Why the Baird's tapir is known as a 'living fossil'

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Mammals

- Iconic Species

- Upper South America

- Southern America Realm

The Baird's tapir, or Central American tapir, known as Danta among the Colombian people and Tizimin among the Maya in Southern Mexico, is a remarkable creature that seems to defy time. Named in honor of the American naturalist Spencer Fullerton Baird (Tapirus bairdii), this species presents a fascinating case of evolutionary stasis.

When its bone structure is compared to that of a fossil tapir from the Eocene Epoch, the similarities are remarkable, earning it the title of a 'living fossil.' This suggests that the ecological conditions of its habitat, including natural predators, have remained relatively stable for some 35 million years.

The tapir is part of the Perissodactyla order, distinguished by an odd number of toes. Unlike other members, Baird's tapirs have retained four toes on their front feet and three on their hind feet, leaving a distinctive footprint in their wake. This adaptation makes each toe broader and stronger, effectively supporting the animal's weight.

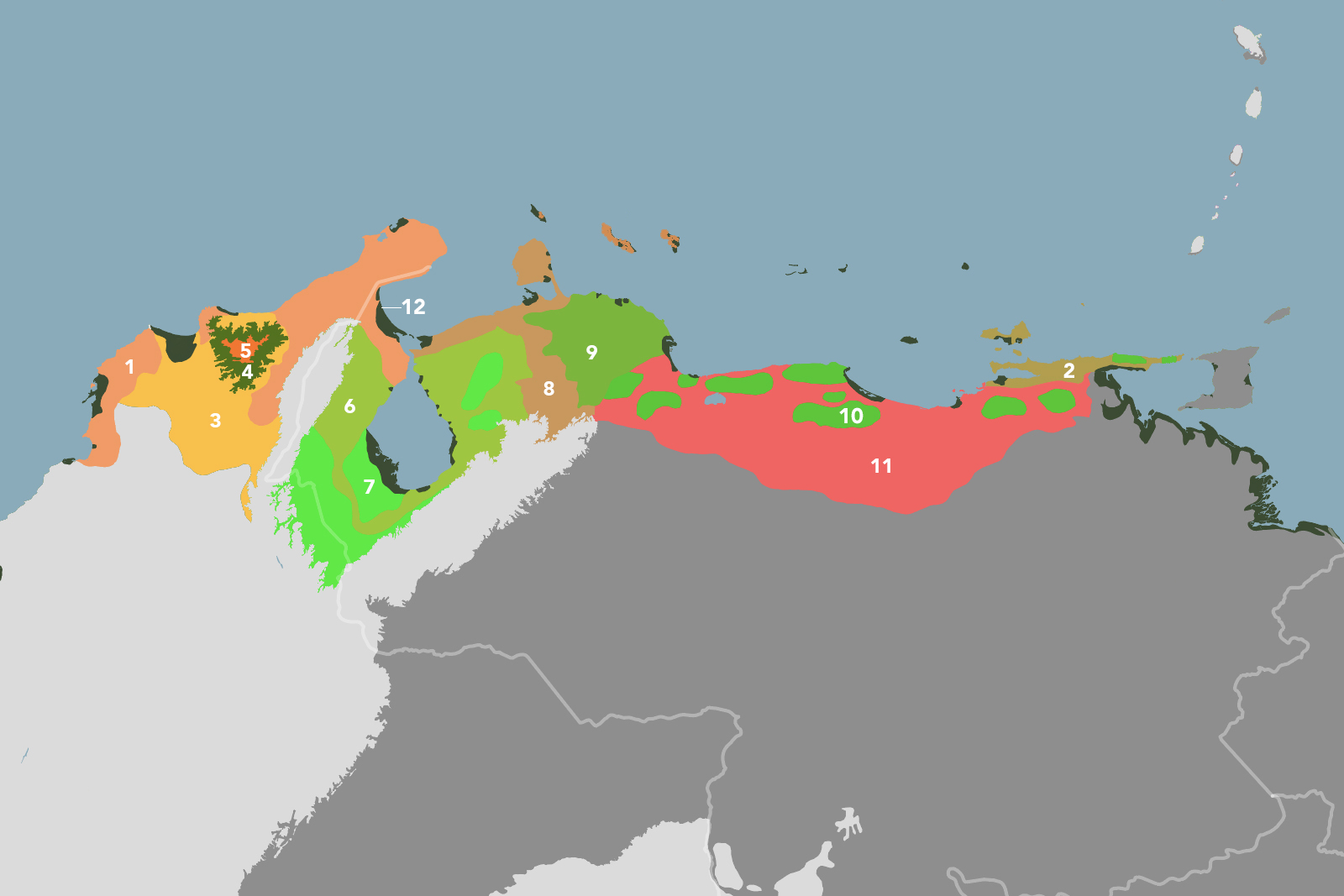

The Baird's tapir (Tapirus bairdii) is the iconic species of the Venezuelan Coast bioregion (NT23) located in the Upper South America Subrealm.

Physical characteristics and habitat

Weighing up to 300 kilograms (661.39 pounds) and measuring about 1.5 meters in length, the Baird's tapirs' physical appearance can be deceiving. At a distance, it might be confused with the lowland tapir, given their similar brown short coats. However, the Central American variant lacks the mane or crest of its lowland cousin and boasts a thick, tough hide, particularly on its hindquarters.

A notable feature is its horse-shaped head with a prolonged snout, or proboscis, which proves incredibly useful for swimming and sensing smells, alerting the tapir to predators or danger. Despite their poor eyesight, their acute sense of smell and hearing keep them well aware of their surroundings.

Baird's tapir. Image credit: Brian Gratwicke, Flickr, CC by 2.0

Reproduction and lifespan

The reproductive habits of the Baird's tapir, especially in the wild, remain enigmatic. Observations in captivity reveal a gestation period ranging between 390 and 400 days, with the birth of a single calf weighing about 10 kilograms (22 pounds). The calf, nicknamed 'watermelon' for its patterned coat and body shape, is quick to start walking and exploring with its mother shortly after birth. These calves stay with their mothers for up to two years and reach maturity between three to five years, living as long as twenty-two years in the wild.

Primarily solitary creatures, tapirs occasionally form associations for breeding without evidence of males establishing exclusive territories. They communicate through visual and auditory signals, including loud sounds, to assert dominance over territory, especially during dusk and nighttime activities.

Preferring tropical rainforests, cloud forests, and flooded grasslands, the Baird's tapir is an adept swimmer. This skill likely contributed to its spread across Central America, from southeastern Mexico to Colombia's Darien bioregion. Despite historical continuity in its range, modern threats have restricted it to protected areas and community-held lands.

Baird's tapir. Image credit: Courtesy of Bernard Dupont, Flickr.

Conservation efforts and challenges

Despite being the largest land mammal in Central America, the tapir faces numerous threats from habitat destruction due to agricultural expansion and tourist developments. Protected areas in Mexico, such as Calakmul and Sian Ka'an, provide crucial sanctuaries. However, these, too, face challenges from human encroachment. Community involvement in conservation, mainly through sustainable practices like agroforestry, offers hope for the tapir's future.

The story of the Baird's tapir is a poignant reminder of our shared responsibility to protect these ancient creatures and their habitats. By supporting conservation efforts and advocating for sustainable development, we can ensure that this living fossil continues to thrive for generations to come.

Explore Earth's Bioregions

_CC-Bernard%20Dupont-2013_resized.jpg?auto=compress%2Cformat&h=600&w=600)