Namib Desert

The ecoregion’s land area is provided in units of 1,000 hectares. The conservation target is the Global Safety Net (GSN1) area for the given ecoregion. The protection level indicates the percentage of the GSN goal that is currently protected on a scale of 0-10. N/A means data is not available at this time.

Bioregion: Southwest African Coastal Drylands (AT10)

Realm: Afrotropics

Ecoregion Size (1000 ha):

7,959

Ecoregion ID:

103

Conservation Target:

94%

Protection Level:

10

States: Namibia

The ingenious head-stander beetle exploits fog for water intake in one of the most arid regions in the world: the Namib Desert. The unusual behavior of fog-basking involves the beetle sitting on their head, facing into the wind collecting fog on its elytra which then runs down to its mouth. This adaptation is critical during prolonged periods of drought, and relatives of this species without such morphological and behavioral adaptations are much less likely to survive in the desert.

The flagship species of the Namib Desert ecoregion is the head-stander beetle (Onymacris unguicularis). Image Credit: Courtesy of Tim Evanson, Flickr.

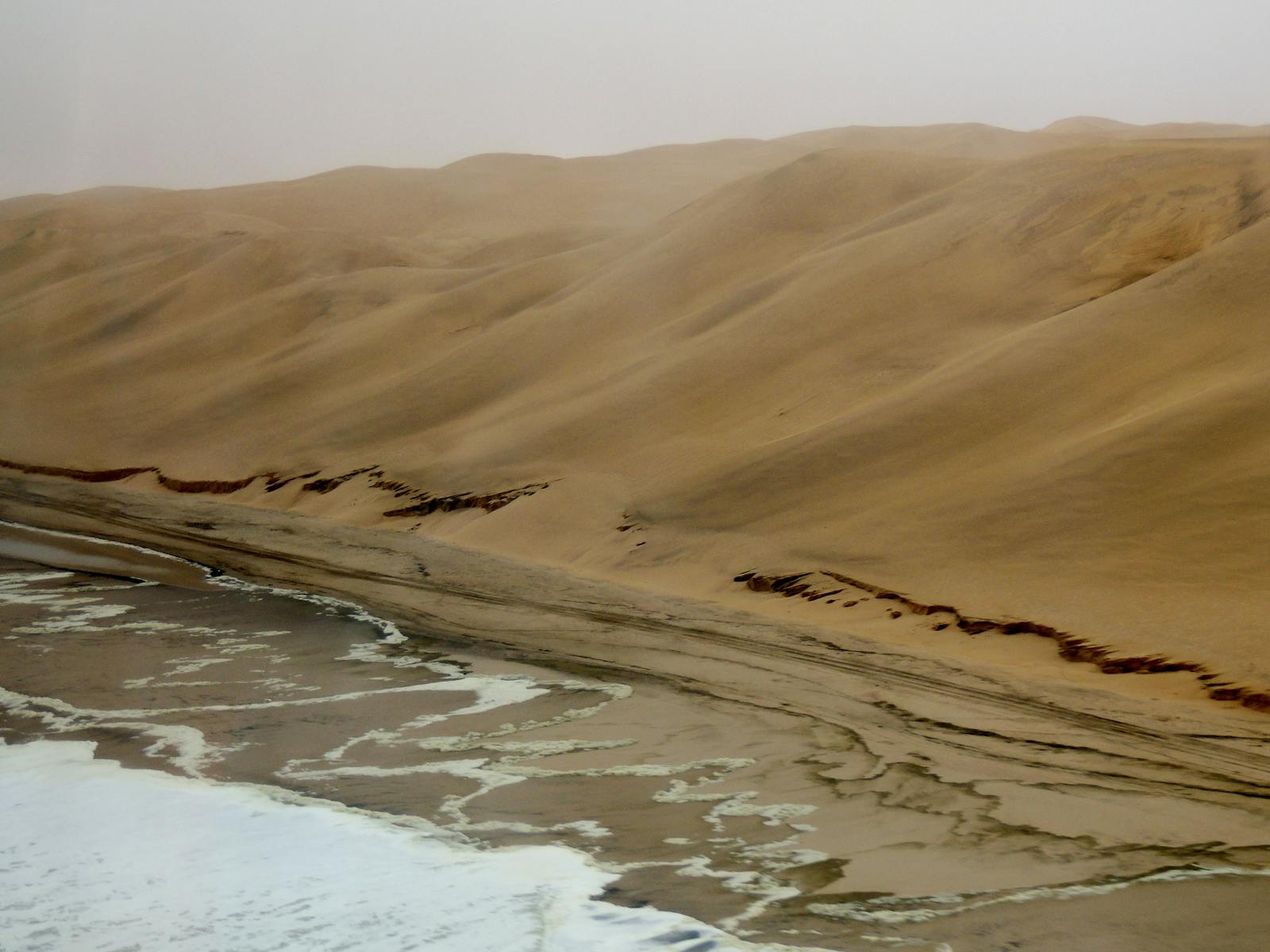

The ecoregion extends along the coastal plain of western Namibia, from the Uniab River in the north to the town of Lüderitz in the south. It reaches inland from the Atlantic coast to the foot of the Namib Escarpment, a distance of 80 to 200 kilometers (50-124 mi). The cold Benguela Current flowing along the South West African coast suppresses rainfall over the desert. However, it supplies fog up to approximately 100 kilometers (62 mi) inland. This ecoregion has sparse and highly unpredictable annual rainfall. Mean annual rainfall ranges from 5 millimeters (.2 in) in the west to about 85 millimeters (3.4 in) along the ecoregion’s eastern limits. The coastal area has a mean annual rainfall of 2 to 20 millimeters (.08-.8 in) and has thick fog for more than 180 days of the year.

Air temperatures are low because of the cool air coming off the Benguela Current. Up to about 50 kilometers (31 mi) inland, the mean annual rainfall increases from 20 to 50 millimeters (.8-1.9 in). Fog, while still important to desert organisms, occurs only about 40 days in the year. Still, further inland, fog is rare, and the mean annual rainfall increases from 50 millimeters to a maximum of 85 millimeters (1.9-3.3 in). Daily and seasonal temperatures increase sharply and become highly variable, with temperatures below 0° and above 50°C recorded (32-122°F).

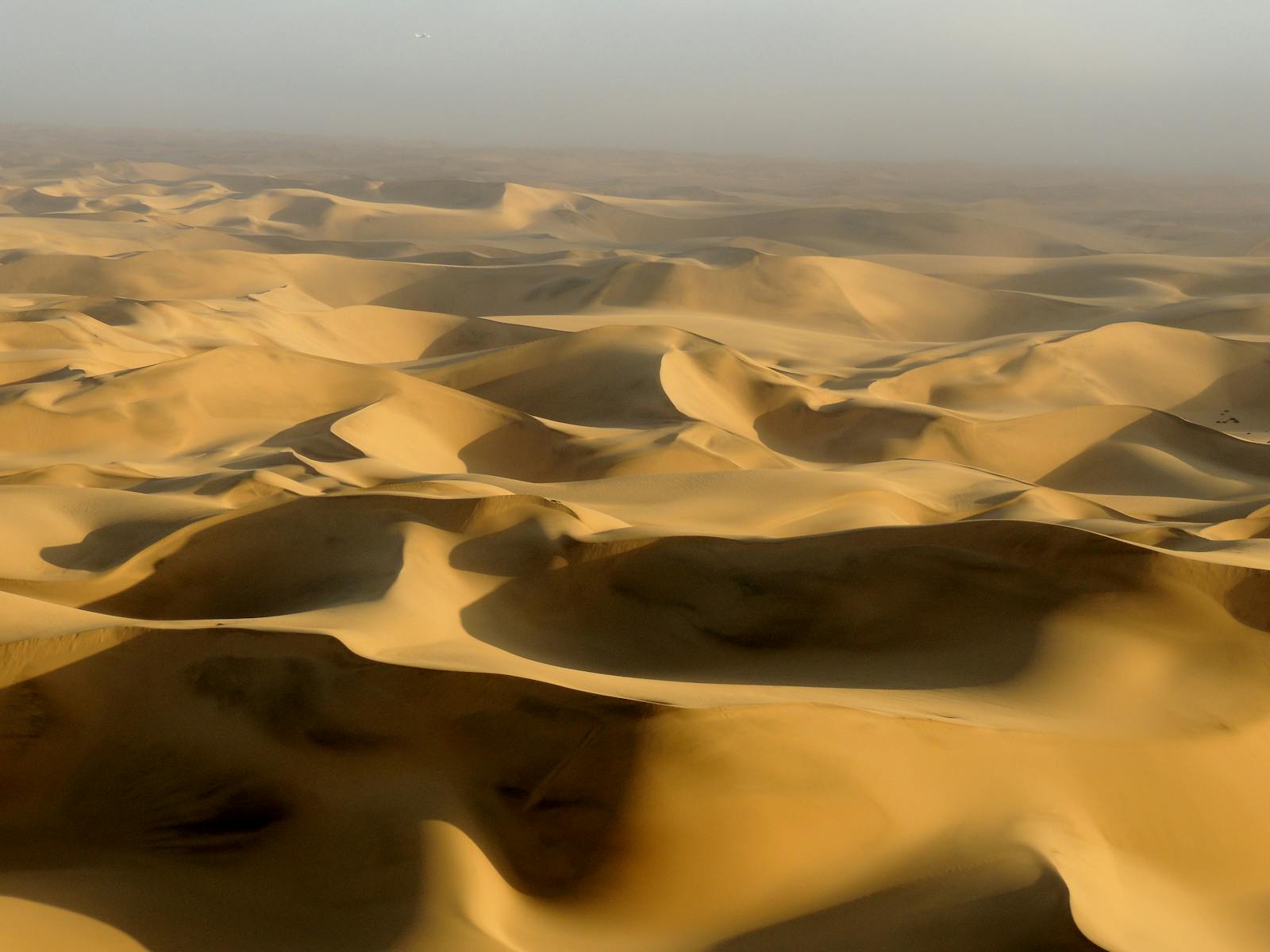

Southern Namib is an expansive area of large, shifting dunes, which reach elevations of 300 meters (984 ft). To the north of the Kuiseb River, the dunes give way to the gravel plains of Central Namib that are dotted with inselbergs of granite and limestone.

Quiver trees (Aloidendron dichotomum), Namib Desert. Image Credit: Olga Ernst, Wiki Creative Commons.

The vegetation comprises a few perennial grasses and the succulent Trianthema hereroensis. Hummocks formed by Acanthosicyos horridus occur between these sand dunes and the coast. The dunes move north, driven by prevailing southerly winds, and are brought to an abrupt halt by the vegetation of the Kuiseb River. The Central Namib contains a narrow strip of vegetation that follows the coastline north of the Swakop River, which supports shrubs such as Psilocaulon salicornioides, Zygophyllum clavatum, Salsola aphylla, and S. nollothensis. The pencil plant and dollar bush are prominent in the fog-influenced coastal belt.

The Namib Desert, isolated between the ocean and the escarpment, has been arid for millions of years. This has produced a relatively stable center for the evolution of desert species, with high levels of plant endemism and numerous adaptations to arid conditions. The monotypic Welwitschia mirabilis is endemic to the Namib and Kaokoveld Desert to the north. These plants have the longest-lived leaves of any member of the plant kingdom, with the largest plants estimated to be about 2,500 years old. The Namib Desert supports a large number of small rodent species, such as the dune hairy-footed gerbil and Grant’s golden mole. Larger ungulates are scarce in the Namib Desert, with only gemsbok and springbok normally present. Hartmann’s mountain zebra is found in the extreme east in the transition belt between the desert and the escarpment. Predators include cheetahs, brown hyenas, spotted hyenas, black-backed jackals, Cape foxes, and bat-eared foxes. Reptiles contribute much of the high faunal species richness and endemism, and have evolved adaptations to survive in this harsh environment. Some of the endemic reptiles, including the wedge-snouted sand lizard and barking gecko, dive beneath the sand to escape danger.

The Namib-Naukluft National Park is the largest conservation area in southern Africa. The Cape Cross Seal Reserve National Park is located within this area and protects one of the largest colonies of Cape fur seals in southern Africa. Other protected areas include Erg du Namib World Heritage Site, NamibRand Private Reserve, Sperrgebiet National Park, and Dorob National Park.

Gemsbok (Oryx gazella), Namib Desert. Image Credit: Thomas Schoch, Wiki Creative Commons.

A major threat in this area is off-road driving. The impact of this activity is greatest on the gravel plains where depressions left by vehicles remain for more than 40 years. Lichens are particularly sensitive to mechanical damage as they grow extremely slowly and cannot quickly repair damaged thalli. The major threat to the Namib-Naukluft Park is the drop in the water table along the Kuiseb River. This is caused primarily by the extraction of ground water at two sites near Walvis Bay, which supplies Walvis Bay and Swakopmund and the Rössing Uranium Mine nearby. Another more modest threat to the Namib-Naukluft Park is by the Topnaar pastoralists who graze large herds of goats and small groups of donkeys. The livestock have overgrazed the understory plant growth and fallen seedpods of the riverbed and are competing for food with wild animals, such as gemsbok. Mining exploration in Dorob, Namib-Naukluft, and Sperrgebiet National Parks can result in landscape alteration, contamination of soil and water, and the loss of critical habitats.

The priority conservation actions for the next decade

1) Promote the restoration of degraded areas.

2) Encourage community-based tourism.

3) Support herder establishments to allow the organization of sustainable practices to prevent over use of pastures and grazing areas.

-

-

1. Burgess, N., Hales, J.A., Underwood, E., Dinerstein, E., Olson, D., Itoua, I., Schipper, J., Ricketts, T. and Newman, K. 2004. Terrestrial ecoregions of Africa and Madagascar: a conservation assessment. Island Press.

2. Nørgaard, T. and Dacke, M. 2010. Fog-basking behaviour and water collection efficiency in Namib Desert Darkling beetles. Frontiers in Zoology. 7(23).

3. Government of the Republic of Namibia. 2014. Namibia’s Second National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2013-2022.Windhoek: Ministry of Environment and Tourism.

4. Seely, M., Kinahan, J., Kinahan, J., Klintenberg, P., León, A., Morrison, S., Roedern, C., Abraham, E., Felger, R.S., Laureano, P. and Mouat, D. 2006. People and Deserts. In Global Deserts Outlook. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme. -

Cite this page: Namib Desert. Ecoregion Snapshots: Descriptive Abstracts of the Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World, 2021. Developed by One Earth and RESOLVE. https://www.oneearth.org/ecoregions/namib-desert/

-