How the Hartmann's mountain zebra got its stripes

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Iconic Species

- Wildlife

- Mammals

- Southern Afrotropics

- Afrotropics Realm

One Earth’s “Species of the Week” series highlights an iconic species that represents the unique biogeography of each of the 185 bioregions of the Earth.

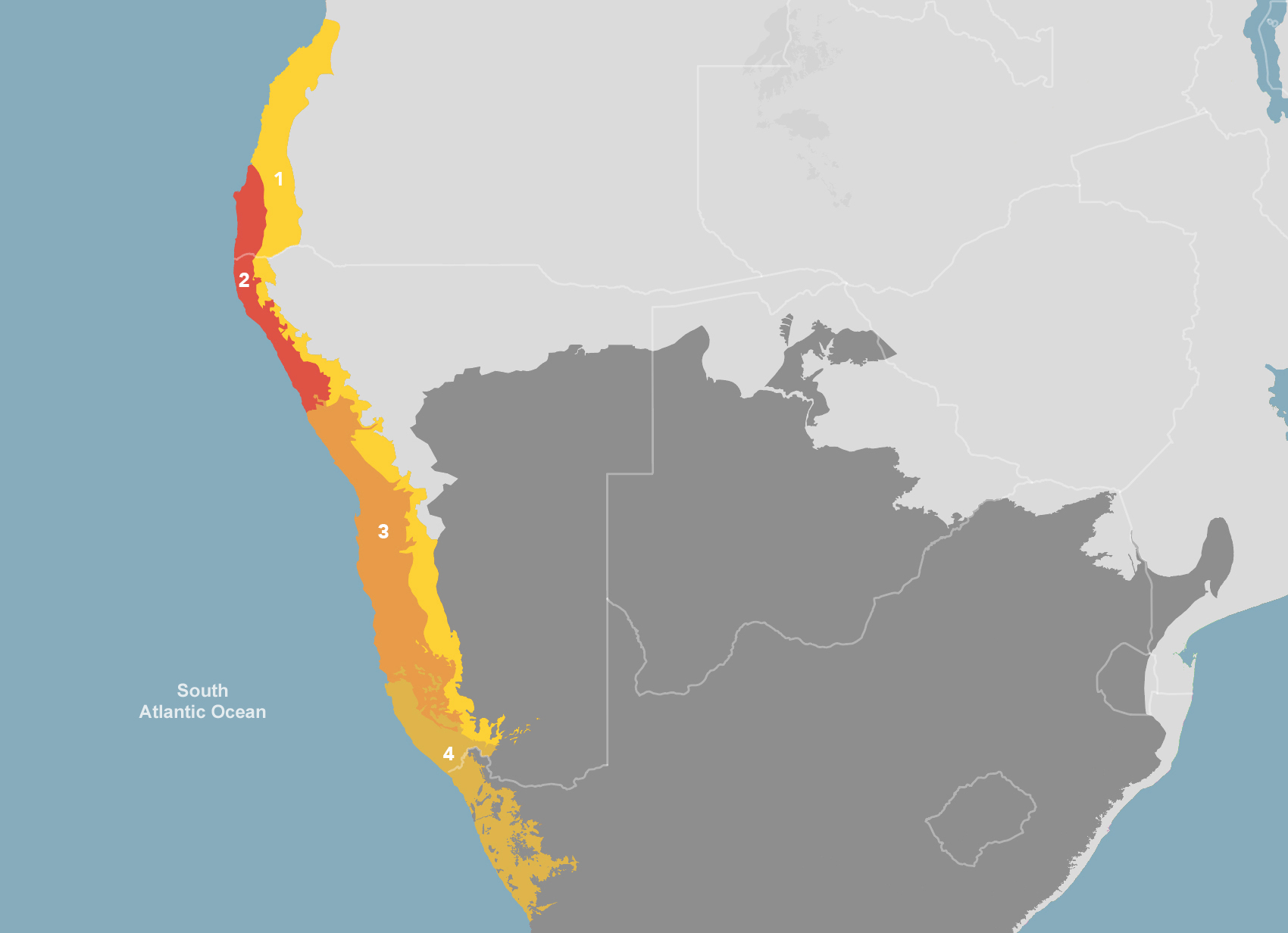

The Hartmann’s Mountain Zebra (Equus zebra hartmannae) is a large grazer that dwells in the mountains of coastal Namibia and southern Angola, occupying a distinct habitat that is not shared with its close relative, the Cape Mountain Zebra (Equus zebra zebra) in the Southern Cape. Nearing a population size of 13,000, the Hartmann’s Zebra roams along mountain escarpments, slopes, and plateaus 2,000 meters above sea level during the hot summer months and migrates to lower savannah landscapes during winter.

The Hartmann's zebra is the Iconic Species of the Southwest African Coastal Drylands Bioregion (AT10)

Equal in appearance

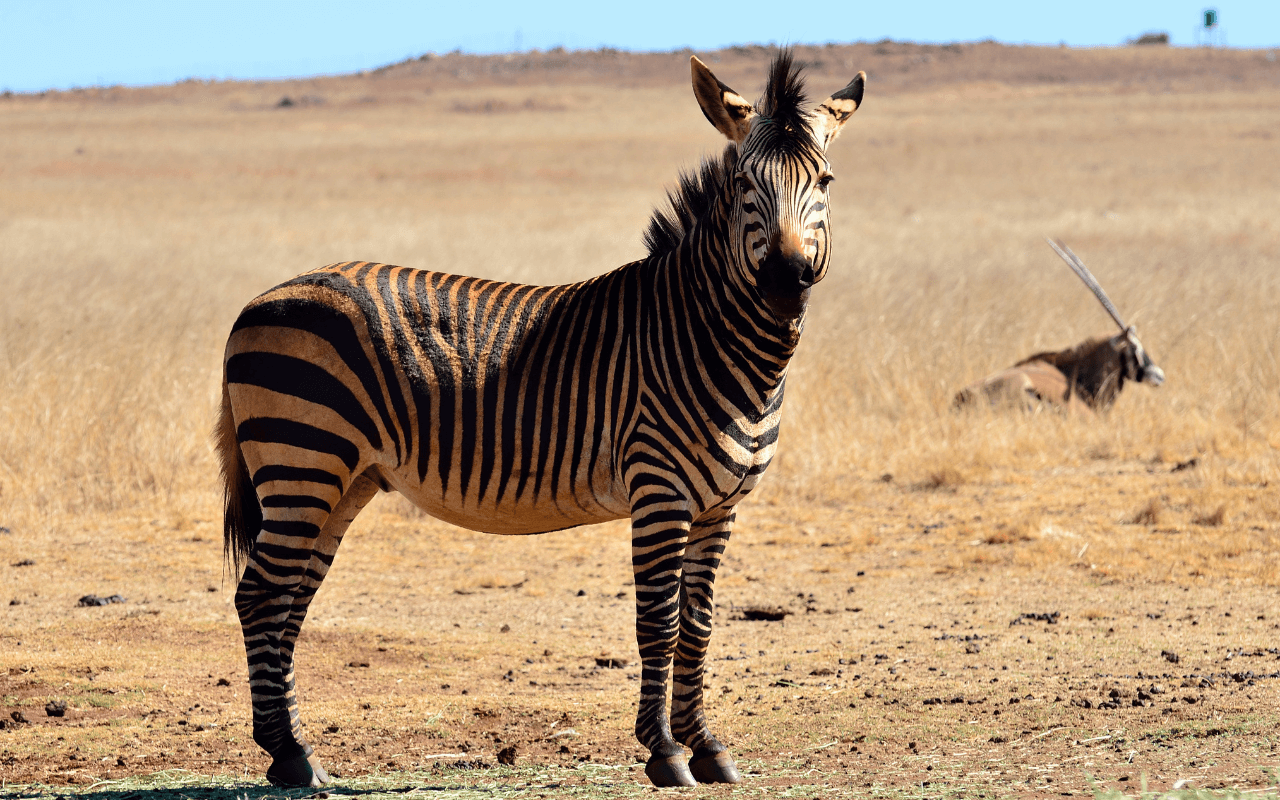

Adult males and females (stallions and mares) are indistinguishable, both in size and appearance. Stallions are slightly heavier, weighing an average of 298 kg, while mares are about thirty kilos less. They measure 1.5m at the shoulders and the length of ears 280 mm long, and the tail 500 mm long. Their stripes are comparingly lighter and wider than those of the Cape Mountain Zebra, but within the species, stripes have no outstanding difference between sexes.

.png)

Hartmann's mountain zebra. Image credit: Creative Commons, EcoPic

Peaceful Herbivores

The Mountain Zebra’s diet is based on tufted grass, bark, leaves, fruit, and roots from the Savannah vegetation. They graze along the contours of the terrain, and the grazing progression is in a zig-zag pattern. They are very resilient in high temperatures but prefer places where water flows, although they can dig for water in the ground. Their hooves grow extremely fast to be able to follow adults along the sometimes-steep slopes.

Mountain Zebras live in herds of two kinds: breeding herds and bachelor herds. Breeding herds are typically comprised of one stallion and up to five mares and their young, while bachelor herds have a social hierarchy with up to thirty individuals, respecting each of their roles and with no need for infighting. The average life span of a Mountain Zebra in the wild is 20 years old, although they can live almost a decade more. With a gestation of 12 months, mares give birth to a foal every 1 to 3 years, and their fertile age extends up to near the end of their lives. The mother will tend to the foal until it is one year old, and if it is a male, she will force him out of the group when a new foal is born.

Hartmann's mountain zebra. Image credit: Creative Commons, Mital Bhadaniya

A fable on the zebra

The Zebra and the San Peoples have coexisted in the Southeast African landscape for as long as they can remember, which is as far back as the earliest memory of humankind. The San claim to be among the most ancient people walking on Earth, so no other explanation of how Zebras got their stripes would be more legitimate than that provided in a fable now shared by Chigri-in-Africa, a ranger of the San Clan:

Long ago, when animals were still new in Africa, the weather was very hot, and what little water there was remained in a few pools and pans. One of these remaining water pools was guarded by a boisterous baboon, who claimed he was the 'lord of the water' and forbade anyone from drinking at his pool. One fine day when a zebra and his son came down to have a drink of water, the baboon, who was sitting by his fire next to the waterhole, jumped up and barked in a loud voice,

“Go away, intruders. This is my pool and I am the lord of the water.”

“The water is for everyone, not just for you, monkey-face,” the zebra's son shouted back.

“If you want some of the water, you must fight for it,” returned the baboon in a fine fury, and in a moment, the two were locked in combat.

.jpg)

Back and forth, they went fighting, raising a huge cloud of dust, until with a mighty kick, the zebra sent the baboon flying high up among the rocks of the cliff behind them. The baboon landed with a smack on his seat, taking all the hair clean off, and to this very day, he still carries the bare patch where he landed.

The tired and bruised young zebra, not looking where he was going, staggered back through the baboon's fire, which scorched him, leaving black burn stripes across his white fur.

The shock of being burned sent the zebra galloping away to the savannah plains and escarpments, where he has stayed ever since.

The baboon and his family, however, remain high up among the rocks where they bark defiance at all strangers, and when they walk around, they still hold up their tails to ease the sore rock burn of their bald patched bottoms.

The San people have held a long recent history of struggle to achieve self-determination by demanding their territories and ways of living be recognized by law through some legal representatives. Their connection to the semi-arid sandy savannah of the Kalahari Desert goes back in direct lineage to 150,000 years ago. They are among the most resilient people on Earth as they come from a line of ancestors who used to freely range the coastline to fish and inland to gather plants, trap small animals, and hunt larger ones. Today they try to stay close to the land and their ways by adopting a pastoralist or herding way of life by keeping cattle such as goats, donkeys, and cattle.

Interested in learning more about the bioregions of the Afrotropics? Use One Earth's interactive Navigator to explore bioregions around the world.

Launch Bioregion Navigator.jpg?auto=compress%2Cformat&w=1440)