What is a wolverine? Meet a keystone predator of the North

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Mammal Assemblages

- Ecosystem Restoration

- Species Rewilding

- Iconic Species

- Mammals

- Wildlife

- Subarctic Eurasia Realm

- Siberia & East Boreal Forests

One Earth’s “Species of the Week” series highlights an iconic species that represents the unique biogeography of each of the 185 bioregions of the Earth.

High in the snow-covered mountains, a shadow slips across the tundra. This is the wolverine: powerful, elusive, and vital to the health of northern ecosystems.

The wolverine has earned mythic status in both science and storytelling. But behind the legend is a very real animal whose survival is deeply tied to the future of cold-climate habitats and the snow they depend on.

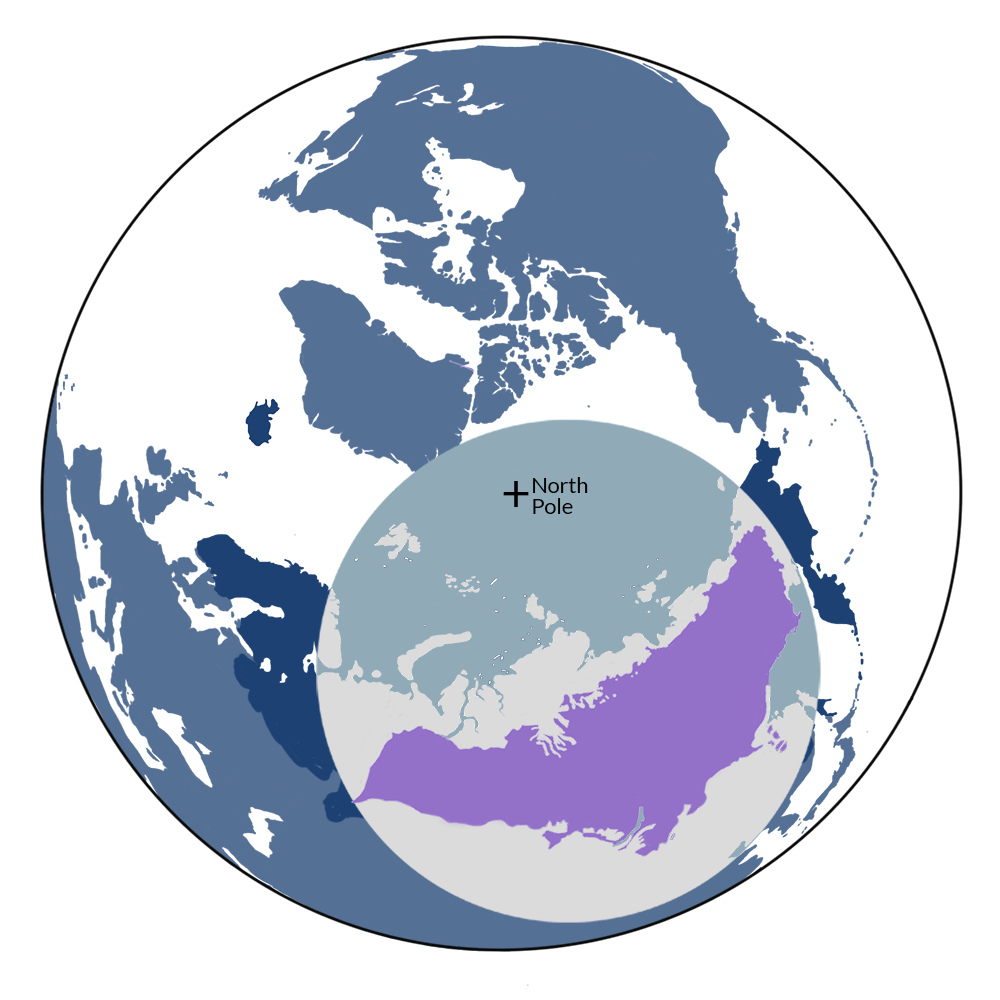

The wolverine is the iconic species of the Siberian Boreal Forests & Mountain Tundra bioregion (PA7), located in the Siberia & East Boreal Forests subrealm of Subarctic Eurasia.

Life in the cold: The wolverine’s wild northern terrain

Wolverines (Gulo gulo) inhabit some of the harshest environments on Earth, including remote boreal forests, alpine tundras, and subarctic regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

They are most commonly found in the taiga of Siberia and Fennoscandia, as well as the mountainous wilderness of Alaska and Canada. While they once roamed much farther south in both North America and Europe, they are now largely restricted to areas with deep snow and minimal human activity.

Built for survival through strength and specialized features

With a build resembling a small bear crossed with a badger, the wolverine is a muscular mammal built for endurance. It has a broad head, powerful limbs, and crampon-like claws that help it scale snow-covered cliffs and trees with ease.

Males can weigh up to 18 kilograms (40 lb), with females slightly smaller, yet both are strong enough to take down prey several times their size. Their dark, frost-resistant fur helps them survive freezing temperatures, and their rotated molars are uniquely adapted to rip flesh from frozen carcasses.

With wide, snowshoe-like paws, the wolverine can move easily across deep snow, staying on top of the pack where other animals might sink. Image credit: © Slowmotiongli | Dreamstime

A carnivore with a wide-ranging diet

Despite their reputation for gluttony, wolverines are resourceful scavengers and opportunistic hunters. In winter, they rely heavily on carrion, often from wolf or lynx kills.

They are also known to take down live prey, ranging from small rodents to full-grown deer, particularly those weakened by snow or hunger. Their diet includes porcupines, squirrels, rabbits, beavers, and even moose.

When food is abundant, they cache meat for later, a critical behavior for nursing females during the lean winter months.

Their role in maintaining ecosystem balance

Wolverines serve as both scavengers and predators, helping to clean up carrion and regulate populations of smaller mammals. They often follow predators like wolves and lynx to scavenge remains, contributing to nutrient cycling in their ecosystems.

By competing with other carnivores and influencing prey behavior, wolverines help maintain balance across food webs in cold-climate biomes.

Wolverine paw prints in the snow. Image Credit: © Okyela, Dreamstime.

Solitary yet far-ranging hunters with complex behaviors

Wolverines are mostly solitary and roam vast territories. A male may cover more than 600 square kilometers, while females occupy smaller but still expansive ranges.

Despite their independence, some males form long-term bonds with multiple females and may reunite with their offspring during certain seasons. They are known for their boldness, sometimes challenging bears or wolves for food.

Reproduction timed to the snow

Mating occurs in summer, but females delay embryo implantation until winter. This ensures that kits are born in early spring when conditions are more favorable.

Females give birth in snow dens, where two or three kits are raised until weaning in mid-May. These dens depend on deep, persistent snow, which is increasingly threatened by climate change. Kits grow quickly and may reconnect with their fathers later in the year, traveling together before becoming fully independent.

The cover of Kuekuatsheu Creates the World by Annie Picard, a modern retelling of the Innu creation story featuring the wolverine. Image credit: Running the Goat Books.

Sacred and storied in Indigenous cultures

For many Indigenous peoples across the northern forests and tundra, the wolverine holds deep cultural significance. Among the Innu of eastern Quebec and Labrador, the wolverine is known as Kuekuatsheu, who played a central role in the creation of the world. In one story, after a great flood covers the land, Kuekuatsheu sends a mink to dive into the depths to retrieve mud and stones. With these, he forms the first island, giving rise to the world as it is known today.

Other Indigenous groups across the boreal and subarctic regions also feature the wolverine in their oral traditions. Among the Mi’kmaq and Passamaquoddy, the wolverine appears as Lox, a cunning and unpredictable trickster who often travels with the wolf and causes mischief.

Among the Dené peoples of northwestern Canada, the wolverine is seen as a disrupter, bringing change through bold action. This role is similar to that of coyote in the Southwest or raven among the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Coast. These traditions speak to the wolverine’s deeper meaning as a symbol of survival, resilience, and transformation.

Warming winters and shrinking ranges

Globally, the wolverine is listed as Least Concern, but that status masks a more troubling reality. The species has disappeared from much of its former range due to habitat loss, trapping, and fragmentation.

Its dependance on deep spring snow to raise young makes it highly vulnerable to climate change. As warming temperatures reduce snowpack, the number of viable breeding sites declines. In response, the United States recently listed the wolverine as a threatened species in the Lower 48 states.

A wild wolverine in Lieksa, Finland. Image credit: © Esa Lähteenmäki | Dreamstime

Rewilding wolverines to restore ecosystems

A 2024 study funded by One Earth and led by RESOLVE identified the wolverine as one of 20 large mammals that could help restore ecosystem integrity across vast landscapes. Their presence can shape vegetation, influence prey behavior, and even improve soil health.

The research found that reintroducing wolverines, alongside species like black bears and bison, across 60 North American ecoregions could help regenerate over 3.2 million square kilometers of land.

Charting a path forward

While populations remain stable in parts of Canada and Scandinavia, many regions are working to bring wolverines back. In Colorado, reintroduction plans are underway, and sightings have returned to places like Utah and California.

Each confirmed presence signals hope, not just for the species, but for the habitats they support. Conservationists believe that protecting and rewilding wolverines is not only possible, but essential to restoring the health of northern ecosystems.

Support Nature Conservation

.jpg?auto=compress%2Cformat&h=600&w=600)