How rewilding just 20 species can restore ecosystems across almost one-quarter of the Earth’s land

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Mammal Assemblages

- Species Rewilding

- Ecosystem Restoration

- Wildlife

The reintroduction of gray wolves to Yellowstone National Park in 1995 triggered a cascade of knock-on effects. The wolves kept herbivores like elk in check and on the move, reducing their browsing pressure on young trees. As a result, groves of willow and aspen sprouted along watercourses, creating ideal conditions for a thriving beaver population. The busy beavers in turn engineered wetlands where a diversity of fish, songbirds and invertebrates flourished. In short, the return of the top predators transformed the U.S. national park into a biodiverse, fully functioning, carbon-sequestering ecosystem.

Now, a new study suggests that restoring just 20 large mammal species to their historic habitats could similarly revitalize ecosystems and boost biodiversity across almost one-quarter of the Earth’s land area.

The international team of researchers behind the study assessed global opportunities for the restoration, reintroduction and rewilding of intact large mammal assemblages across the world’s terrestrial ecoregions, geographic areas characterized by similar plant and animal communities. They published their results in the journal Ecography.

In addition to the seven predators and 13 herbivores identified as key focal species, the researchers highlight the 30 high-priority ecoregions where large mammal rewilding is most feasible and would lead to the most significant biodiversity gains.

“There are opportunities not only in the wilderness of Amazonia or the remote Arctic, but also in dry forests or in deserts,” Carly Vynne, study lead author and program director of the biodiversity and climate team at U.S.-based NGO RESOLVE, told Mongabay. “There’s really an opportunity to conserve these unique and amazing [large mammal] assemblages in all sorts of places.”

A critical decade for nature

Large mammals, ranging from apex predators like the Yellowstone wolves to medium-size carnivores and herbivores, play vital roles in the environments they inhabit. They influence everything from the behavior of other animals in the food chain to the diversity and structure of vegetation, and the abundance of rodents and invertebrates.

Moreover, studies have found that areas with intact large mammal assemblages typically store more carbon. And by preying on animals in poor physical condition, large predatory mammals reduce the prevalence of pathogens in their environment, thereby reducing the likelihood of pandemics.

Restoring complete large mammal assemblages to areas where they’ve been lost due to habitat destruction or overhunting adds a critical missing dimension to area-based conservation targets being considered under the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Post-2020 Biodiversity Framework, according to the study.

Such goals as the 30 by 30 initiative, whereby countries have pledged to protect 30% of their land area by 2030, should include directives for species reintroduction, according to rewilding advocates. Experts are also calling on wildlife recovery to be incorporated into the U.N.’s Decade on Ecosystem Restoration 2021-2030 to ensure full ecosystem integrity conservation worldwide.

“We can set aside habitat, but if we’re doing it in places where the wildlife has been depleted or defaunated … we’re just setting aside scenery,” study co-author Eric Dinerstein, director of the biodiversity and wildlife program at RESOLVE, told Mongabay. He said restoration efforts must be “ecologically based” and involve not just planting the native trees that used to be there, but also returning the animals that have gone extinct. “We have to really focus on bringing back those key elements of the ecosystem: the landscape engineers like rhinos and elephants, and the top predators: the tigers, lions, jaguars, polar bears, grizzly bears,” he said.

Priority species and areas for conservation

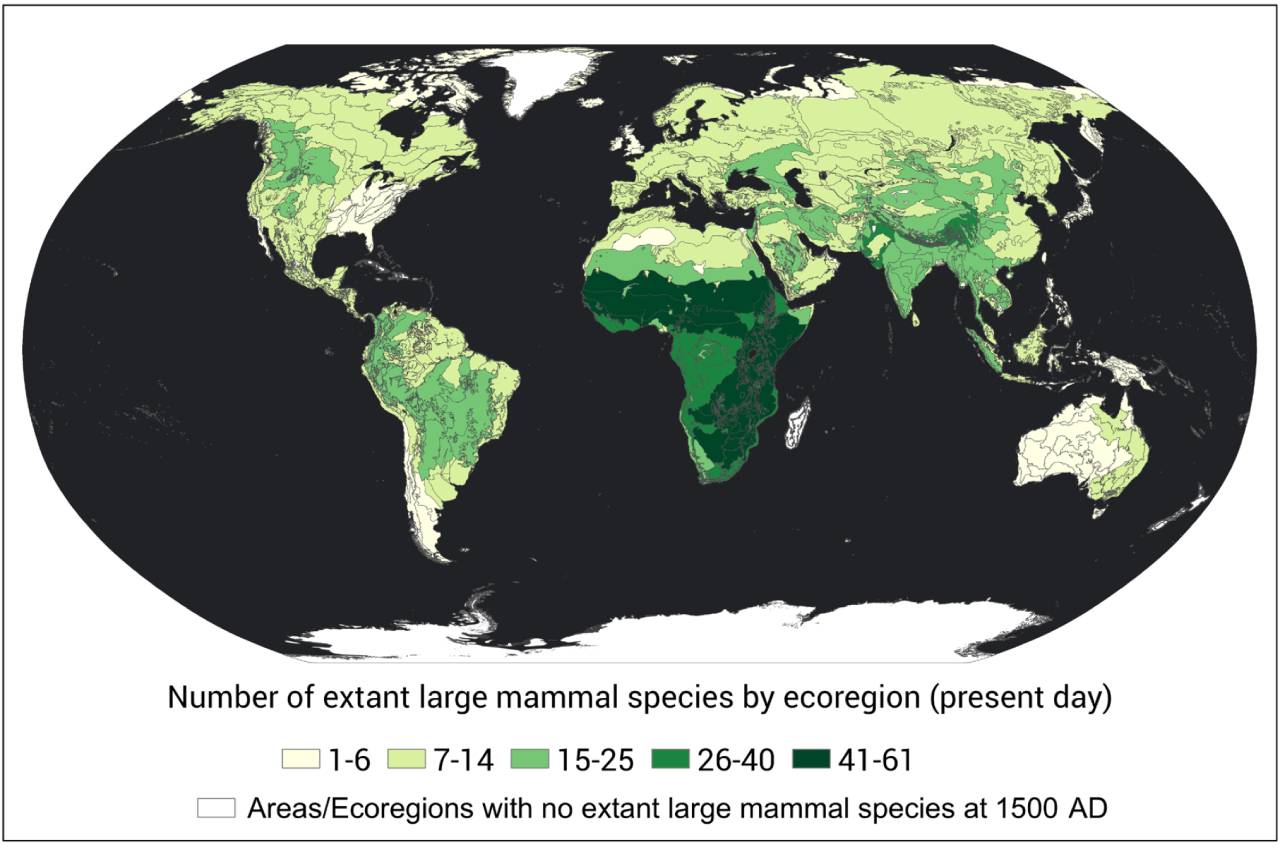

For their study, the research team first set out to establish where intact large mammal assemblages can still be found on Earth. They compared present distribution data for 298 species with estimates of where the animals lived in the year 1500, finding that just 15% of the world’s land area still supports complete assemblages.

Most of these areas are safeguarded by virtue of their inaccessibility or through direct protection and conservation. For instance, intact assemblages were found in remote boreal regions, in landscapes stewarded by Indigenous communities in the Amazon and eastern Africa, and also in parts of Asia, Europe and the western U.S. where intensive conservation measures have proven effective.

“We should consider what’s going right in those places, and look to cases where restoration has happened and it’s been successful,” Vynne said.

Next, the researchers calculated that restoring just 20 of the 298 large mammal species to their historic ranges would boost coverage of complete large mammal assemblages from 15% of Earth’s land area to 23% — a range increase of more than 11 million square kilometers (4 million square miles). Nine of the species are globally threatened; seven are predators, including jaguars, wolverines and pumas; and 13 are herbivores, such as Pampas deer, hippos and gazelles.

Finally, they looked at where large mammals could be feasibly restored within the next five to 10 years by examining ecoregions missing just one to three of their historic large mammal species. From these areas, they pinpointed 30 high-priority ecoregions where recovery efforts are underway or where sufficient habitat remains to accelerate rewilding over the next decade. A total of 16 of these priority regions require only one species to complete their large mammal assemblages.

Present species richness of large mammals by ecoregion. Map from Vynne et al. (2022) via Creative Commons (CC BY 3.0)

Read the full article on Mongabay.

Download Report