Cloth, Climate, Carbon, and Capital: Fibers in the Agricultural System

- Regenerative Agriculture

- Circular Fibersheds

- Sustainable Fiber & Pulp

- Green Textiles

- Philanthro-activism

- Nature/Climate Finance

By now, you have probably heard Wendell Berry’s profound reminder that “Eating is an agricultural act.” But we often overlook the fact that choosing the fiber and textile products that surround us every day is an agricultural act as well.

Like food crops, fiber crops are part of an interconnected agricultural system with linked impacts on health, social justice, and the environment. These soil-based fibers feed into a global fiber, textile, and leather industry that is valued at over $1 trillion, projected to grow to $1.6 trillion by 2022. For purposes of comparison, this is roughly twice as large as the global smartphone market. Behind the numbers lies a fundamentally unsustainable and unjust business model—a system that is designed to sell more products to more people each year, while chasing the globe for the cheapest possible materials and labor.

Hulsman ranch. Image credit: Paige Green

Fibers as a part of agriculture

Let’s start with a look at the key crops we rely on for the fibers and textiles that surround us. This category of crops includes both plant-based fibers like cotton, hemp, and flax and animal-based products like wool, alpaca, and leather.

Globally, annual fiber crops are part of dynamic crop rotations. In many cases they are intercropped with annual food crops, including but not limited to wheat, tomatoes, onion, garlic, milo, teff, herbs, and corn. Rangeland fibers such as alpaca, wool, and mohair, as well as hides and leather, are most often byproducts of pasture-based food systems that are centered on grazing animals. These food-fiber systems can also have related benefits through reduction of fire fuel load and improvement of soil health through regenerative cropping and grazing practices. Natural dye crops like indigo, a known nematode suppressant, can also be integrated into food crop rotations. Because of these shifting cropping and grazing patterns, land area dedicated to natural fiber crops varies from year to year.

Fibers can also be derived from forestry systems around the world. Wood-derived fibers such as rayon, Tencel, and Modal, also known as Man-Made Cellulosic Fibers (MMCFs), are made from tree pulp that is treated with high levels of chemical processing. While some of those processes are closed loop, and textile companies have attempted to filter virgin or old growth forest products, using annual crops like hemp or nettles to produce cellulosic fibers generally requires less chemical digestion than tree pulp and allows more options for crop rotation.

.jpg)

Chico flax. Image credit: Paige Green

Fibers, Climate, and the Carbon Cycle

Soil-based natural fiber crops offer the potential to develop more regenerative agricultural systems. They can be part of contributing to a positive carbon cycle. Natural fiber crops are also fully compostable, allowing the development of systems that Fibershed calls “Soil to Soil” and “Climate Beneficial.”

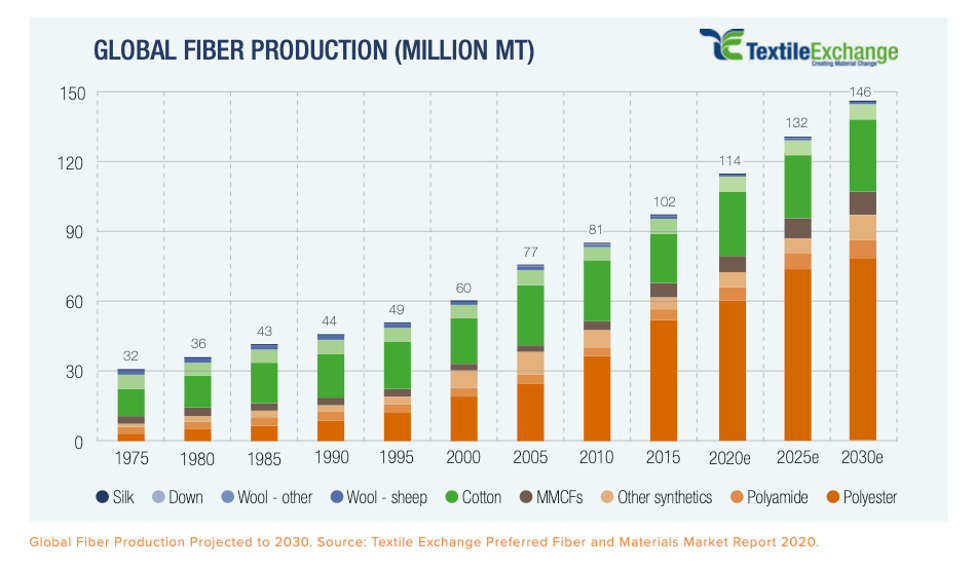

However, this option is being rapidly eclipsed by the skyrocketing use of fossil-fuel derived plastic fibers—such as polyester, nylon, and acrylic—in clothing and home textiles, as shown in the data below from Textile Exchange. Currently, 60-70% of global fiber production is derived from fossil carbon-based plastic fibers. In other words, about two-thirds of all the fabrics we wear or use are made from oil.

Image credit: Textile Exchange

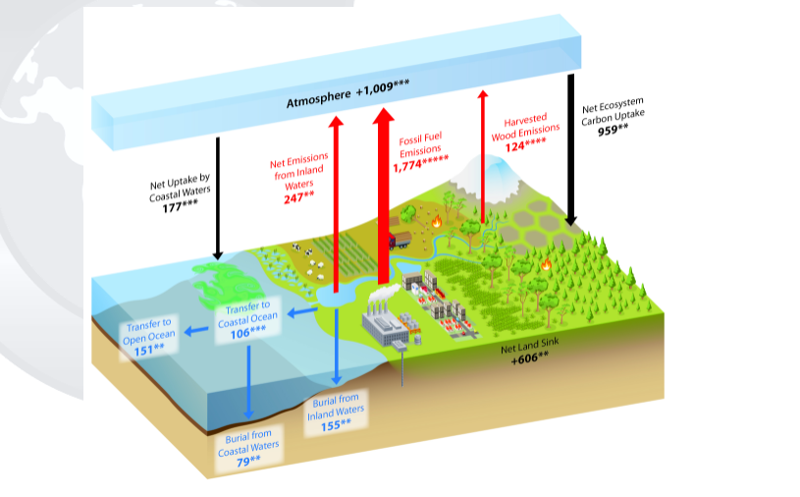

As this diagram shows, these fossil fuel fibers can never be part of net positive change in the global carbon cycle, no matter how often they are recycled. Image credit: Carbon Cycle Science

Furthermore, synthetic fibers remain artificially less expensive than natural fibers due to externalization of the costs of plastic production, and this fact tends to depress demand for natural fibers. As the price of oil is affected by changes in the transportation and energy sectors, fossil fuel conglomerates are increasingly seeking to profit from turning oil and gas into plastics—including plastic textile fibers. Any climate strategy should thus include an awareness of plastic textiles and the textile industry as a whole.

The negative impacts of plastic fibers do not end with their greenhouse gas emissions. Scientific analysis of our marine and soil ecosystems is uncovering the insidious impacts of synthetic plastic fibers that have fragmented from our clothing and into soil, water, and human bodies. Fiber is a dominant component of microplastic contamination found in marine and freshwater systems both globally and in California. In a recent three-year study of microplastics in San Francisco Bay by the San Francisco Estuary Institute, fibers were the most abundant microparticle type found in samples of surface water, wastewater and sediment. 74% of the microparticles in surface water samples were identified as fibers, with more than half of these fibers (53%) identified as plastics. An additional 19% were categorized as “unidentified anthropogenic fibers” and may have included additional plastic.

For all these reasons, we advocate for an intentional focus by funders and investors on soil-based natural fiber crops as a critical component of regenerative agricultural systems. Integrated crop-livestock systems, place-based agroecology, and “carbon farming” are key strategies for increasing the productivity of food and fiber farming systems and supplying our needs with textiles that have natural decomposition pathways. Natural fiber production is capable of meeting human needs as part of integrated food-fiber systems, particularly with the expansion of crop rotations and integrated crop and livestock systems. As just one example described in the book Fibershed, farmers grew 56 million acres of wheat in the US in 2015, most of it in the winter months. By integrating a summer hemp crop into this system, the United States could produce 23 billion one-pound garments annually, without converting any additional land to agriculture. This would provide more textiles than the US currently consumes in a year.

Valley Oak Mill Fibershed. Image credit: Paige Green

Investing in Transformation

Finally, both natural and synthetic fibers all too often feed into an extractive global textile industry that has been designed to favor the interests of multinational textile and apparel conglomerates, chase the lowest prices wherever they can be found around the globe, and bury the resulting labor and environmental exploitation beneath layers of opaque contractors and subcontractors. As historian Matthew Desmond notes, "many of us who are vested in multinational textile companies today are unaware that our money subsidizes a business that continues to rely on forced labor in countries like Uzbekistan and China and child workers in countries like India and Brazil.”

Because textile crops require substantial processing to move from fiber to finished good, shifting this global system requires the capitalization of just, equitable, and transparent natural fiber milling and manufacturing systems. We urge funders and investors to consider the fiber and textile system as an extension of their efforts to support agriculture that is truly “regenerative.” We acknowledge that this term draws on indigenous wisdom that goes far beyond a set of cropping practices to call for a rethinking of the fiber and textile system’s impact on communities and livelihoods as well. As food justice writer Eric Holt-Jimenez noted recently, “The belief that we will change things through individual market choices is a way of not questioning the market itself.”

Reshored, relocalized, and reconnected US fiber and textile processing offers a way to connect rural and urban communities while restoring ownership of the means of production to farmers, communities of color, and rural communities across the country. As just a few examples, the 12 fiber system Case Study businesses featured in the Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems Funders (SAFSF) Fibers Roadmap report offer concrete and actionable opportunities for funders and investors, while Fibershed’s Regional Fiber Manufacturing Initiative (RFMI) has mapped the needs of dozens of additional opportunities in the Western US.

Through our current work, we are also developing aligned efforts to create opportunities for funders and investors to play an active role in reforming the fiber and textile system. Fibershed is building a ground-up movement of fiber farmers, ranchers, and supply chain businesses, and has launched the RFMI to support the kinds of infrastructure revitalization described above. The SAFSF Fibers Roadmap drew on 60 national interviews with farmers, supply chain businesses, brands, and funders/investors to create a seven-year Roadmap of the kinds of integrated philanthropic and investment capital needed for systems change. Together, we are aligning our efforts to launch the development of a $5M+ integrated capital fund to help catalyze fiber system revitalization in the US and overcome specific known bottlenecks in prototyping, collateralizing loans, and more.

As investors and funders across the spectrum of capital seek new ways to deploy capital for more just and sustainable ends, we see a compelling opportunity to shift capital from the global extractive textile industry to emerging soil-based regional textile economies in the US We invite you to join us in these agricultural acts.