How the Umbanda religion saved part of the Serra do Mar Rainforest

- Nature Conservation

- Forests

- Ecosystem Restoration

- Brazil Cerrado & Atlantic Coast

- Southern America Realm

- Indigenous Tenure

In the middle of the forest of the Serra do Mar Ecological Reserve, in Santo André, Brazil, giant statues draw attention. They are representations of orixás, deities of Yoruba African culture.

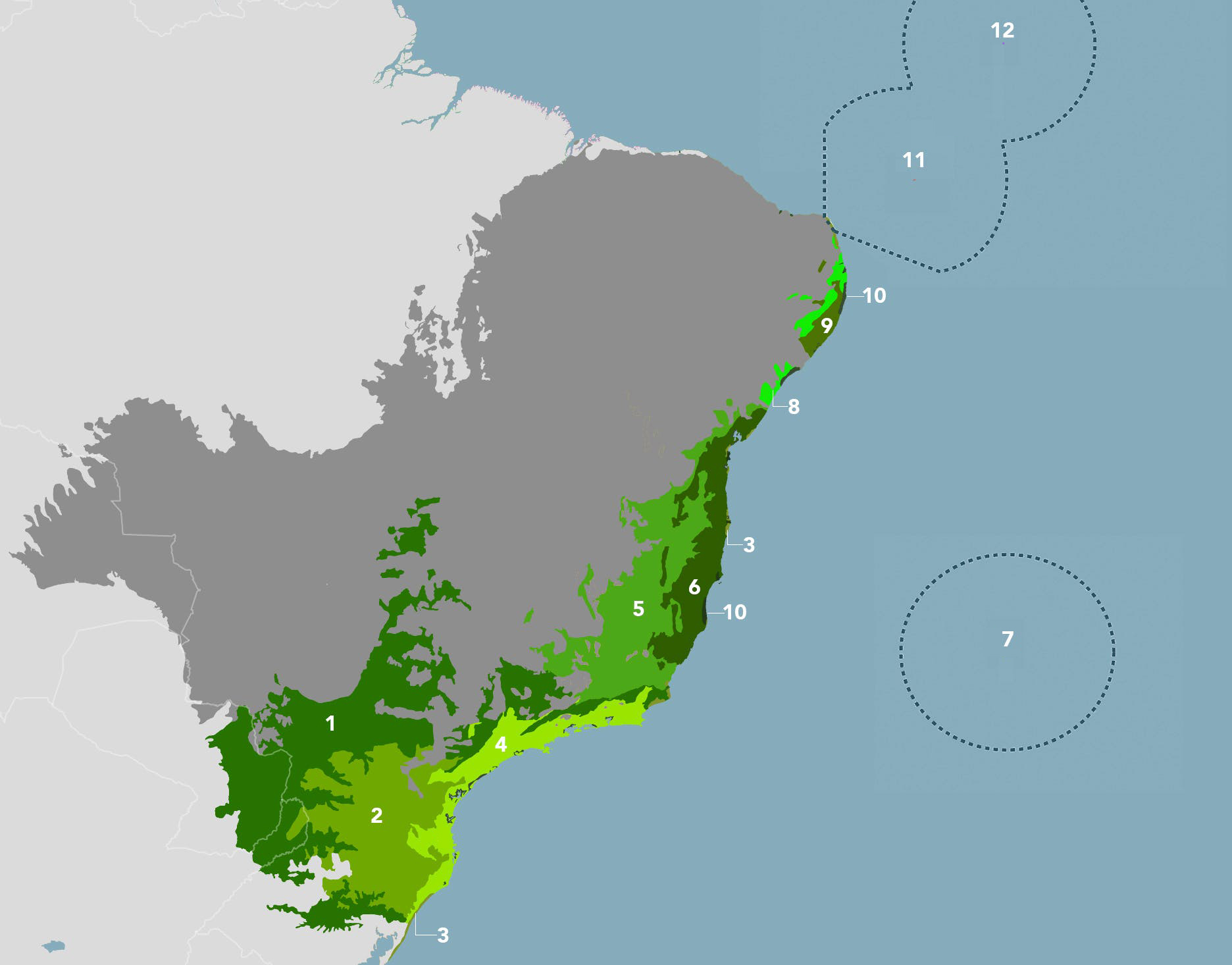

The place is the National Sanctuary of Umbanda (SANU), a Brazilian religion of African origin. It is also part of the Serra do Mar State Park, covering 332,000 hectares and the largest preservation area in the Brazilian Atlantic Moist Forests bioregion (NT14).

The Brazilian Atlantic Moist Forests bioregion (NT14) located in the Brazil Cerrado & Atlantic Coast subrealm of Southern America.

Over the past 60 years, the park has gone from total degradation to a place of environmental restoration. Followers of the Umbanda religion, who were looking for a natural place for the practices of their faith, took it upon themselves to recover the area.

Umbanda is a mixture of Catholicism, African orixás, and local Indigenous beliefs. Strongly linked to nature, each deity represents a natural element, and contact with the environment is fundamental to its followers.

“In 1960, the area was degraded due to the action of a mine, which had already been deactivated. Babalaô Ronaldo Linares, our leader, used the place to make offerings to the deity Xangô, which must be made in stone”, explains Maria Aparecida Calamari, Institutional Relations of the Umbandista Federation in the state of Sao Paulo. “But the other kingdoms were missing,” she points out.

The faithful residents of Sao Paulo, a heavily urbanized economic center of Brazil, have difficulties accessing green areas. “Babalaô Ronaldo imagined that the quarry, if recovered, would be an ideal place for rituals,” says Calamari.

The Umbanda leader took his idea to the city hall. After some difficulty getting authorization, officials allowed the project as the area was deteriorated.

Linares and his followers voluntarily began to reforest the site. Using organic material from other parts of the Serra do Mar, they gradually recovered the soil, damaged by a hard layer of dust from the extraction of stones.

Planting 30,000 native seeds, more than 645,000 square meters were reforested. Today, the park receives more than 96,000 visitors a year.

The benefits quickly started to show. With the recovery of the riparian forest and siltation removal, polluted lakes and the Pedros River are now clean.

Nature and spirituality

SANU is a successful example of the common use of conservation areas for religious practices. There are at least 60 Sacred Natural Sites (SNS) in Brazil.

SNSs are essential to some cultures, as followers believe they are endowed with a special energy. There are hallowed places to different religions in Brazil, especially Catholics, those of African origin, and the Indigenous.

Érika Fernandes-Pinto has studied Brazilian SNSs for over 20 years and holds a Ph.D. in Social Ecology. She says that governments and environmental groups need to consider cultural dimensions when considering conservation strategies, and spirituality is most important.

Integrating the physical, spiritual, and natural worlds is a core belief for all Brazilian Indigenous nations. Fernandes-Pinto sees this holistic cultural vision as positive.

She believes that there is a movement worldwide recognizing the immaterial values of the environment. The bonds of affection and belonging in nature can serve as a strong ally to biodiversity conservation and land preservation.

.webp?auto=compress%2Cformat&w=1440)