Chhota-Nagpur Dry Deciduous Forests

The ecoregion’s land area is provided in units of 1,000 hectares. The conservation target is the Global Safety Net (GSN1) area for the given ecoregion. The protection level indicates the percentage of the GSN goal that is currently protected on a scale of 0-10. N/A means data is not available at this time.

Bioregion: Indian Dry Deciduous Forests (IM3)

Realm: Indomalaya

Ecoregion Size (1000 ha):

12,269

Ecoregion ID:

292

Conservation Target:

7%

Protection Level:

9

States: India

The Chhota-Nagpur Dry Deciduous Forests ecoregion still harbors large populations of Asia’s largest predator and herbivore, the tiger and Asian elephant, both of which are still able to roam the landscape with relative freedom, a rarity in this bioregion.

The Chhota-Nagpur Plateau, itself composed of three smaller plateaus, also has pockets of vegetation with endemic plants. In the geological past, the plateau formed the bridge between the Satpura Hill Range that extends westwards along the Indian Subcontinent and the Himalaya, allowing an exchange of species adapted to a montane climates.

These plateaus have ancient origins dating back to Gondwanaland. Geologically, the plateau is composed of Precambrian rocks more than 5.4 billion years ago. Coal deposits are now being mined. A number of streams have now been incised into the plateau, creating a series of valleys and hills.

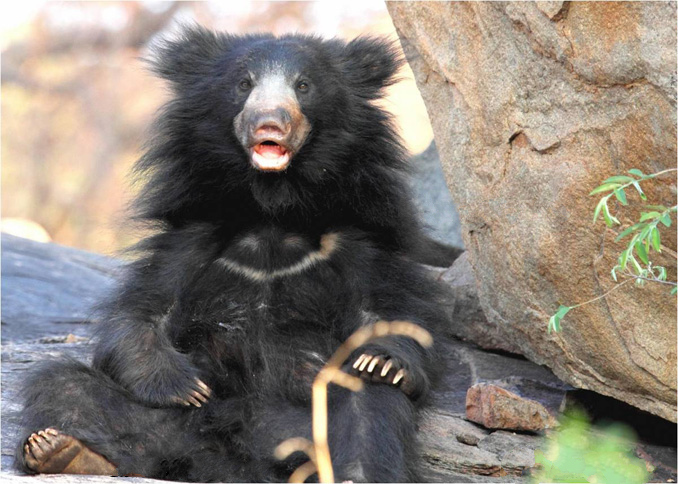

The flagship species of the Chhota-Nagpur Dry Deciduous Forests ecoregion is the sloth bear. Image credit: Creative Commons

The climate is seasonal. Winters are cool and nighttime temperatures can drop below freezing in some places. Summers are warm, with temperatures reaching 35ºC but not as hot as in the plains below, which can exceed 40ºC. A rainy season from June to September brings around 1,400 mm of rainfall.

Because the Chhota-Nagpur Plateau receives less rainfall than the adjacent areas the vegetation is drier, and the ecoregion represents the dry deciduous forests on the plateau. The major trees are Sal, or Shorea robusta, with other species in genera such as Anogeissus, Terminalia, and Lagerstroemia that are usually found in Asian dry deciduous forests. Twisted lianas drape the trees in denser forests. The ecoregion has a few endangered, endemic species, notably Aglaia haselettiana, Carum villosum, and Pycnocyclea glauca.

The fauna is not exceptionally distinctive from the adjacent ecoregions. The mammals comprise of 77 species, and none are endemic. However, they include several of India’s charismatic species, including the tiger, Asian elephant, wild dog, sloth bear, four-horned antelope or chousingha, blackbuck, and Indian gazelle or chinkara.

The bird fauna is more diverse, with almost 280 species, although again, none are endemic to the ecoregion. Notable species of conservation importance are the globally threatened lesser florican, and two hornbills, Indian grey hornbill and oriental pied-hornbill. The hornbills, in particular, need large, mature trees for nesting. The female hornbill will stay inside the nest until the eggs hatch. The nest entrance is ‘walled up’ with the exception of a small opening through which the male will feed the female during this time. Hornbills are also ‘landscape architects’ in that, after eating fruit, they disperse seeds far from the mother tree and thus shape the forest composition.

Indian grey hornbill. Image credit: Creative Commons

Most of the forests in the ecoregion have been cleared, and livestock grazing has contributed to degradation. Extensive areas are also mined for iron ore and coal, disrupting ecological connectivity. There are 13 protected areas, with Sanjay and Palamau being larger than 1,000 km2 that provide important core habitat for the large vertebrates in this ecoregion, especially in the northern areas where intact forests still remain.

Given these threats, the priority conservation actions are to: 1) restore and rehabilitate degraded mine sites along important corridors that are critical to the migration and dispersal of elephants and tigers, and can contribute to the ecological integrity of the ecoregion; 2) protect the areas that harbor endemic flora; and 3) engage local stakeholders to promote more sustainable practices of livestock grazing and other resource extraction activities.

Citations

1. Wikramanayake, E, E. Dinerstein, et al. 2002. Terrestrial Ecoregions of the Indo-Pacific: A Conservation Assessment. Island Press.

2. Johnsingh, A.J.T., Pandav, B. and Madhusudan, M.D., 2010. Status and conservation of tigers in the Indian subcontinent. In Tigers of the World (Second Edition) (pp. 315-330).

3. Mani, M.S. ed., 2012. Ecology and biogeography in India (Vol. 23). Springer Science & Business Media.