Chilean huemul: the Patagonian deer and lover of freezing weather

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Iconic Species

- Wildlife

- Mammals

- Andes Mountains & Pacific Coast

- Southern America Realm

One Earth’s “Species of the Week” series highlights an iconic species that represents the unique biogeography of each of the 185 bioregions of the Earth.

Known by many names, wümul is what the local Mapuche call this deer because it dwells in cold weather (mülm’llün) and is active right at dawn (wün). The pronunciation of the name by Spanish-speaking colonizers is huemul.

In English, it’s called the South Andean deer, and its scientific name is Hippocamelus bisulcus. Regardless of title, the Chilean huemul is an essential grazer in its ecosystem, helping prune and spread the seeds of new vegetation across Patagonia.

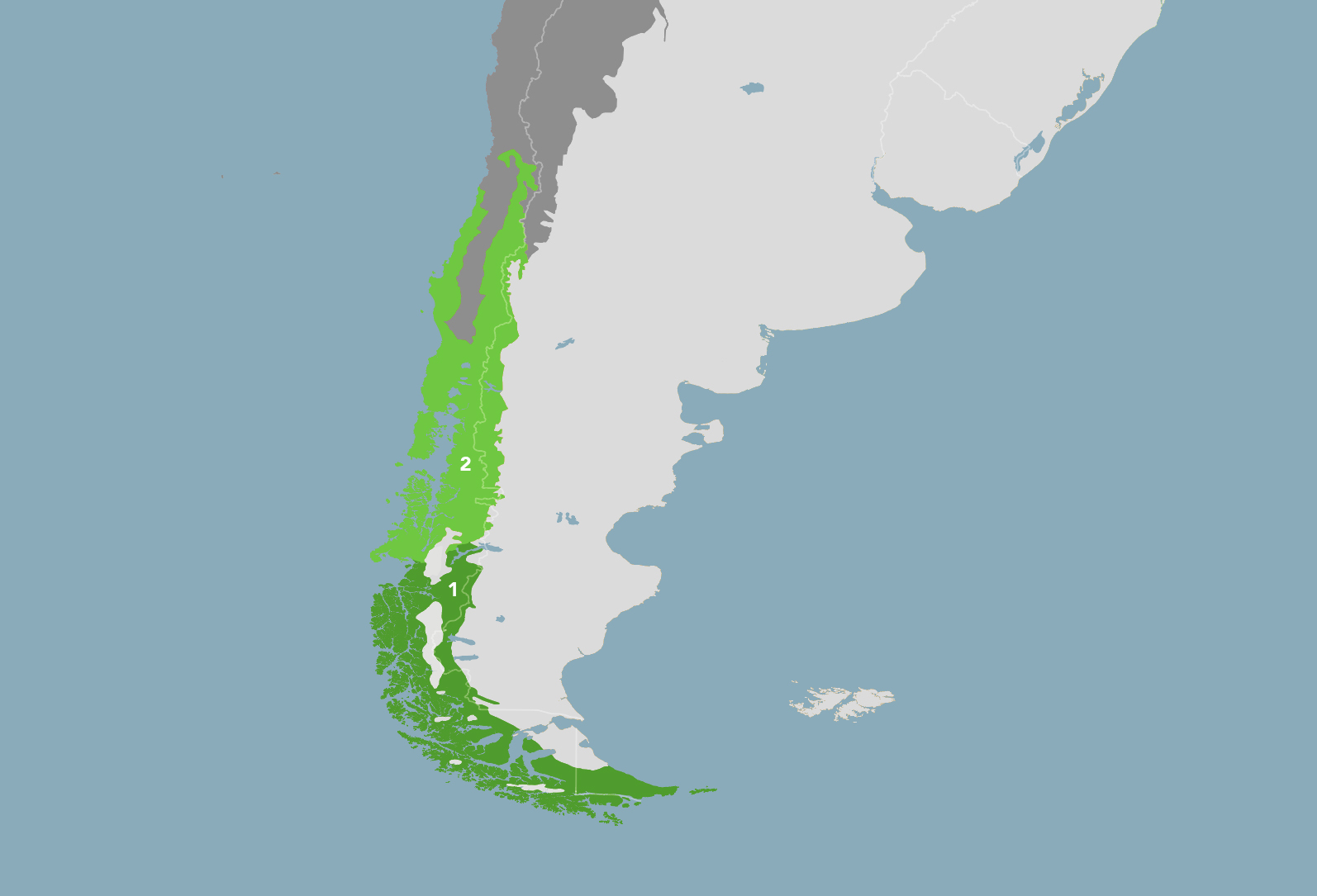

The Chilean huemul is the iconic species of the Chilean Mixed Forests Bioregion (NT1).

Life in the Patagonia landscape

The wide range of the huemul across the Andean Patagonia landscape is remarkable. Throughout the Valdivian Temperate forests and the Subantarctic Southern Beech forests, clusters of huemuls can be seen low along the coastline and high in the mountains at an altitude of 3,000 meters.

Their habitat is similar to postglacial times. Evergreens, grasses, and shrubs along the steppes surround rocky outcrops, glaciers, and large lakes.

Changing colors and binocular vision

A medium-sized deer, the huemul has a robust, short-legged body. Its average height is 1.7 meters, and females are about the same size as males. The coat of the huemul is dense, coarse, brittle, and relatively long and changes color with the season.

Between spring and autumn, the tone is a rusty brown to dark coffee, and as colder temperatures arrive, it becomes lighter in color and also thicker. This winter appearance makes the huemul less conspicuous in the barren landscape.

Underparts of the tail, the inguinal area, and the interior of the ears are white, as are small areas around the eyes and mouth. The position of the eyes gives it the benefit of a wide range of monocular vision on each side of its body at 285° and binocular vision, having only a narrow blind spot just behind it.

The distinct ‘Y’ muzzle marking

Males have a Y-shaped black pattern along their forehead and muzzle. A male begins to grow antlers for the first time at six months old, and these continue to grow as simple unbranched spikes into the winter when they become covered with velvet-like skin.

In spring, these peel off and fall at the break of the winter. After that, the cycle of regrowth of bone tissue and later casting runs for less than half a year every year.

Power in numbers

From spring to early summer, when females care for their fawns, they remain segregated from their typical group, occupying rugged terrains along the eastern-facing slopes of the Andean Cordillera. This rough topography allows the fawn to stay hidden and away from predators such as foxes. Such a strategy is convenient while the youngsters develop locomotor skills.

As autumn returns, females and their young return to the group to spend the winter together. This aggregation of males and females almost year-round is considered by experts to be unusual among other ungulates. Yet, it can be explained in that they provide each other with protection and care.

A diet of over 145 plant species

A grazer, the huemul feeds on leaves and flowers of herbaceous and bush plants in summer and autumn. In winter and spring, it relies on green buds from trees such as the southern beech tree (Nothofagus).

The huemul prefers the beech tree forests for their low understory vegetation that allows for agile foraging. The canopy also protects the animals from direct radiation in summer and keeps predators like the puma and the culpeo fox at bay.

Its favorite flowers are those of the Andean fire bush (Embothrium coccineum). Studies have shown that the huemul feeds on over 145 different plant species, making them essential to their ecosystem as they help create new life through the dispersal of seeds.

Interestingly, the huemul avoids grasses despite the abundance in the steppes. Biologists say this preference is because grasses have a high content of silica dust that would abrase their molars if continuously consumed.

Threats of stress and fragmentation

When huemul populations are exposed to stress, there is less breeding activity, and fawn survivorship is very low. In Nahuel Huapi National Park in Argentina, tourism and the invasion of the introduced red deer (Cervus elaphus) are driving the huemul cluster there to total extinction.

In the Nevados de Chillán, the farthest north in Chile where they can be found, huemul populations are fragmented and isolated. This separateness makes them more susceptible to becoming extinct by the action of hunters, the attack of natural predators, and the expanding presence of sheep and cattle, as diets are similar.

Conservation success

The good news is that when populations are undisturbed in their natural habitat, clusters of fifteen to twenty animals can increase five to sevenfold in twenty years. Such is a reported case at the Cochrane Lake area in the Aysén District in Chile, where the National Huemul Corridor was created through the rewilding program of Doug and Chris Tompkins.

The Tompkins' ongoing effort is significant, considering that fewer than 2,000 huemul deer remain worldwide.

Protecting free spirits

In Chile, there are thirteen national parks and reserves where the huemul is protected, while in Argentina, there are twelve. However, another hurdle in safeguarding the huemul is its free spirit, as it enjoys roaming with no man-made structures to keep it secluded.

A decade ago, it was reported that only a third of the 101 identified huemul clusters were occupying any of these national parks, over a third were entirely outside, and the remainder were only partially ranging the protected areas.

Among the priority conservation actions for the huemul are promoting the creation of private protected areas that facilitate connectivity, offering training programs to improve local wildlife management, and encouraging education activities and media campaigns.

One such effort was made by El Mercurio newspaper in 2017 through infographic material and a 3D image of the huemul. Awareness such as this helps spark interest in the species with the ultimate goal of including more locals in conservation efforts to protect this fascinating deer only found in Patagonia.

Interested in learning more about the species of Southern America? Use our interactive navigator to explore the bioregions of the world.

Launch Bioregion Navigator