How a Kenyan airport is flying high on its climate ambition by tackling aviation emissions

“Nothing much can be done to reduce emissions when the aircraft is flying. Research is still ongoing on how it can be done effectively. But when aircrafts are parked at the gate, a lot can be done to curb carbon emissions,” engineer Owen Waithaka says as he looks at the airport runway from across his office.

It’s 9:00 am at the Moi International Airport in Kenya’s second-largest city, Mombasa. Across Waithaka’s office, a tug pushes a cargo aircraft.

Though not as busy as the Jomo Kenyatta International Airport in the capital Nairobi, the Moi International Airport, which recorded over 400 takeoffs and landings in August, has chosen to address an issue that was spotlighted by teen Swedish activist Greta Thunberg when she rode a zero-emissions boat across the Atlantic to attend the UN climate action summit: Aviation emissions.

This follows the installation of a ground-powered 500Kw solar power generation facility; the second of its kind in the African continent, the first one having been installed at the Doula International Airport in Cameroon, whose capacity is double that of the one at Moi International Airport.

Part of the 1560 solar panels at the airport premises.

Photo by Janet Murikira.

Waithaka, who has been working at the airport for the past one and a half years, has been supervising the maintenance of the project, which started operating on 10th May this year.

The 1,560 solar panels, each with a generation capacity of 315 watts, lie on a one-acre plot about one kilometer away from the airport. The farm has been able to provide an alternative source of power for the aircrafts.

The project is part of a campaign by the International Civil Aviation Authority ( ICAO), the United Nations body that regulates the aviation sector’s emissions. The campaign is targeting 14 countries, 12 of them in Africa and 2 of them in the Caribbean.

Emissions from the aviation sector contributed to approximately 2.4% of the global emissions in 2018. Though African aircrafts contribute just 5% of the world’s airline traffic, the continent has been on the receiving end of the ripple effects of climate change.

One of the effects was the two-month delay in the long rains in Kenya. The long rains started in the first week of May, just a few days before the solargate project was launched.

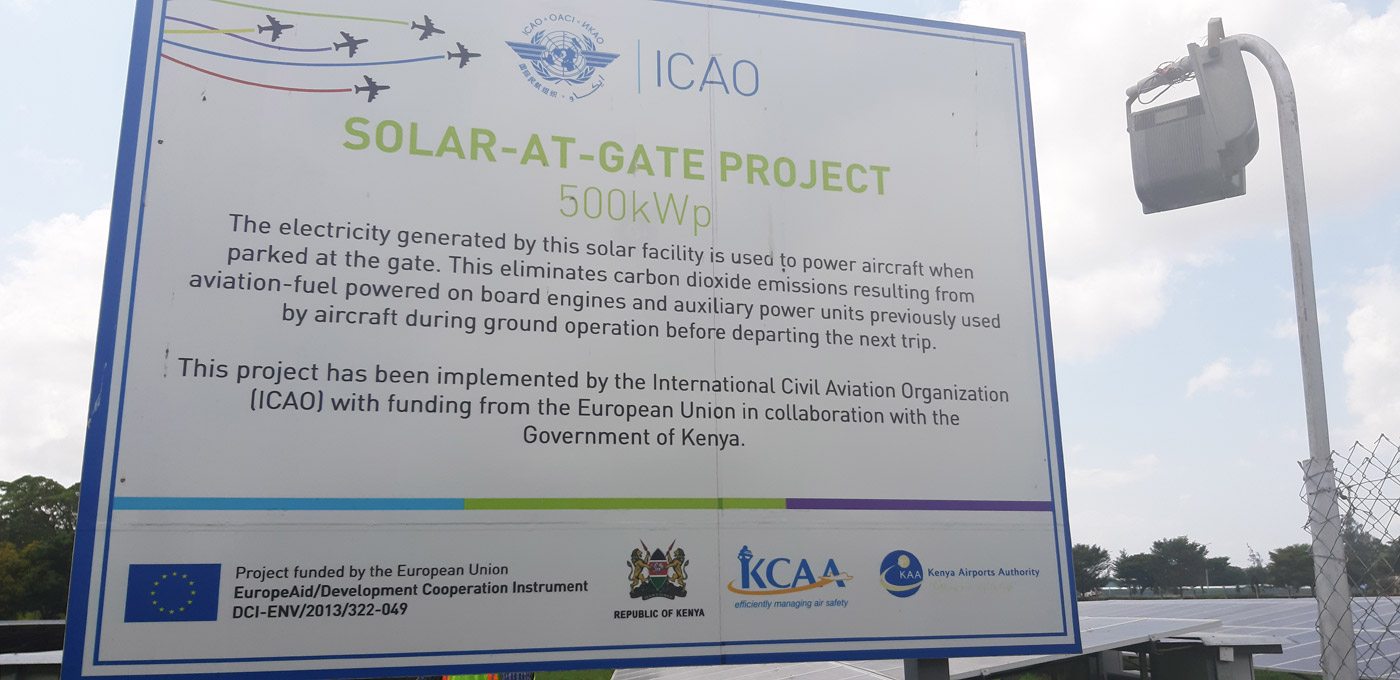

A statement about the solar project.

Photo by Janet Murikira.

Long rains normally start in the month of March in the drought-prone continent.

Despite emissions in the aviation sector being relatively low compared to other sectors, they have been a concern for most policymakers especially after a September 2019 report by the International Council on Clean Transportation, which revealed that worldwide carbon emissions in the aviation sector were rising by up to 70% faster than initially predicted by ICAO. The report says:

In Ms Thunberg’s home country of Sweden, the term Flygskam has gained popularity over the past few months as part of efforts to encourage action into curbing emissions from the aviation sector.

Flygskam which means ‘flying shame’ in Swedish has been trying to encourage travelers to reduce flying and instead take the train or other public transportation.

But how exactly does the solar project at Moi International Airport reduce emissions?

According to Waithaka, the power generated from the solar project provides preconditioned air and solar-generated electricity for the flight for its on-the-ground operations.

When an aircraft is flying, it uses its own fuel-generated power. But once its lands, it switches off its own power and starts using the power provided by the airport.

Before, the airport was using diesel-generated electricity provided by the national supplier Kenya Power and Lighting Company.

Diesel-powered generation is a leading producer of carbon emissions in the energy sector.

According to a report released by the University of Calgary, diesel-powered electricity releases approximately 2.6 kilograms of carbon for every litre of diesel burnt.

The solar electricity generated by the panels is connected to the airport power grids, thus helping substitute the diesel-powered energy from the national electricity supplier.

The electricity produced by the solar panels is not sufficient to fully power the six gates of the airport. However, since the project became operational 132 days ago, it has generated 337,225 Kwh — thus offsetting approximately 310.25 tonnes of carbon emissions.

The project, which aims to offset 1300 tonnes of carbon dioxide annually, was set up in Mombasa due to the abundant radiance of the city.

Yet, since its inception, the project has faced challenges, the biggest one resulting from climate change — the very same phenomenon it hopes to address.

The month of September, which is normally sunny, has experienced constant rain showers, with scientists predicting that rainfall will continue to be extreme in the months of October to December along the East African coast.

According to Waithaka, this means less generation of power by the facility.

All around the world, conversations on how to make the aviation sector emissions-free continue, with leading aeronautical firms like Airbus and Boeing exploring the possibility of manufacturing electric-powered aircrafts.

Though the idea always seemed like a far-fetched dream, Israeli startup Eviation proved it could be done, when, at The Paris Air Show in June this year, it debuted an all-electric flight dubbed Alice.