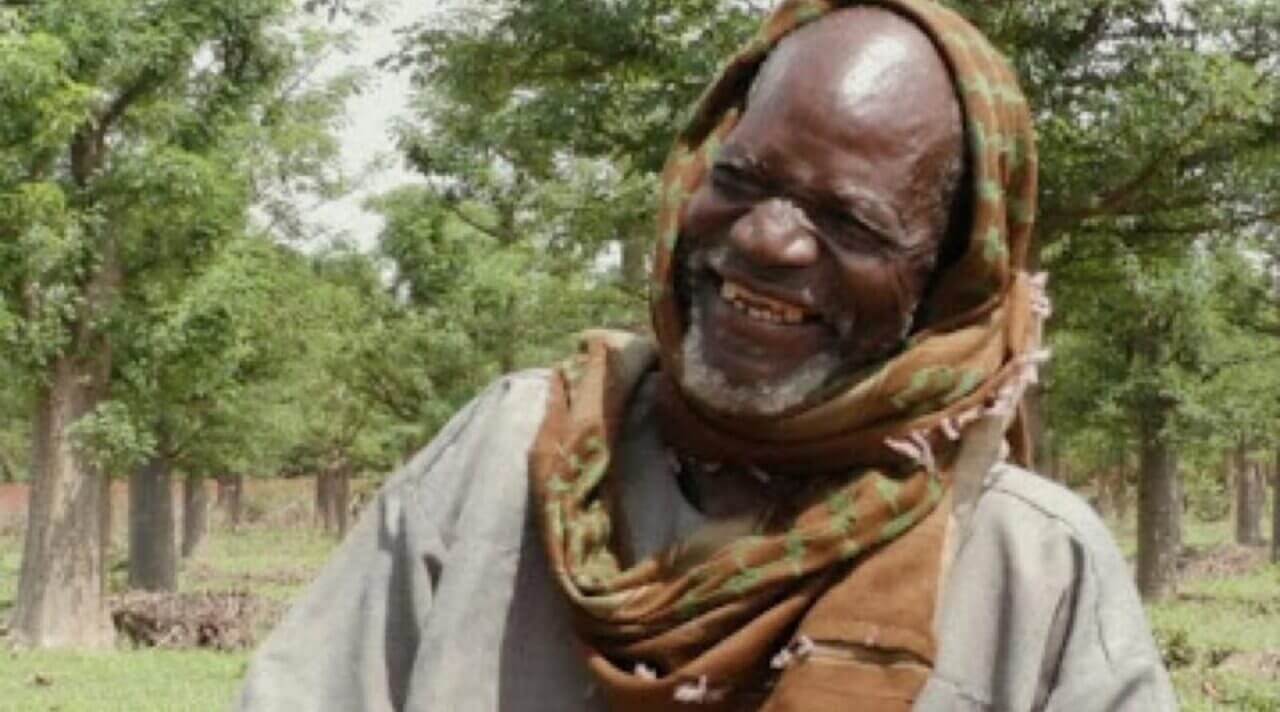

Climate Hero: El Hadji Salifou Ouédraogo

- Nature Conservation

- Ecosystem Restoration

- Forests

- Climate Heroes

- Plants

- Sub-Saharan Afrotropics

- Afrotropics Realm

The African baobab tree (Adansonia digitata) symbolizes thriving life in the arid landscape of the savannah, providing shelter, food, and water for humans and various species. One man has planted thousands of baobab seedlings over the past 47 years, creating a vast forest that helps his family, community, and the Earth flourish. Meet El Hadji Salifou Ouédraogo.

.jpg)

Called to the baobab

Born and raised in Titao, Burkina Faso, Ouédraogo longed to be a Quran Master. However, he felt called to another spiritual route, this time with nature. At first, Ouédraogo started planting mango trees but realized everyone around him was doing the same.

If everyone is running in the same direction, you have to look out for an escape route for when things go wrong.

The urge to be different led him to plant the mighty baobab. People called him crazy, but that encouraged Ouédraogo even more.

In local folklore, whoever plants a baobab dies as the tree is cursed. Legend says the baobabs were too proud, so the gods became angry and uprooted them and threw them back into the ground upside-down.

Ouédraogo told them, “My father did not plant a baobab, but he died. I have never seen my father’s nor my grandfather’s baobab, but they are all dead. If the baobab tree stays alive and I die, it is not a problem.”

The ‘Tree of Life’

Despite the trees' mythology, baobabs are essential to life in the savannah. A succulent, the tree absorbs and stores water from the rainy season in its massive trunk, which helps keep soil conditions humid, slows erosion, and serves as a water source for many animals.

The baobab’s fruit contains tartaric acid and Vitamin C, providing vital nutrients for various species, including birds, lizards, monkeys, and even elephants. For humans, the baobab’s fruit pulp can be eaten, soaked in water to make a refreshing drink, preserved into a jam, or roasted and ground to make a coffee-like substance.

The bark from the tree is pounded to make everything from rope, mats, and baskets to paper and cloth. Leaves are also used, they can be boiled and eaten, or glue can be made from their flower’s pollen.

With over 300 life-sustaining uses, it is the root of many Indigenous remedies, traditions, and folklore. Hence its literal nickname, ‘The Tree of Life.’

A faith and family business

Today, Ouédraogo’s forest has over 3,000 trees and covers 14 hectares. Not only do his baobabs provide food to his fellow villagers, but they also preserve a traditional lifestyle while protecting the climate from deforestation.

Planting baobab trees is now a part of Ouédraogo’s faith. “It’s the most important thing aside from going to heaven.”

In the documentary The Man Who Plants Baobabs, filmmaker Michel K. Zongo followed Ouédraogo around his forest. The charismatic leader showcases his precious baobabs, how he plants them, and who they feed.

In one scene, community members come through the forest, taking smaller trees back to their homes and picking fruit. It is even a family affair with Ouédraogo’s son, Sofiane, assisting in planting, and his daughter, Kalidjata, collecting leaves.

Ouédraogo’s youthful enthusiasm and passion for native planting practices continue to inspire his neighbors and an international audience of climate and environmental activists with the idea that one person can change the world.

Yet, the older man’s face just curls into a wide grin when he is told of his apparent wisdom. “The advantage of age is what you have seen and what you’ve heard and what you've done.” It is also what Ouédraogo continues to do, and that is plant more baobabs.

Explore forest restoration projects.jpg?auto=compress%2Cformat&w=1440)