Bengal tigers: Unsung heroes of the Sundarbans mangroves

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Iconic Species

- Wildlife

- Mammals

- Indian Subcontinent

- Indomalaya Realm

One Earth’s “Species of the Week” series highlights an iconic species that represents the unique biogeography of each of the 185 bioregions of the Earth.

Bengal tigers, with their distinct orange and black-striped coats, captivate the imagination from an early age, helping us learn about colors, animals, and the uniqueness of nature. As “charismatic megafauna”—a term used to describe large animals with symbolic value—Bengal tigers share the stage with species such as African lions, humpback whales, giant pandas, bald eagles, and emperor penguins.

Yet, their pivotal role as the keepers of the Sundarbans mangroves, a jungle swampland spanning the coasts of India and Bangladesh, is often underappreciated. This globally significant biome is one of Earth's primary carbon sinks, a natural system that absorbs and stores carbon from the atmosphere.

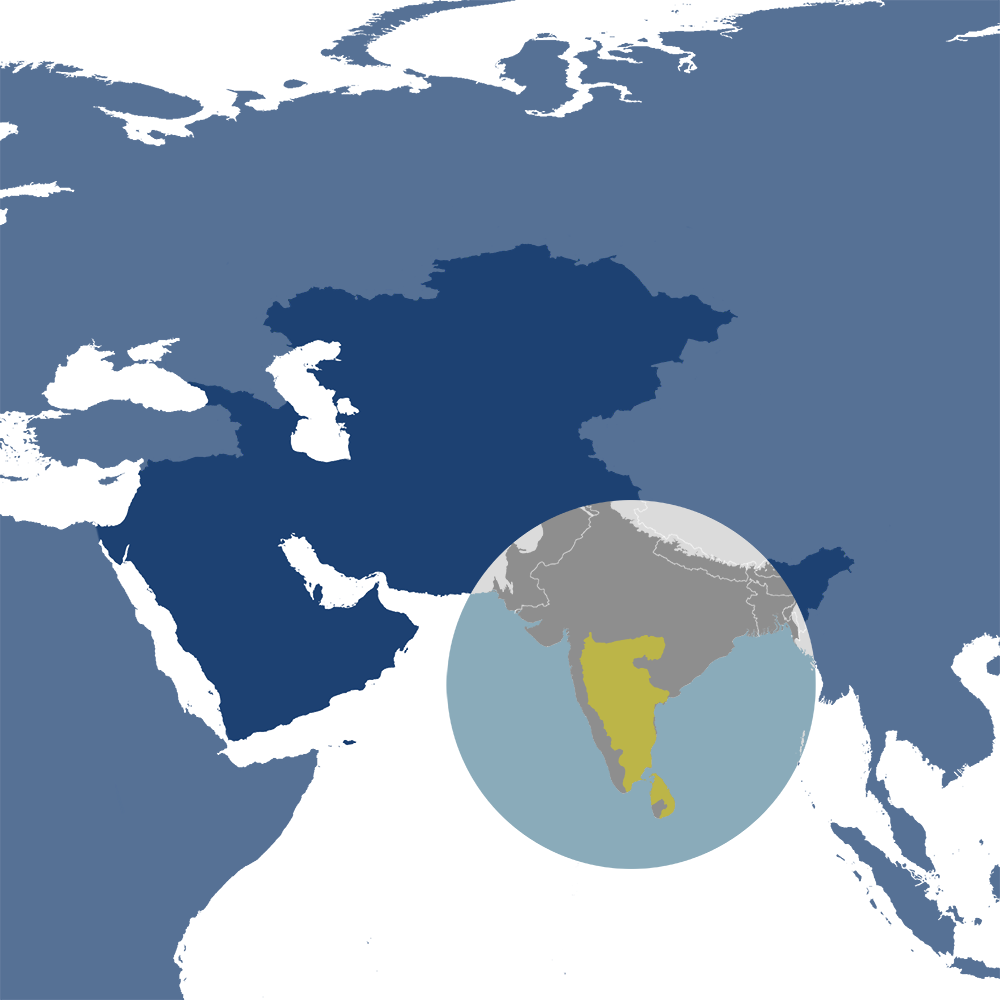

Bengal tigers are the iconic species of the Greater Deccan-Sri Lankan Forests & Drylands bioregion (IM8), located within the Indian Subcontinent subrealm in Indomalaya.

Keeping harmony in the jungle

Sundarbans, translating to 'beautiful forest' in Bengali, offers a lush green cover, with Heritiera fomes trees constituting 70% of the vegetation. It's a hotspot for biodiversity, teeming with 150 species of fish, 270 birds, 42 mammals, 35 reptiles, and eight amphibian species, with new insects and fungi being discovered frequently.

Within this rich tapestry of life, the Bengal tiger, capable of weighing up to 325 kg (717 lb), running 64 kph (40 mph), and consuming 40 kilograms (88 lb) of food at a time, serves as the apex predator. As carnivores, these tigers control mammal populations, which in turn influence the plant species dynamics, enabling mangrove trees to flourish in this biodiverse delta.

Without the presence of these “Royal Bengal Tigers,” as they're often referred to in the region, it's unlikely that this tropical coastal swamp would spread across its impressive 140,000 hectares.

_3_Wikimedia%20Commons.jpg)

Heritiera fomes mangrove trees make up 70% of the vegetation in the Sundarbans. Image Credit: Wiki Commons.

The importance of the Sundarbans

Mangroves play a crucial role in our planet's health by effectively capturing and storing carbon, a process known as carbon sequestration. To put it into perspective, mangroves currently hold carbon equivalent to over 21 billion tons of CO2. A study conducted by Raghab Ray and Tapan Kumar Jana in 2017 found that the Sundarbans absorbed 98% of the carbon produced by a coal-based power plant in Kolaghat, India.

In addition to sequestering greenhouse gases and storing them for centuries, mangroves contribute to oxygen production, purifying the air we breathe. This makes them an indispensable ally in the fight against climate change.

An adult male Bengal tiger in the Sundarban Tiger Reserve, West Bengal, India. Image Credit: Soumyajit Nandy, Wiki Commons.

Protecting tigers to protect the Earth

Bengal tigers, having inhabited the Indian subcontinent since the Late Pleistocene around 12,000 to 16,500 years ago, are instrumental in preserving this vital ecosystem. However, due to poaching and severe habitat loss, the Sundarbans have witnessed a 95% reduction in their historic tiger population.

Encouragingly, conservation initiatives throughout India, Nepal, and Bangladesh have seen the number of wild tigers rise to 3,890 individuals from just 2,000 recorded in the 2000s.

By fostering a conducive environment for the mangrove trees to thrive, these magnificent creatures help keep the air clean, protect coastal communities from flooding, secure the livelihoods of locals relying on the land, and play a pivotal role in climate change mitigation.

Intrigued to learn more about the intricate bioregions of Indomalaya? Explore One Earth's interactive Navigator to delve deeper into bioregions worldwide.

Launch Bioregion Navigator

%20is%20a%20subspecies%20of%20tiger%20found%20on%20the%20Indonesian%20island%20of%20Sumatra%20dreamstime_xxl_14836831%20(1).jpeg?auto=compress%2Cformat&h=600&w=600)