Aldabra giant tortoises: How conservation saved one of Earth’s longest-living creatures

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Iconic Species

- Wildlife

- Reptiles

- Madagascar & East African Coast

- Afrotropics Realm

One Earth’s “Species of the Week” series highlights an iconic species that represents the unique biogeography of each of the 185 bioregions of the Earth.

A living relic of an ancient world

Nestled in the remote and untouched corners of the Seychelles archipelago, a living relic from the pages of prehistoric times roams the landscape — the Aldabra giant tortoise (Aldabrachelys gigantea).

With a lineage stretching back millions of years, these colossal creatures are a testament to the resilience of life and the intricate dance of evolution. Their story is one of adaptation, survival, and a profound influence on the delicate island ecosystem they call home.

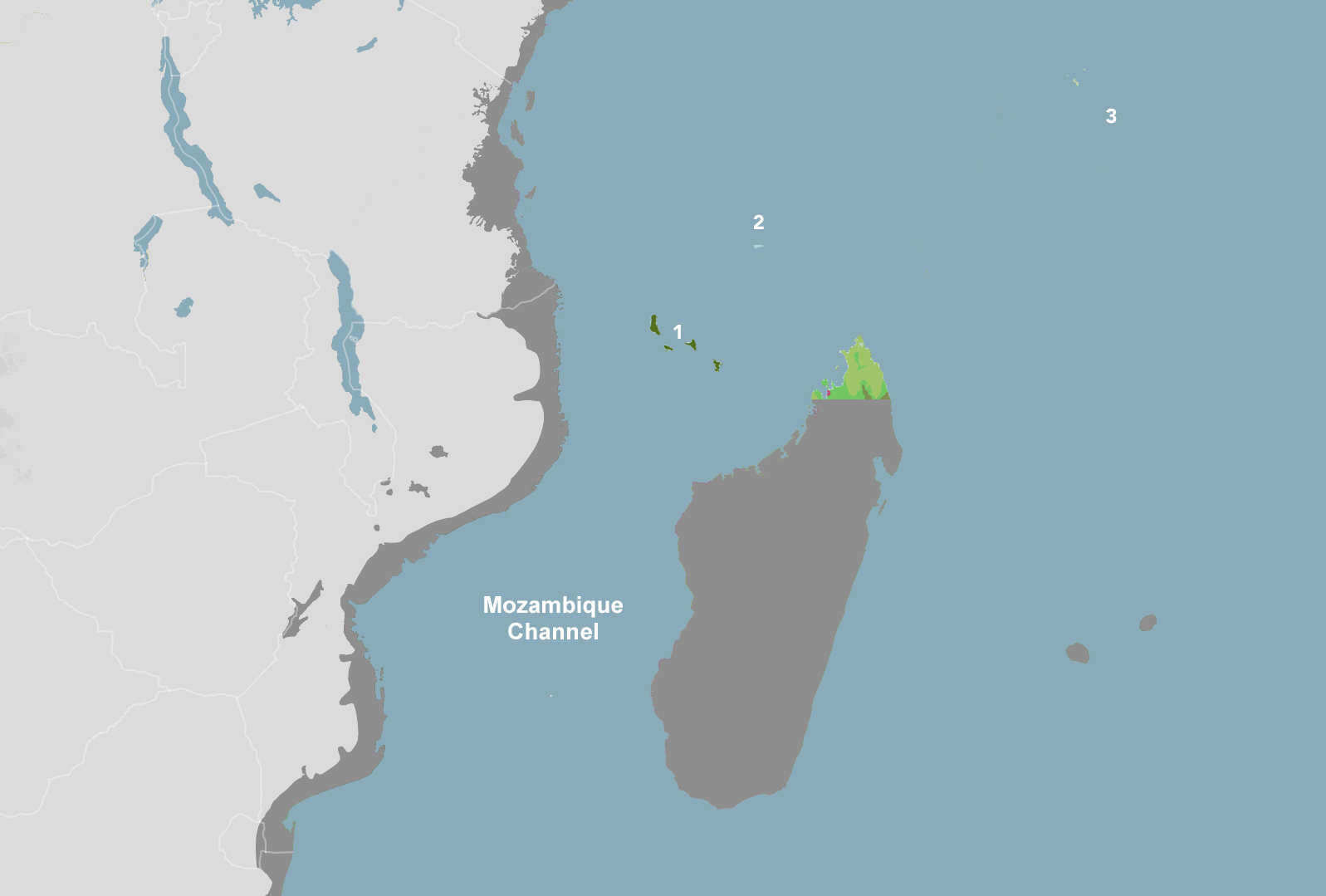

The Aldabra giant tortoise is the iconic species of the Seychelles & Comoros Tropical Islands Bioregion (AT5).

Aldabra Atoll: A sanctuary in the Indian Ocean

Once, giant tortoises were found on many islands in the Indian Ocean as well as Madagascar but were driven to extinction by European sailors' poaching and over-exploitation of their habitat.

Today, the atoll of Aldabra, an isolated realm virtually untouched by human influence, is home to the world's largest population of these gentle giants, around 152,000 strong.

Masters of adaptation

The Aldabra giant tortoise’s carapace is brown or tan with a high, domed shape. Resembling a weathered shield, it protects the tortoise’s vital organs.

Weighing up to 250 kilograms (550 lb), their stocky legs, cloaked in armor-like scales, support their hefty frame. Their necks are remarkably long, even for their imposing size, granting them access to sustenance high above the ground. This evolutionary advantage has allowed them to flourish in varied landscapes.

Grazing architects of their ecosystem

Much like African forest elephants, these heavy grazers – in both size and amount – sculpt the environment around them with their eating habits. Aldabra tortoises feed on grasses, leaves, woody plant stems, and fruit and occasionally indulge in small invertebrates and carrion. Through their droppings, they disperse seeds and, with their stomping, forge pathways for other creatures to use.

These tortoises spend mornings busily feeding and then rest in the shade when the midday heat becomes oppressive. They may submerge in pools to cool down or hunker in small caves and beneath trees. While generally solitary, during the breeding season, they congregate.

Aldabra giant tortoise. Image credit: Pixabay

Mating and the vulnerable life of hatchlings

Courtship occurs from February to May. Females lay clutches of nine to 25 eggs in nests dug 30 centimeters deep. After an eight-month incubation, tiny hatchlings emerge from October to December. Despite their intimidating size, Aldabra tortoises are incredibly vulnerable as infants. Few survive to adulthood in the wild.

A long legacy of life

Giant tortoises are among the longest-lived animals on Earth. Some individual Aldabra giant tortoises are thought to be over 200 years of age, but this is difficult to verify because they tend to outlive their human observers.

As of 2022, Esmeralda, an observed Aldabra giant tortoise, is an astonishing 179 years old.

The power of habitat conservation

While the Aldabra giant tortoise is still classified as Venerable in conservation status, it is an achievement compared to their giant tortoise cousins no longer in existence. This standing is thanks to the Aldabra Atoll being named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1982.

This protection safeguards over 35,000 hectares and is a refuge for over 400 endemic species and subspecies, including vertebrates, invertebrates, and plants. It’s a testament to the impact that conservationists, scientists, and governments can have when they work together to save nature.

A vision for a flourishing future

As ecosystems worldwide are unraveling due to the duel crisis of climate change and biodiversity loss, the story of the Aldabra giant tortoise stands as a symbol of our shared responsibility. Through collaborative conservation and vigilant protection of habitats, we can save species so that they may continue to roam the Earth for generations to come.

Explore Earth's Bioregions.jpg?auto=compress%2Cformat&w=1440)