The grizzly bear: Surprisingly, the world's most flexible large mammal

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Iconic Species

- Wildlife

- Mammals

- Northern America Realm

- American West

One Earth’s “Species of the Week” series highlights an iconic species that represents the unique biogeography of each of the 185 bioregions of the Earth.

Grizzly bears (Ursus arctos horribilis) are exceptionally well suited to fill the role of apex predator. They are big and versatile, powerful and smart, and, when the need arises, fierce. But Grizzlies are also on the Endangered Species list, and their future depends less on their natural prowess and more on whether humans give them the freedom to roam across the wilderness they need to survive.

But their future seems always to swing between hope and doubt. In North America, no apex predators other than wolves evoke a greater spectrum of responses—from fear and loathing on one end to respect and admiration on the other.

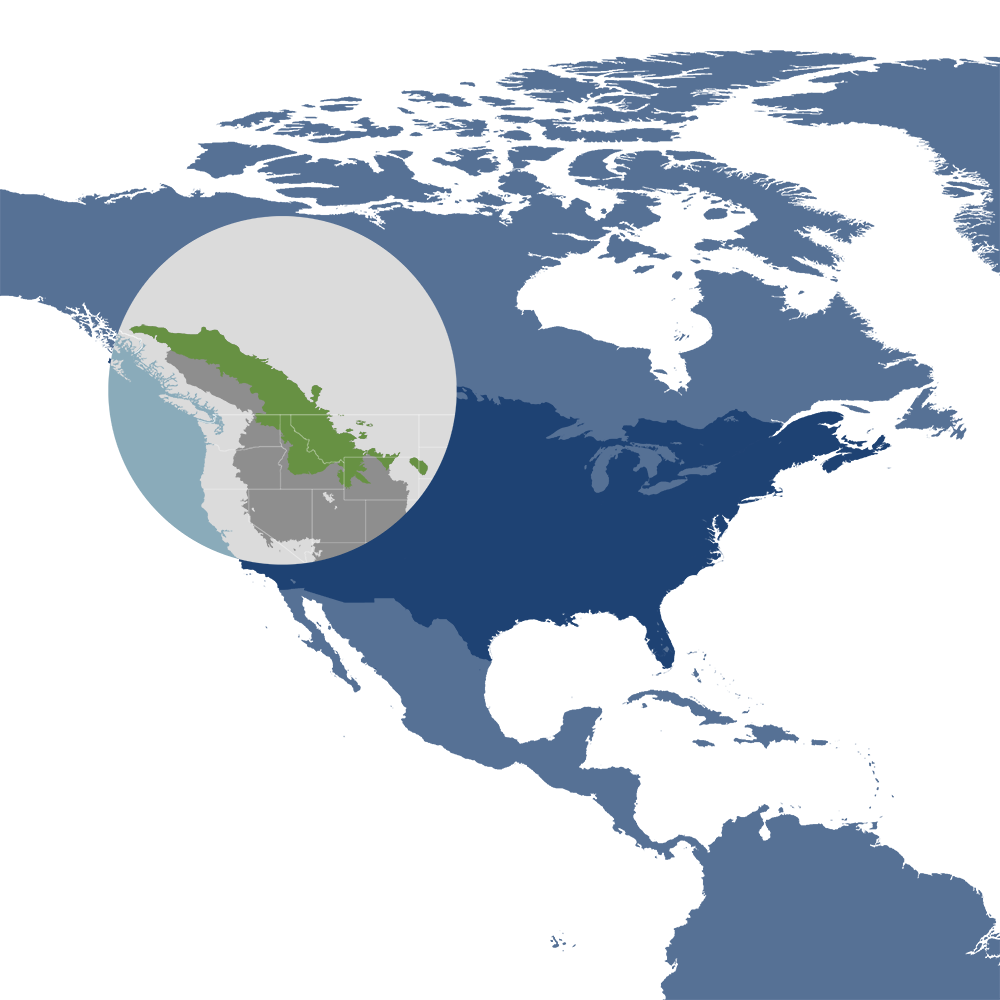

The grizzly bear (Ursus arctos horribilis) is the iconic species of the Greater Rockies & Mountain Forests bioregion (NA13) located in the American West subrealm in Northern America.

Exploring the grizzly’s range and classification

Grizzly bears are a subspecies of the brown bear, Ursus arctos. As the scientific name implies, brown bears occur across the Northern Hemisphere, from the Mediterranean countries in Southern Europe to Scandinavian countries in Northern Europe, from Tibet to Russia (with a rare subspecies in the Gobi Desert), and from Alaska to Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho.

The brown bears in North America are a subspecies classified Ursus arctos horribilis, a.k.a. the grizzly bear.

Physical characteristics and evolutionary adaptations

Grizzly bear adults are about one to 1.2 meters at the shoulder (3-4 ft). They can weigh 110 kilograms (250 lb), as in the case of a small female in the Rocky Mountains, to about 816 kilograms (1,800 lb) in the case of very large males on the Alaska Peninsula and on Kodiak Island (where the second subspecies in North America, Ursus arctos middendorfii, is found).

Grizzly bears can sometimes be confused with black bears because Grizzlies can be black, and black bears can be brown. But Grizzlies have smaller, more rounded ears, a more squared snout, and much longer, straighter claws.

They also have a distinctive hump above their shoulders because of the powerful muscles that evolved along with their claws for digging.

Grizzly bear in Bozeman, Montana. Image Credit: Walt Snover from Getty Images Pro via Canva Pro.

Ecological versatility and surprising flexibility

Many experts think that bears were once predominantly plains animals, feeding on roots, gophers, and other grassland flora and fauna before humans drove them into the forests and mountains. This is consistent with historical observations that there were more grizzlies on the plains than in the mountains.

Yet according to Dr. Peter Alagona, a leading authority, “The fundamental trait of the brown bear is not its affiliation with a particular type of environment but rather its flexibility. Indeed, besides humans and pigs, the brown bear is almost certainly the world's most flexible large animal. Until recently, it lived in semi-arid shrublands, grasslands, wet coastal forests, temperate deciduous forests, arctic/alpine areas, coastal zones, and Mediterranean ecosystems.”

Indeed, if flexibility is a trait we share with grizzlies, it’s no surprise, for we share 80% of their DNA.

Hunting and hibernation habits

Grizzlies are omnivores who rely mostly on fruits, roots, grasses, rodents, fish, and other small prey. One male was seen by a devoted observer to eat 4,000 moths in a single day!

They’re also able to bring down elk and other herbivores by reaching speeds up to 64 kilometers per hour (40 mph). Grizzlies rely on their accumulated fat stores to sustain them through winter hibernation, during which the sows (females) give birth — usually to twins — and emerge with their cubs in the spring.

Grizzly bear mother with her cubs. Image Credit: Jillian Cooper from Getty Images via Canva Pro.

Historical decline in the American West

In 1804, when Lewis and Clark started their exploratory expedition up the Missouri and across the Rockies to the Pacific, there were an estimated 50,000 grizzlies in the Lower 48. The adventurers described seeing them across the western Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains. Grizzlies extended southward across Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico into northern Mexico.

Scientists believe California once had the highest density of grizzlies outside of Alaska, with an estimated 10,000 grizzlies throughout the state. At the time of Lewis and Clark, the Golden State had one grizzly for every eleven people.

As the human population grew across the American West, so did the persecution of grizzly bears. British, French, and American fur trappers shot them at every chance, whether they needed their meat or not.

For sport, the Spanish in California lassoed grizzlies and dragged them into corrals, where the bears were forced to fight to the death against bulls. The gold miners and pioneer settlers who followed continued to shoot, trap, and poison the bears until the last wild grizzly in California was seen in 1924, in New Mexico in 1931, in Colorado in 1979, and in Washington State in 1996.

The sport of roping California grizzly bears is dramatically illustrated in James Walker’s 1877 Cowboys Roping a Bear. Courtesy of the Fred E. Gates Collection, 1955.87. Image Credit. © The Denver Art Museum

Conservation triumphs and emerging challenges

Today, an estimated 2,000 grizzlies survive in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho. This is double the population 50 years ago before they were protected under the Endangered Species Act.

But the success of their recovery has only catalyzed new threats from trophy hunters, ranchers and politicians in Montana and Wyoming who want to delist the grizzly and turn management over to the states. If this were to happen, hunting and trapping would almost certainly be renewed.

Cultural significance and tribal advocacy

So far, attempts to delist the grizzly have failed, partly because of coordinated opposition by Native American tribes. Grizzly bears have always been central to tribal identity and culture.

A bear sculpture chipped from volcanic stone that was found in California is 7,000-8,000 years old. Most tribes had a bear dance and a bear shaman, and wearing a necklace of bear claws imbued the wearer with the power and protection of the grizzly.

Sioux chairman Brandon Sazue observed that grizzlies taught the tribes “the ability for healing and curing practices, so the grizzly is perceived as the first medicine person.”

Former chairman of the Hopi Tribe in Arizona, Ben Nuvamsa, said of the grizzly, “He is our relative. For us Bear Clan members, he is our uncle. If that bear is removed, that does impact our ceremonies in that there would not be a being, a religious icon that we would know and recognize.”

A grizzly bear cub walking free from mother bear. Image Credit: © John Morrison

Indigenous efforts to protect and rewild grizzly bears

In response to efforts to remove the grizzly bear from the Endangered Species Act, Native American tribes sued the government in 2017, and 170 tribes signed the Grizzly Treaty, advocating for protecting and restoring grizzly populations across North America. It is the most signed treaty in tribal history.

Many years in the making, a plan to rewild grizzlies back to the Northern Cascades in Washington State is nearing approval. More recently, the California Grizzly Alliance, a consortium of tribal leaders, conservationists, and scientists, has organized the recognition of the 100th anniversary of the last sighting of a wild grizzly in California, declaring “2024 the Year of the California Grizzly Bear.”

Their longer-term aspiration is to “bring the state flag back to life” by rewilding grizzlies in the state.

Scientists with the California Grizzly Alliance have completed studies on the bears’ biology and behavior in preparation for the effort. Perhaps most interestingly, they have discovered that contrary to popular belief, California grizzlies were not the fierce carnivores of lore. They had an 80% plant-based diet that relied primarily on acorns. In fact, theirs was a very healthy Mediterranean diet.

Rewilding risks, benefits, and ecosystem impacts

Any proposal to rewild Grizzlies brings with it heated debate. That’s understandable, for grizzly bears can kill people—an average of two per year since 2020. But the number of deaths is relatively small considering the bears’ wide range and the hundreds of thousands of people who hunt, fish, ranch, and recreate in their habitats. Most deaths could be avoided with better coexistence and avoidance protocols.

Against that, we must ask: what is the loss of not having healthy populations of grizzly bears? What is the loss to ecosystems where grizzly bears, as top predators who are also avid foragers, keep flora and fauna in balance and function as seed and nutrient distributors?

Research by Dr. Suzanne Simard of the Mother Tree Network illuminates the intimate relationship among salmon, bears, and healthy forests. She describes how grizzlies capture salmon and sit beneath trees to eat select portions (preferring the brain, skin and roe), leaving carcasses that feed not only other animals and organisms, but also nourish the trees. Isotope tracing shows that salmons’ nitrogen is shared far into the forest through the trees’ mycorrhizal networks.

A grizzly bear roams in a wooded area near Jasper National Park, Alberta, Canada. Image Credit: Dwayne Reilander, Wiki Creative Commons.

A radical defense of ecosystem restoration

As Kris Tompkins of Tompkins Conservation expressed it so well in Time Magazine:

We must ask ourselves a more subtle yet important question: What is the spiritual loss when a vital part of an ecosystem is missing? In the case of the grizzly, that includes the humility that comes from sharing a landscape with a creature that requires you to remember you are not always the dominant species.

Support Nature Conservation Solutions