The magnificent Arctic muskox: Ice Age survivor

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Iconic Species

- Wildlife

- Mammals

- Greenland

- Subarctic America Realm

One Earth’s “Species of the Week” series highlights an iconic species that represents the unique biogeography of each of the 185 bioregions of the Earth.

The muskox (Ovibos moschatus) would be better known by its Iñupiaq name: Umingmak, “The bearded one,” for it has no musk and is not an ox but a member of the goat/antelope family.

Yet myths persist, and most people remain unaware of these Ice Age relics who once roamed alongside mastodons, for muskoxen are the least studied animals in North America - due mainly to the remote, inaccessible, and often harsh Arctic environments in which they are found.

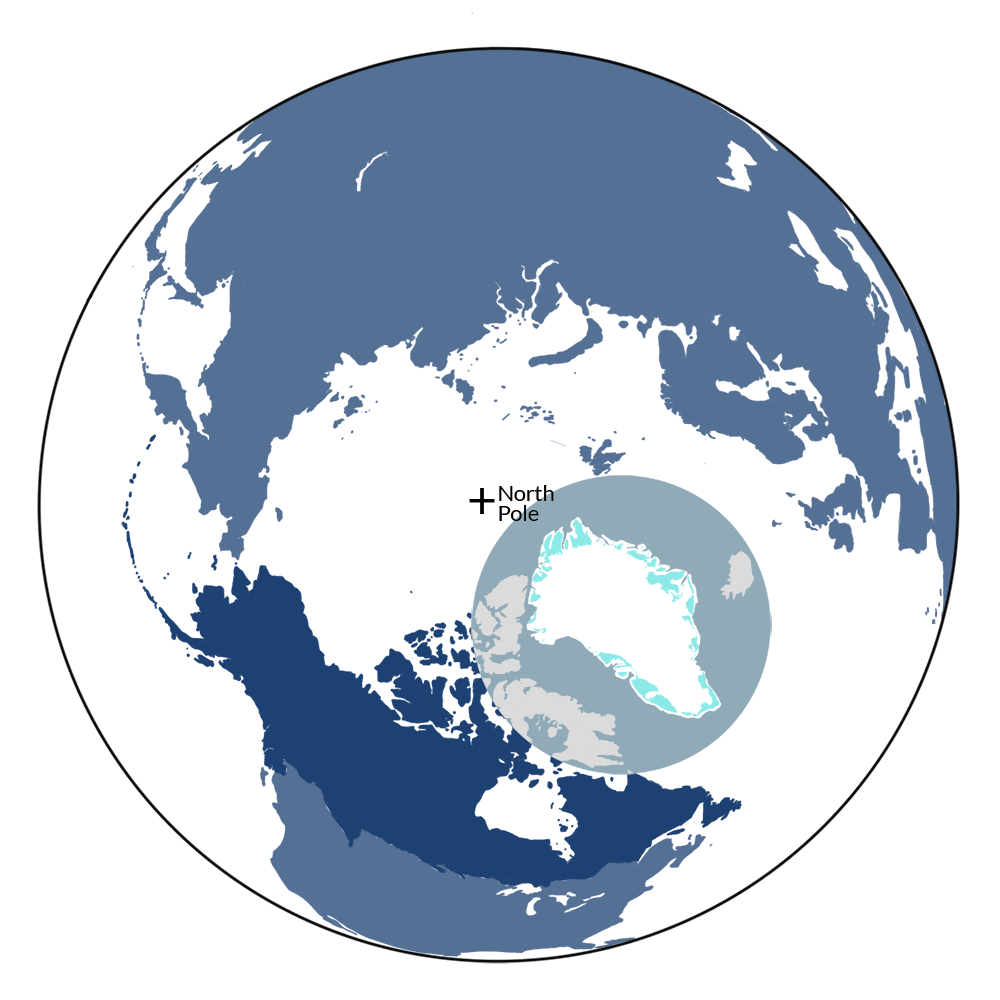

The muskox is the iconic species of the Greenland bioregion (NA1) located in the Subarctic America realm.

The ancient range of the muskox from Asia to the Arctic

The earliest evidence of muskox ancestry is found in Central Asia during the Late Miocene - Early Pliocene periods millions of years ago. Modern-day muskoxen are among the few survivors of the mass extinction of Earth’s megafauna that occurred during the Pleistocene, or Ice Age, due partly to a changing climate but mainly to the advancement of opportunistic human hunters into new regions across the Earth.

From Asia, muskoxen spread east through northern Europe and west across the entire Arctic Circle, grazing its grasses, willows, and sedges across the Bering Sea Land Bridge from Siberia into Alaska as early as 200,000 years ago. From there, these shaggy ruminants wandered across the Arctic Archipelago and mainland tundra of Canada and on into Greenland, where there remains a thriving population.

Considering their wide circumpolar range, it’s curious that among all the world’s animals, muskoxen are second only to the cat-sized foxes of California’s Channel Islands in their lack of genetic diversity.

Yearling muskox (Ovibos moschatus) standing in the winter snow at sunset. Image credit: Kjekol via Envato Elements

Significance to Indigenous Peoples of the Far North

The Greenland Inuit once believed that their people were descended from the “bearded ones.” Canada’s Naskapi revered them as examples of wise leadership, and the Cree used their imposing heads and horns in sacred ceremonies.

For thousands of years, muskoxen have been of vital nutritional and sociocultural importance to Indigenous peoples. The Inuit used their skins for bedding, tenting, and sled runners. In the absence of wood, muskox bones and horns were used for ladles, sealing harpoons, bows and arrow points, crossbars for sleds, and other specialized tools necessary for subsistence life.

Muskoxen themselves were revered for their example of the ability to endure and even thrive amidst harsh conditions through the strength of their close communities.

The decline of muskoxen: A tale of overhunting and loss

Due to overhunting, muskoxen eventually vanished from many northern regions. In prehistoric times, they were extirpated in Eurasia, where only their images in the paintings and sculptures of Paleolithic caves remain. As happened across their entire range, hunters would kill all the muskoxen they could find, as conservation was not a consideration for people whose primary concern was near-term survival.

The muskox herd’s natural defense is to stand and face its predators, forming a protective circle around its young calves with the adults’ formidable horns facing outwards. While effective against wolves, this strategy made it easy for hunters with rifles to kill the entire herd at once.

Across the North, commercial whalers and sealers, explorers, and local hunters killed muskoxen by the thousands for meat and dog food, and to support fur farming and remote weather and trading outposts.

In the late 1850s, Native Alaskans reported killing a herd of 13, thought to be the last muskoxen in the state until their reintroduction from Greenland in the 1930s.

Following the “Great Slaughter” of tens of millions of buffalo across the American West in the late 19th century, market hunters turned their attention north to hunt muskoxen for their hides, with the Hudson’s Bay Company alone recording the killing of more than 23,000. With only 400 muskoxen remaining, fears about their possible extinction resulted in the introduction of Canadian regulations in the early 1900s.

Sociable, speedy giants of the North

Muskoxen are intelligent, gregarious animals who generally live in groups of a few dozen animals and have a lifespan of between 12 and 20 years. These herds are sometimes led by a single female, accompanied by bulls who have fought hard for the privilege of breeding and providing essential herd defense while their male rivals become solitary wanderers.

Their imposing appearance belies their weight and speed, for even the bulls, who stand 1.5 meters (5 ft) tall at the shoulders, rarely exceed 227 kilograms (900 lbs) in the wild, and they can run an agile 60 kilometers per hour (37mph) across the tundra hummocks.

A herd of muskoxen withstanding the frigid winter as one. Image credit: Wirestock via Envato Elements

Adaptations for survival in the tundra

Muskoxen are remarkably resilient, as their physiology evolved to survive in some of the coldest regions on Earth, where they thrive at -20°C (-4° F). They are heterothermic, which refers to the ability to shut off thermal regulation in some parts of the body to reduce heat loss.

This combines with the unique advantage of having hemoglobin which is far less sensitive to cold than that of most mammals. In winter, muskoxen’s long, dark outer guard hairs cover a layer of underwool called qiviut, which is eight times warmer than sheep’s wool and finer and softer than cashmere. (Calves are born already wearing this cozy coat.)

Shedding naturally each spring, qiviut provides a valuable, promising resource for a new Arctic economy, and the feasibility of muskox domestication for this purpose has been well-established over the past 70 years as they adapt well to kind, regular handling.

Important role in maintaining carbon sinks & biodiversity

The presence of large herbivores such as muskoxen and caribou is crucial to regulating and maintaining healthy Arctic grasslands as a carbon sink. Early studies indicate that the absence of grazing, trampling, and fertilizing results in a radical change in ground cover associated with an increase in the release of carbon dioxide and methane.

The disappearance of the rare, diverse native plants that naturally predominate (such as the grass-like graminoids with their tiny, delicate flowers) alters the integrity of tundra vegetation and its ecosystem function, which includes providing nutrients, trace minerals and pollen vital to Arctic fauna. These plants provide habitat and resources for many species of birds, insects, and small herbivores such as arctic hare and lemmings - which in turn feed carnivores such as arctic foxes and wolves. The decline of muskoxen and caribou may thus amplify the effects of climate change on Arctic biodiversity.

A mother muskox and this year's calf. Image credit: Dration via Flickr

Losing life and habitats due to the climate crisis

According to wildlife researchers and Indigenous observers, many muskox populations are in dramatic decline due to the climate crisis, which is causing severely fluctuating winter precipitation, including deeper snow, extreme ice tidal surges, and rain-on-snow events that form impenetrable ice sheets over winter grazing.

Lack of access to nutritious browse has led to starvation, and its scarcity has affected the health of cows during gestation, resulting in low calf survival rates. In the last 30 years, increasing predation by grizzly bears has also been taking a serious toll. Mass die-offs of muskoxen are occurring with greater frequency, caused additionally by the northward movement of deadly parasites and bacteria to which muskoxen are increasingly vulnerable.

Muskoxen are also adversely affected by pollution and habitat loss due to the increase of mining and fossil fuel extraction in the Arctic. Like whales, they are extremely sensitive to seismic activity that fragments their territories. They keep their distance miles away, often far from riparian zones on which they would normally rely for better foraging and snow conditions.

Muskox in an autumn landscape in the Arctic Tundra. Image credit: Galyna Andrushko via Envato Elements

The urgent need for further study and recognition

While the muskox has recovered in different regions due to international efforts to regulate hunting in the last century, enforcement has been inadequate, and excessive hunting remains a serious threat. Their global population status is unknown, as no comprehensive count has been completed to guide international management strategies. Satellite data collection, which is later verified and continued on the ground by Indigenous researchers, offers a promising solution.

With the Arctic warming at four times the world average, further studies are urgently needed to determine the true demographic and health status of muskoxen and how their decline may be impacting other wildlife and plants that are reliant on the ecosystem balance their presence provides.

Let’s hope that we come to recognize the deep significance of these Ice Age survivors to the increasingly fragile web of Arctic life before it is too late, and before people have even become aware of a unique and magnificent large mammal that has endured through millennia.

Explore More Iconic Species