about the babirusa's ecological and cultural importance is key to ensuring that this golden-haired pig does not disappear from Indonesia’s forests.

As one of Southeast Asia's most visually distinctive and ecologically significant animals, the Buru babirusa stands as a powerful symbol of Indonesia’s rich yet fragile biodiversity.

Support Nature Conservation

_CC-Bernard%20Dupont-2013_resized.jpg?auto=compress%2Cformat&h=600&w=600)